An extraordinary admission: 50 years ago, Mississippi native perseveres to become medical school’s first Black graduate

Note: This article was originally published in the Winter 2022 issue of Mississippi Medicine, the medical alumni magazine.

Of course, they said he was crazy.

Back then in the 1950s when a young James Oliver let it be known that he wanted to be a doctor; back then when there weren’t even any black doctors on TV, much less in his hometown of Hernando; back then in Mississippi.

“One of the guys in the neighborhood said, ‘When you told us that, we all thought you were crazy,’” Dr. James Oliver, now 80, recalls some 70 years later. “In Mississippi, things were not very good for black people in the 1950s.”

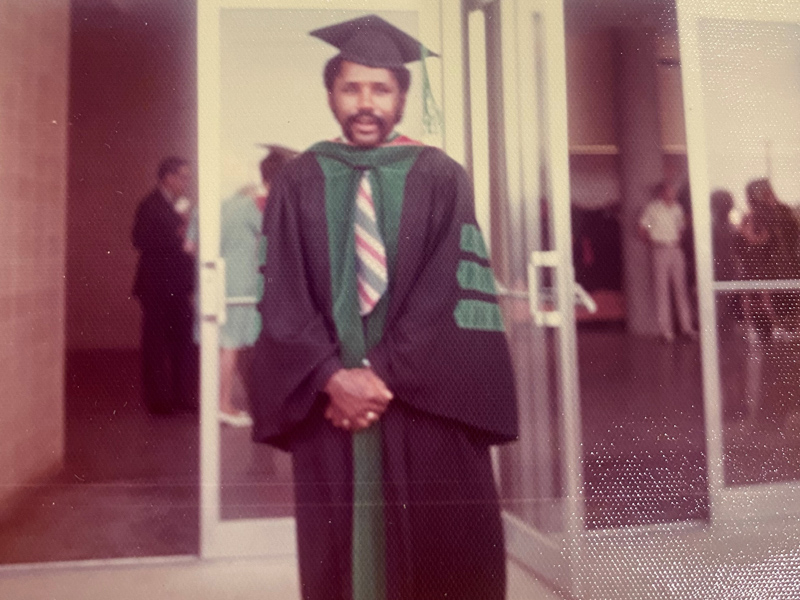

Neither were they very good in 1968, the year Oliver entered medical school; they weren’t much better in 1972, the year he became the first African American to earn a medical degree at UMMC; despite that, he had fulfilled the promise he made to himself and to anyone who would give him a chance.

“Your only limitation is your imagination,” said the retired cardiologist, speaking from his home in Chesapeake Beach, Maryland. “When I was young, I imagined I could change the world.”

Fifty years ago, James Oliver did change the world, or at least the part of the world occupied by the School of Medicine. Elsewhere, others were changing the world too, but not always for the better.

The year Oliver entered the School of Medicine, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis. The year he graduated saw the end of “The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male;” but it had lasted 40 years.

At the end of an era when African American men had been treated as medical guinea pigs in Alabama, Oliver became a medical doctor next-door in Mississippi. He was the third black student to enter the School of Medicine, the first to finish, and the only one in the Class of 1972.

‘You won't believe it…’

For Essie Mae Sandridge, the arithmetic of life was harsh: one parent plus seven children equaled two jobs.

To better take care of her children, she held down a couple of jobs at a time. One was working as a domestic for the Army doctor in Hernando. Some seven years after James Oliver was born, in 1941, he decided he wanted to be like that man.

“I saw how the doctor my mother worked for lived,” Oliver recalled, “and I saw how we lived, and I decided I wanted to live the way he lived. And the way to do that was to be a doctor.”

That’s one family story. The other one says Oliver wanted to be a doctor so he could take care of his grandmother, Lela Sandridge.

“My mother was divorced and moved in with her mother and worked. So my grandmother stayed home, fed us breakfast, fixed us an after-school snack and fed us dinner,” Oliver said.

“My grandmother was more like a mother to us, but she was ill a lot. I wanted to become a doctor so I could help her. She thought that was a good idea, and she encouraged me with some good advice and her social security check to pay for my college tuition.

“She had always told me, ‘Somebody might be smarter than you,” Oliver said, “but don’t let them outwork you.” So Oliver did not.

To make money to pay for college, he worked in construction and some odd jobs during the summer. Nor did he let anyone outwork him when it came to playing the trumpet. He blew his trumpet all the way to Mississippi Vocational College in Itta Bena, now Mississippi Valley State University, which awarded him a music scholarship.

Neither did he let the other biology majors outwork him at MVC, although a few may have out-earned him: At one point, he didn’t have enough money for soap, so his roommate broke a bar in two and gave him half.

