Leading with Love: Psychologist finds kids at the heart of her calling

Editor's Note: A version of this story first appeared in the summer 2022 issue of Mississippi Medicine.

The boy in the hospital bed wore a cowboy boot on just one foot when Dr. Gabrielle Banks first saw him.

He had tried to help his grandfather mow the lawn, and now his bootless foot was missing two toes.

Banks, a psychologist who was seeing pediatric patients in this Texas hospital, asked him if there was anything he would do differently next time.

“He told me, ‘I think I’m going to stick to the weed whacker,’” Banks recalls. “Five years old and he says that; and I thought, ‘I don’t think I will ever not want to work for kids again.’”

She brought that thought with her three years ago from Houston, Texas, back to her hometown of Jackson, where she unpacked it and has made the most of it at the Medical Center outpatient clinic providing mental health services for children.

“First and foremost, she has heart – a heart for the kids and the need to see the improvement of these kids,” said Dr. David Elkin, executive director of UMMC’s Center for the Advancement of Youth (CAY), which Banks joined as an assistant professor of pediatrics and a child psychologist fresh from her fellowship at Texas Children’s Hospital.

“I’m just impressed that she decided to come home. She went to the University of Pennsylvania which is, of course, an Ivy League school, and came back to Mississippi. She could have gone anywhere.”

Coming home was easy, Banks said. “I was ready.”

LIKE FATHER/LIKE MATLOCK

Home is where she practically grew up lingering in the corridors of justice and academia.

In Jackson State University’s Department of Psychology, she drew pictures in the hallway while her mother taught in the classroom. Dr. Pamela Banks is still professor and chair of the department.

Home is where she roamed the court building where her father made his name: Fred Banks served on the Mississippi Supreme Court for 11 years.

“I wanted to be a lawyer, when I was between the ages of 5 and 13, because, yes, I wanted to be like my father,” Banks said. “But I also wanted to be like Matlock.”

What she finally became had less to do with her parents’ love of their professions and more to do with their love of learning.

“With an African American family, knowledge is a powerful thing,” said Banks, who has two older siblings, Jonathan Banks and Dr. Rachel Banks, a family medicine physician.

“My brother is one of the first people I knew who lived outside of the South, traveled the world, and still expressed a fondness for Mississippi. He shaped by love for my home state.

“My mother was the first African American woman to graduate from the University of Southern Mississippi clinical psychology PhD program.

“It was clear to me that both my parents valued being able to serve people, to acquire knowledge and use it as a tool, not only to help people, but also to make a larger difference.

“You were going to school to learn how to help improve the human condition.”

She didn’t need school to teach her how to improve one human’s condition.

“My paternal grandmother had a severely debilitating stroke before I was born,” Banks said. “For the first 14 years of my life, I saw how my mother and sister and aunt cared for her.

“Sitters for her came daily to the house, but in the evening, when she needed assistance bathing or for other needs, my mom and aunt and sister would help her. That is a clear memory.

“It gave me an unspoken sense of responsibility, not only to serve people, but to also take care of them and take good care of them as long as you are able.”

Throughout many of those years with her grandmother, Banks was a student at St. Andrew’s Episcopal School. Her grades were her passport to the University of Pennsylvania, where two things stole her heart from TV lawyer Matlock.

“One was a seminar I took on trauma,” Banks said. “And one was a course on the history of American law after 1865.”

They had awakened within her a fascination with the human mind – not so much with what it could produce, such as laws – but with how and why it formed certain thoughts and ideas, in ways that differed so widely, depending on its owner.

“I was interested in how people came to make these decisions – some in the face of adversity, while some make decisions that disadvantage other people,” she said. “I decided I was going to be a psychologist.

“But the journey to wanting to become a child psychologist is more convoluted.”

That journey started in Jackson as well.

After undergraduate school, Banks returned to the Jackson area, where she worked for money at a shopping mall and for free as a research assistant at UMMC for Elkin and for the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior.

“[Elkin] and a psychiatric nurse let me shadow them and psychology residents who saw kids in the clinic,” Banks said. “I saw the challenges that parents faced, the medical complexity.”

