CCRI research seeking to unlock mysteries of pancreatic cancer with $1.8M NCI grant

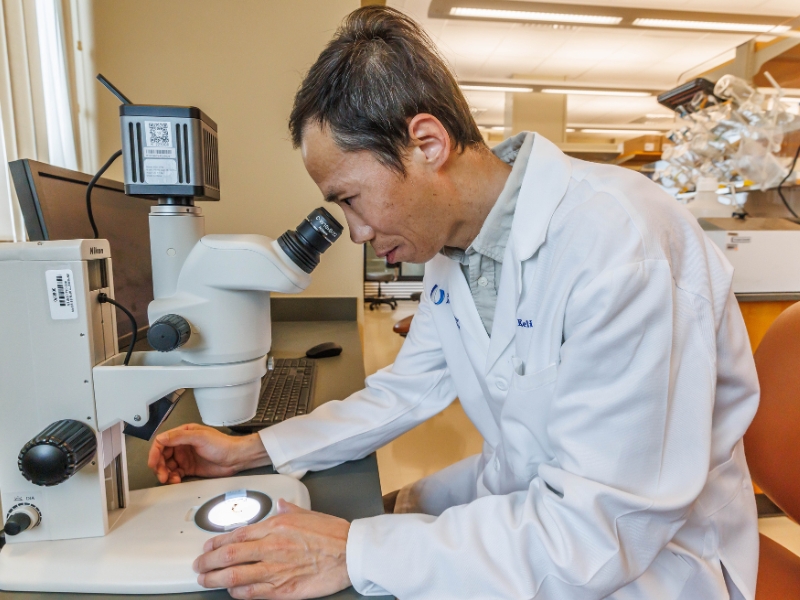

Inside the labs at the Cancer Center and Research Institute at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, researchers are studying how a protein that’s been in humans since the embryonic stage plays a role in triggering the development of a particularly deadly type of pancreatic cancer.

The project, in the second year of a five-year $1.8 million grant from the National Cancer Institute, could lead to better biomarkers for the disease and improved treatment, said Dr. Keli Xu, associate professor of cell and molecular biology and a CCRI member. Research funded by the grant that notes the cell of origin for a type of pancreatic cancer was published in the journal Oncogene.

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) makes up more than 90% of pancreatic cancers. Although it is the 10th most common malignancy, PDAC is the third leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States. The survival rate for PDAC is low because it is difficult to detect in its early stages and resists many current treatments.

Learning more about how PDAC starts can lead to a greater understanding of how it can be treated more effectively, Xu said.

“Our goal is to identify the molecular mechanisms that drive PDAC from its earliest stages so we can intervene before the disease becomes aggressive and difficult to treat,” he said.

The study’s findings suggest that cells expressing lunatic fringe protein may serve as a cell of origin for PDAC.

Lunatic fringe protein (Lfng) is encoded by the Lfng gene and plays a key role in an embryo’s development. In the embryonic stage, Lfng sets the anterior boundaries of the cells that eventually form vertebrae, ribs and the dermis, or middle layer of skin. During adulthood, Lfng continues to be expressed in parts of the body including the pancreas.

The CCRI research suggests that high Lfng expression is associated with poor survival in PDAC patients.

Think of it like a car with the potential to speed out of control. The growth-boosting gene Kras is like a jammed accelerator pedal that forces the car to run too fast. P53 is the braking system, but it may be damaged or missing. Lfng acts like a turbocharger, working best when connected to the signaling protein Notch3.

When the brakes (p53) fail and the engine (Kras) is revved up, the car is already dangerous. Add the connection of Lfng and Notch3, and cancer development is speeding ahead.

Researchers at UMMC found that removing Lfng in these cells can slow or reduce pancreatic tumor formation. They also discovered that blocking Notch3 signaling may help stop PDAC from spreading, pointing to possible new treatment approaches.

“Our findings suggest that, in more aggressive cases of pancreatic cancer that are resistant to chemotherapy, treatment with gamma secretase inhibitors could turn off the Notch3 signaling and inhibit cancer growth,” Xu said.

Conventional approaches such as surgery, radiation and chemotherapy have shown limited success in fighting this form of pancreatic cancer, but research suggests that combining targeted therapy with existing treatments could offer better outcomes.

“By understanding how PDAC starts at the cellular level, we can design therapies that stop it before it spreads,” Xu said. “This work could help us identify better biomarkers for early detection and develop drugs that specifically target the pathways driving tumor growth.”

Dr. Ajay Singh, professor of cell and molecular biology and CCRI associate director of basic and translational research, said Xu’s findings are significant.

“His research is providing new insights into this lethal disease and has the potential to pave the way for targeted therapies and early detection strategies,” he said.

Xu, a cancer researcher at UMMC and a CCRI member for the past 14 years, holds a PhD in biochemistry from Rutgers University and was a postdoctoral fellow in developmental biology and cancer biology in the developmental and stem-cell biology program at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada. He earned degrees in biochemistry and molecular biology from China’s Nanjing University and Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry, respectively.

The role of proteins such as lunatic fringe in embryonic development and, later in life, in the development and spread of cancer led Xu from developmental biology to cancer research.

“What makes this research so fascinating is that it began with developmental biology. The proteins that are needed in development can also play a role later in life in the development of or suppression of cancer,” he said, noting that while high levels of Lfng can be a start to PDAC, it has been shown to suppress types of breast cancer.

The NCI grant is allowing Xu’s team to continue dissecting the interactions among Lfng, Notch3, and other key signaling pathways involved in PDAC initiation and progression. The goal is to translate these discoveries into new diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies that improve survival for pancreatic cancer patients.

“Pancreatic cancer research has been challenging, but we’re at a turning point,” Xu said. “Research is bringing us closer to learning how this cancer starts and how we can stop it.”