He graduated, clean-washed and eager, in 1963, set on living the doctor’s life. But that would have to wait.

“It wasn’t easy getting into medical school after graduating from a non-accredited college,” Oliver said. At the time, his alma mater wasn’t accredited outside the state of Mississippi, he said. And the School of Medicine at UMMC wouldn’t enroll its first African American student for three more years.

Oliver had sent his application to three other medical schools – at Howard University in Washington, D.C.; Meharry Medical College in Nashville and Georgetown University, also in the nation’s capital, and one of the country’s top-ranked universities then and now. He got one interview.

“You won’t believe it,” he said. “I got the interview at Georgetown. The interviewer told me, ‘The only reason I agreed to see you is because, in all the years I’ve looked at applications for medical school, you were the first person who said he finished lower in his class than he actually did.’”

In an act of self-deflation he can’t explain, Oliver’s application demoted him to seventh, instead of sixth, in his class. Reflecting on this in hindsight, it probably wouldn’t have mattered if he had finished first, he said.

“The interviewer also said he thought I wouldn’t be able to keep up at Georgetown.”

‘If you admit me…’

Turned down by the Hoyas, Oliver pursued his path to medical school the way a running back seeks daylight on the football field.

“You have to go north or south in order to score,” he said, “but there are times when you have to go east or west, until you can turn up the field toward your goal.”

Oliver zigged up to Ohio, took more science courses at the University of Dayton, then worked in Miamisburg as a technician for a Monsanto lab.

Then he zagged into the Army, winding up eventually as a researcher at the now-defunct U.S. Army Biological Warfare Laboratories in Fort Detrick, Maryland.

But all that time, during all those crab-walking detours, he knew he was going to going to score. At night he took graduate courses at the National Institutes of Health and studied to prepare for the MCAT. He was still in the Army when he applied to medical school and headed back up field.

“I was not going to let anything stand in my way of going to medical school and becoming a physician,” he said. “I had never failed at anything academically, and I didn’t think I would fail at that. My feeling was: If you admit me, I will graduate.”

On Aug. 30, 1968, Oliver, who was granted an early out for going back to school, was discharged from the military. “I started school nine days later,” he said.

“My grandmother was ecstatic. She always called me ‘my boy.’ She told everyone my mother may have birthed me, but she was my mother, and I was her boy. Whenever her peers were around, they had to address me as ‘Dr. Oliver.’”

‘Be it bad, good or ugly…’

Oliver was back home in Mississippi, but there was a moment or two when he wondered why.

He could have gone to Penn State instead. “I had been accepted to the College of Medicine there,” he said. Located in Hershey, it was brand-new.

“But they gave only one test per semester,” Oliver said. “I didn’t want to put all my effort into one exam. Also, Hershey was lily white. I thought I would rather be segregated in Mississippi than isolated in Pennsylvania.

“I had lived in Mississippi from the time I was born until I graduated from college. Like most people, I had an allegiance to my birthplace, be it bad, good or ugly.

“So I came down to UMMC for an interview, and I asked to meet with a student of color, and met Carrie Paul Hunter, the second black student to be admitted to the medical school. And I found out that Sammie Long was the first. I believed I would come down there and be a support for them.

“Sammie had started in 1966. That first semester, we had our Thanksgiving holiday. Before we went back to class the following week, Sammie called me and said she wasn’t coming back; she couldn’t take it any longer. She dropped out.”

Long left UMMC for Meharry, where she would graduate. Hunter transferred to New York University. Before his first semester was over, Oliver was suddenly the school’s only black student, and he wasn’t leaving.

“I was older than Carrie and Sammie,” he said. “And I had been in the Army and had given my country two years, nine months and 11 days, which I volunteered for; and so I felt I deserved to be there.

“There were two or three incidents that were somewhat bothersome, but I don’t believe there was a collective effort to make me feel uncomfortable.”

Still, it was 1968. Relating a story he also recounted in “Promises Kept,” Janis Quinn’s history of the Medical Center, Oliver recalled an experiment in which his lab partner, waiving the use of a safety pipette, accidentally swallowed some of Oliver’s blood. When racial stereotypes fueled speculation about his white partner’s sudden transformation, Oliver bled prejudice of its power with a punchline of his own.

“I said, ‘It’s possible that the guy did find a beat-up Cadillac in front of his house, and it’s possible his wife did run off with the mailman, but I damn sure don’t believe he could ever dance like James Brown.’

“I don’t think anybody was cruel to me. I had good friends. Anyway, especially in medical school, you’re too busy to focus on being nasty to someone else.”

‘They killed those students…’

In 1968, Oliver was early into his first marriage; he and his wife at the time were bringing up their daughter, Tina – now Tina Powell of Fairfax, Virginia.

