Clinical trial explores physical therapy for sports-related concussion, leg injury prevention

If a soccer player at one of Mississippi’s colleges or universities has good reflexes and motor skills that help with movement on the field, it could be a factor in whether or not they take a hit that results in concussion.

But can their sensory abilities impacting movement be adjusted for the better on the front end, lessening their chances of concussion, and allowing them to recover better and more quickly if they do suffer one?

A first-of-its-kind clinical trial by a research team at the University of Mississippi Medical Center aims to evaluate the effectiveness of aggressive physical therapy as “sensorimotor” training, which addresses the ability to take in sensory information and use it to direct your movement. Dr. Jennifer Reneker, associate professor of physical therapy, and a team of faculty, residents and students are putting Mississippi College men’s and women’s soccer players through a month-long exercise regimen that will help lead them to the study’s conclusions.

“We’re taking healthy athletes, who have had a concussion in the past or not, and seeing if we can fine-tune their sensorimotor system,” Reneker said. “I believe that if they have any underlying impairments, we can remedy that and decrease their risk of injury.

“The premise here is that there’s a likelihood that collegiate athletes have had one or more concussions, and many sub-concussive impacts that got them a little bit jostled,” she said. “It may have disturbed their sensorimotor function. That puts them at an increased risk of injury, and we know for sure that if you have a history of concussion, you have a higher risk of another concussion and a higher risk of leg injury.”

The trial, “Sensorimotor Training for Injury Prevention in Collegiate Soccer Players,” already is getting national attention on ClinicalTrials.gov. It’s funded through an internal research grant from UMMC’s Neuro Institute, which collaborates with researchers, educators, physicians and other health care providers at the Medical Center to build upon existing areas of strength in neuroscience in hopes of discovering new cures and developing improved treatments.

While working in Ohio before coming to UMMC in 2016, Reneker performed a clinical trial that studied very targeted, aggressive physical therapy “intervention” in athletes with a concussion to see if it would speed their recovery time after sustaining a concussion during sports. The group that had aggressive physical therapy got better faster than a control group that got no PT. “It showed us that sensorimotor training is effective in speeding recovery,” she said.

The current clinical trial is looking at prevention of injury. MC soccer players 18 and older were invited to take part in the trial, which began August 11.

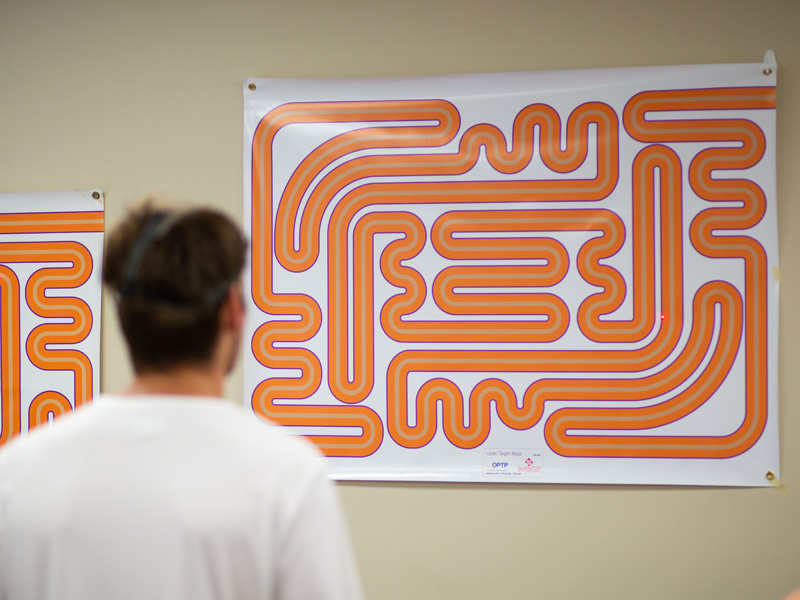

At the beginning of the trial, Reneker and her team performed baseline testing on 75 players that examined movement control of their eyes, their ability to use specific muscles in their neck in a controlled way, and their ability to focus their vision when their head is moving, among other things.

They’ll be tested again on those same abilities following the four weeks of training to see if there’s improvement. “We want to see if there are any clinical changes. We’re doing this to see if they can decrease their risk of injury while playing soccer” as a result of the trial’s activities, Reneker said.

