Front and Center: Traci Wilson

Brain cancer didn’t stop Traci Wilson from showing up for her patients and training the next generation of nurses to do the same.

At the University of Mississippi Medical Center, patients and nurses alike know Wilson, 39, as the one who never backs down. She’s the one who makes them laugh, who tells it straight, who shows up even when she shouldn’t be able to.

What many don’t realize is that Wilson is living with an inoperable brain tumor. His name is Pedro.

“When my little sister was 15 and driving me to radiation every day, she got tired of hearing everyone call it cancer,” Wilson said. “So, I asked her if she wanted to name it. She lit up. We landed on Pedro. Now, in my family, it’s not cancer—it’s just Pedro. If I’m tired, Pedro’s tired. If I’m in a bad mood, Pedro’s being difficult.”

For Wilson, naming her tumor was a way to claim power over something she couldn’t control. And choosing to return to nursing, despite a life-altering diagnosis, was her way of showing Pedro who’s boss.

Wilson didn’t always know she was meant to be a nurse. In fact, she resisted it. With a long line of nurses in her family—including her mom, five aunts, her older sister and now even her younger sister—she had planned to become a lawyer. But after one semester at Ole Miss and a summer of science courses at East Central Community College, fate had other plans.

“My professor, my husband and my mom basically decided I was going to nursing school,” she said. “I told them I’d give it two weeks. If I hated it, I’d quit. But I didn’t. It turns out I’m a nurse through and through, whether I wanted to be or not.”

She started her career at a long-term acute care hospital, was thrown into high-acuity care without much training, and quickly realized how much education matters. “That’s what made me want to precept. I didn’t get support as a new nurse. I want to be the support someone else didn’t get.”

She spent 10 years in home health, worked at a dialysis clinic and was one of the first COVID relief nurses during the pandemic. In 2019, she joined UMMC as a relief nurse and helped open 7 South. When the COVID unit launched, she was transferred to 2 North.

Four months in, she started feeling numbness on the right side of her body. “I thought it was from the drive, or maybe from pulling patients. I almost didn’t say anything. But I’m glad I did.”

She pushed for imaging, and after multiple hurdles—including a denied CT and hours-long wait due to pandemic delays—she finally got an MRI. The result: a glioblastoma, one of the most aggressive forms of brain cancer.

“I got the call after working night shift. I was trying to sleep,” she said. “My provider told me to come in right away. I didn’t want to. She ended up calling my husband and my mom. That’s when I knew it was serious.”

Most people in Wilson’s position would have taken a leave of absence. But she finished her contract hours before scheduling her brain biopsy.

“I had about two weeks left. I said, ‘I’m going to work them. Then I’ll have surgery.’ That was April 23, 2020. They gave me five years. And this April was five years.”

She underwent 42 days of radiation and six months of daily oral chemotherapy amid the chaos of the pandemic. With no short or long-term disability and ineligible for unemployment, it was a struggle financially and emotionally. Wilson named her tumor, but she never let it define her.

After treatment, she began pushing to return to UMMC, but her care team was hesitant. She lives more than an hour and a half away in the small town of Madden. She was still experiencing seizures. But she persisted.

“I convinced them to let me come back one day a week. Then two. Then three. That’s my max now— three shifts a week. But I give it everything I have.”

Back on the floor, Wilson returned to her favorite role: teacher. She has mentored dozens of new nurses at UMMC—some of whom still call her “Mama Traci” to this day. She’s known for her tough love, big heart and insistence that her trainees learn not just how to do the job, but why.

“It’s not just about sticking an IV,” she said. “It’s about reading the patient, listening to what they’re not saying and having compassion. That’s what I teach. That’s real nursing.”