“I remember living in family housing at the time and I remember riding a tricycle,” Powell said. “And for some reason, I even have a vague recollection of my father graduating; I was 4 years old. I grew up being very proud that my father was a doctor.

“I knew about Jackie Robinson and some other trailblazers. When I found out my father was the first African American to graduate from the medical school, I realized, ‘Oh, my goodness, my father was one of those trailblazers.’”

But Powell was an adult before she realized what her father had overcome, she said, and she is documenting his story so her children and grandchildren will realize it, too.

“When his parents were in school, blacks in Mississippi weren’t allowed to go beyond the eighth grade. So by the time my father was in middle school, no one at home could help him with his school work; he had to do it all by himself.

“He and Prather Randall, one of his friends in Hernando, made a pact with each other that they were going to get out of that town and be a success,” she said. “Prather Randall, became a lawyer, and my father became a doctor.”

In the school where he would earn his medical degree, he was the sixth oldest in his class, he said; he believes the five oldest were also ex-military. “There was a kinship because of that,” he said.

Dr. Ralph Vance (’72) remembers Oliver well. “In medical school, we were happy to have him. He was very personable and easy to talk with,” said Vance, UMMC professor emeritus of oncology/hematology.

“He was a great individual, first, and then became a great doctor.”

Oliver was a member of “an extremely good class, an extremely good group of people,” said Dr. Joe Files (’72), another UMMC professor emeritus of oncology/hematology. “He was working hard like the rest of us, studying hard.”

A couple of decades ago, Dr. Bryan Barksdale (’72) was on a flight when he ran into Oliver on the plane. “He told me that he never felt any animosity, any racial tension in medical school. I don’t think our class would have tolerated it,” said Barksdale, UMMC professor of medicine, cardiology.

“Anyway, we were all so dang busy worried about medical school.”

For his part, Oliver worried back then that there weren’t more African Americans in the school. “We were told by the dean that they accepted more each year, but only one would show up,” he said.

This led to the formation of an ad hoc committee; with Oliver as a member, it put together a minority recruitment program. “The following year, four black students were enrolled,” he said.

Mostly, nothing Oliver heard or saw inside the Medical Center caused him to regret being there, he said. But outside the Medical Center, it was a different story.

“The only time that really made me question my decision was when they killed those students at Jackson State University,” he said.

It was May 1970, at the end of his second year. Law enforcement officers, all white, were responding to a student demonstration at JSU as a high school student named James Earl Green walked across the campus on his way home from work; he was on the side of the street opposite from the demonstration. The bullets the officers fired injured 12 people and killed two, including Green.

At UMMC, a fellow medical student told Oliver that as he was walking to class a day after the shooting, a police officer called out to him and said, ‘We’ll send you some more tonight.’”

To show solidarity with the black students protesting the shootings across town, Oliver asked his classmates to wear black armbands. “And I suspect, out of about 75 students, five or six showed up with armbands in class that morning,” he said.

Later, in another class, a tenured professor mounted the dais wearing a black armband, Oliver said; and afterward, more students joined him.

“That was probably the height of my career at UMMC.”

‘The biggest impact…’

For the last two years of her life, Lela Sandridge could say there was a doctor in the family. Dr. James Oliver was a second-year resident when his grandmother passed away.

Because of his hands, he had foregone a career as a surgeon. “I couldn’t tie my shoes until I was nine or 10,” he said.

Anyway, he was more interested in hearts. “Cardiovascular disease is the number cause of death in the U.S.,” Oliver said. “I thought I could make the biggest impact by becoming a cardiologist.”

To that end, he did a fellowship in cardiology at Boston City Hospital, abiding by a suggestion from his advisor, the late Dr. Herbert Langford, a renowned expert on hypertension at UMMC.

During the last year of his fellowship, while attending an American Heart Association meeting, he met the late Dr. Patrick Lehan, director of the Division of Cardiology and Cardiovascular Diseases at UMMC. At Lehan’s urging, Oliver applied for a cardiology opening at the VA Hospital in Jackson, but never heard back.

Later, he joined the faculty at Howard University; he remained in the D.C. area, where he saw patients in a private practice that lasted for decades. At Howard, he reconnected with an old friend, a hematologist/oncologist: Dr. Carrie Paul Hunter, UMMC’s second black medical student.

He also connected with the natural beauty of coastal Maryland, and with a hospital administrator named Delores Clair. A father of two, including a son who died about a decade ago, Oliver remarried.

Now, about five years into his retirement, he and Delores Clair Oliver have made a permanent home in Chesapeake Beach overlooking the bay on Maryland’s western shore. He has lived the life of the man his mother once worked for, and made it his own.