Reneker and two others at UMMC – Dr. Cody Pannell, a physical therapy resident who received his doctor of physical therapy at the Medical Center, and Dr. Ryan Babl, an assistant professor of physical therapy – developed five different exercises for each of the eight sessions they will have with soccer players over the four weeks. That breaks down to two weekly sessions of aggressive physical therapy at MC for each athlete, led by UMMC team members. “We are training the same neurological pathways by using a variety of exercises,” Reneker said.

In addition, she said, players are getting homework.

“It’s all via video instruction. The home exercises are delivered on their cell phones, all on a private YouTube channel,” she said. “The link will be delivered by WhatsApp (a messaging app).

“It’s very millennial friendly. This is good for the athletes, and they will clearly see that there is potentially a real upside for them personally.”

Men’s soccer coach Kevin Johns said the therapy isn’t just for his players. “A lot of this is for myself,” said Johns, a 25-year coach, 16 of them at MC. “I want to learn about concussion. It’s a hot topic right now. I want to make a better environment for the kids, and for it to lead to fewer injuries.

“There’s the old mentality of the guys being tough and keeping their mouths closed about injuries. When they hear the word concussion … Maybe this might open their eyes.”

Babl’s role involves developing exercises targeting the deep cervical flexors of the neck, which are muscles having to do with positioning and motor control. “We will be teaching them how to activate and strengthen specific muscles, and to improve their endurance,” he said.

Some of the exercises use a device called an Iron-Neck to be strapped to the player’s head. “It uses a cuff to get a nice snug fit,” Babl said. “That allows us to tether a resistance cord to a fixed point, and it provides resistance for the muscles of the neck in each direction and for rotational movement when a player is in a sports-specific position.

“Think about how much your eyes play into how you react in daily life,” Pannell said. “If you were to chase down the soccer ball, you have to find it in space. You have to have good depth perception, but it might be off, and you could run into the defender in front of you.”

“We want to see whether their abilities to use the muscles of the neck can help them,” Babl said. “Does it influence decreasing the rate of experiencing a concussion? Does having the ability to strengthen these muscles help the player to be less susceptible to injury? And if they do receive an injury, do the exercises help them recover from a concussion more efficiently?”

Reneker and her team will compare the number of concussions and leg injuries suffered by the athletes this season with those recorded during the 2017. The exercise therapy will only last a month, but the UMMC team will track injuries for the entire season, she said.

“We will also find that there are going to be students who have clear weaknesses in some of the abilities we will be training for,” she said. “I think we will be able to show some clear improvements. And if they’re perfect, we will be super-training them to be even better than they are. Either way, this intervention should help you in sports.”

The soccer players include sophomore biology and pre-med major Caitlyn Sheppeard, 19, of Caledonia. She calls the exercise regimen “really cool.

“This will help my balance in competing. It will help me not to get hurt,” Sheppeard said. “A lot of players miss some of their best seasons because of injuries. You miss out on the game you love.”

“It’s really fun,” said sophomore sports marketing major Paul Downey, 19, of Birmingham, Ala. “I like to learn about it and understand what they’re doing. It can help everybody in the athletics department.”

He specifically wants to improve his peripheral vision. “In any sport, there’s just a lot going on,” Downey said. “Being able to see to the side will really help me overall in the game.”

“This is a frontier that we’re still exploring,” Babl said. “What are all of the factors that contribute to concussion, and what all is affected following concussion? If we can find out some of those factors, hopefully we can help reduce the rate of concussion injuries in these athletes and others in sports or professions where concussion is a risk.”

Keeping the athletes on track is necessary to the trial. “When you are looking at that many kids and trying to get them organized, balancing their schedules, it can be difficult,” Pannell said. “We are seeing kids from 7 a.m. until 5 p.m., three or four times a week.”

Girls’ soccer coach Darryl Longabaugh is grateful for his players’ involvement in the trial. Although taking part is strictly voluntary, he said, all of his athletes are eager to be involved. “Dr. Reneker is doing a great job with this, and I’m really excited to be a part of it.”

Players are at their greatest risk for concussions when they have contact with another player, or when they fall, said Longabaugh, in his 22nd season as girls’ soccer coach.

“We’ll have better awareness of concussion. The girls will learn how to train their bodies better, especially their necks,” he said.