Two of the children taught her something about herself.

“One was a girl undergoing cancer treatment, but she was also undergoing treatment for a disorder related to her anxiety,” Banks said. This hit home for her: Children with illnesses must deal not only with the discomforts of the body, but also with the discomposure of the mind.

“There was another child, also with cancer,” Banks said. “He had lost a significant part of his vision. And he was the life of the party.

“It was one of the first times I recognized how much environment shapes behavior in children. The boy was one of the first kids who allowed me to connect those dots.” She had also connected with children in a way that perhaps she hadn’t before.

“I was going to be a pediatric psychologist,” she said. And then she connected with the University of Memphis.

WITH HUMOR TO BOOT

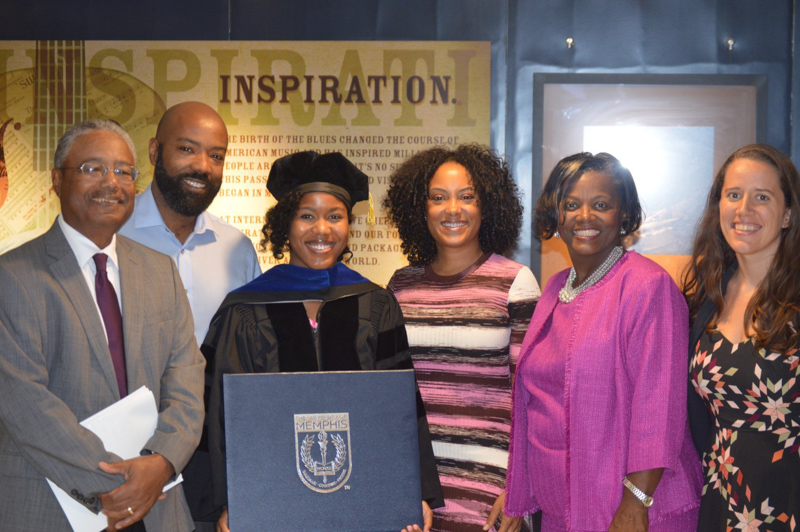

With a recommendation from Elkin, Banks entered the master’s degree program at Memphis, then earned a PhD in clinical psychology and met young patients at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and at Le Bonheur.

Later, during her fellowship at Texas Children’s Hospital, she came across the boy with the cowboy boot. “Meeting him illustrated for me that kids may be hurt, but they are also strong,” Banks said.

“What stuck with me is the hope that kids will be able to bounce back. And 5-year-olds can bounce back with humor.”

While still employed in Houston, she traveled to UMMC for a job interview. Dr. Barbara S. Saunders, medical director of CAY, was among those Banks impressed.

“Since she has been here, she and I have built a really great rapport working together to rule out autism for new patients,” said Saunders, associate professor of pediatrics and chief of the Division of Child Development.

“She tries to make sure parents and caregivers understand what we’re talking about, but not in a way that makes them feel as if she’s talking down to them.”

At CAY, Banks sees youth ages 18 and younger, and concentrates on disruptive behaviors in children ages 2 to 6.

She is also a clinical supervisor for the psychology residency program and a clinical supervisor for the Magnolia Scholars, the practicum program for doctoral psychology students from other Mississippi universities.

Whatever she wraps her arms around, she said, “I try to remind folks, and myself, that it’s OK to be wrong. There are strong emotions associated with being wrong, and sometimes that helps you learn; it helps you remember.”

A PERSONAL PASSION

Banks’ passion for understanding people with different experiences and identities became clear during a March 2022 podcast on Mississippi Public Broadcasting’s wellness radio program, “Southern Remedy Relatively Speaking.”

Asked how parents should respond if a child tells them, “‘I think I might be gay … and I don’t know what to do,’” Banks said the first thing to do is “lead with love.”

This message is at the heart of her own responses to the children she sees every day, making sure they know that, whatever they’re facing, whatever has wounded them – anxiety, depression, cancer or the cold-hearted edge of a lawnmower blade – they are not alone.