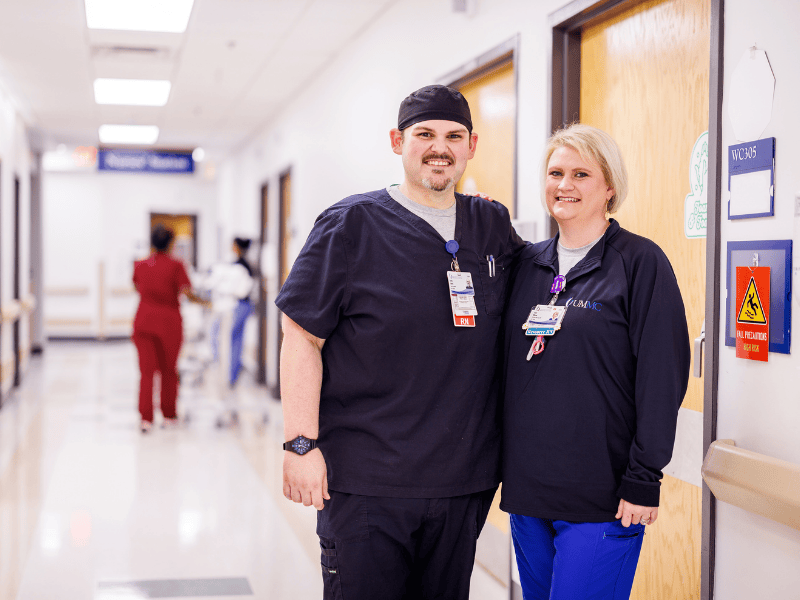

Two of her former trainees, now full-time nurses, credit Wilson with shaping their careers. One of them, Mason Norman, was a tech in the float pool when she met him. “He had just failed his third semester of nursing school by a hair,” she said. “I told him to try again, and when he graduated, I told him: come back, I’ll train you. Now, he walks into any unit and people say, ‘Where’s Mason?’ He’s amazing.’”

“Traci was my preceptor and played a pivotal role in shaping the nurse I am today,” said Norman. “Despite the odds, she continues to work full-time as a nurse while bravely battling cancer. Traci is an exceptionally compassionate caregiver who consistently goes above and beyond for her patients. I believe her story deserves to be shared so that others can be inspired and find strength through her testimony.”

Nurses and patients alike have found hope through Wilson’s resilience and optimism. Once, during a single shift, she cared for four brain tumor patients. Among them was Ervin Davis.

"A few years ago, I was diagnosed with a brain tumor, and I came here for surgery to get it removed,” Davis said. “When they brought me to the floor, Traci was my nurse. She shared her story with me and was just very optimistic. She had a very good attitude, and it just made me feel like I was going to be okay.”

Wilson recalled that she turned on the lights, opened the blinds and began talking about Pedro.

“I just wanted to make him laugh. Get him to eat. Get him to feel human again.”

Years later, Wilson was shocked to see Davis back at UMMC—not as a patient, but as a nurse in training.

“I always worked on the business side of things,” said Davis. “Everyone always told me that I’d make a great nurse and encouraged me to go back to school to do this. Just talking to Traci and seeing how she has continued to be so resilient made me realize that I can do it, too.”

“He told me I was the reason he went back to school,” Wilson added. “He said, ‘You reminded me my tumor didn’t define me. So, I decided it wouldn’t.’ That’s what this work is all about.”

Wilson still undergoes chemotherapy every two weeks—now through IV—and continues to have regular scans. “Stable” is the word she hopes for. The tumor in her left frontal lobe causes fatigue and occasional double vision. She still has seizures, but after trying four different medications, they’re mostly under control.

“I’m not supposed to drive when I’m having double vision, and I don’t,” she said. “But otherwise, I live my life. I work. I laugh. I train. And if Pedro’s having a bad day, I rest.”

She’s learned to listen to her body, but also to trust her purpose. On her days off, she and her husband enjoy time at the river or planning their next cruise. They just celebrated 20 years of marriage and have checked off most of the items on a bucket list she made during treatment, including trips to Disney and concerts by Alan Jackson, George Strait and Eric Church.

Wilson never got the chance to have children. But her “babies,” as she calls the nurses she mentored, are everywhere.

“I may not have kids of my own,” she said. “But I'm raising a generation of nurses.”