Facial reanimation surgery offers something to smile about

When COVID-19 began raging in March 2020, Dereck Moore was on the front lines as a paramedic with the Choctaw and Neshoba County fire departments.

The deadly virus was bad enough. Moore being diagnosed with an aggressive brain tumor in the midst of that pandemonium was just as challenging.

“The bad thing was that it was in the first part of COVID,” said Moore, 57, a resident of Enterprise.

On March 23, he celebrated one year of not just survival after brain surgery at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, but recovery of his ability to smile, eat, drink, walk, speak and save lives at the job he loves passionately.

His journey involved two surgeries, the first being removal of the tumor by Dr. Gustavo Luzardo, associate professor of neurosurgery. The tumor likely would have killed Moore if it hadn’t been flagged during a routine eye exam.

The second, though, was an uncommon procedure to reverse facial paralysis he suffered as the result of the tumor removal. Dr. Randall Jordan, professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery, performed that surgery.

Moore said his first inkling that something was wrong came in late 2019 or early 2020 after he began having severe headaches. A couple of months later, Moore said, he had a routine appointment with his eye care provider who quickly realized something was amiss.

“He said, ‘Dereck, do you have problems looking to the right?’” Moore said. “I told him that I could only turn my head so far, and that I couldn’t focus in. He sent me for an MRI.”

Another key sign that something was amiss was Moore’s loss of hearing in one ear. “When one side disproportionately loses hearing compared to another, it should be investigated thoroughly,” Luzardo said. “It’s not just an age-related decline.”

News that he had a five-centimeter tumor was devastating. He was at work when he got the call from his local provider. “She showed me the MRI, and she’d already called Dr. Luzardo and set up an appointment,” Moore said. “They didn’t want me to drive or work. I had to quit cold turkey. They were worried about the tumor causing even more damage.”

When such a tumor occurs, Luzardo said, “hearing loss, loss of balance and impairment of rapid movements of the body creeps up very slowly.’

The type tumor experienced by Moore “grows consistently until it reaches the point where it compresses the brain stem,” Luzardo said. “At some point, Mr. Moore was unable to have a cell phone conversation in the affected ear. By the time a patient realizes that, the tumor is quite sizeable. Size of the tumor is everything when preserving facial function and hearing.”

Luzardo “told me there could be side effects and what to expect” following surgery to remove the tumor, Moore said, but it still came as a shock.

“When they had me in physical therapy the second day in the hospital, I hadn’t looked in the mirror yet. My face looked like it had melted on one side. I had to sit back down. I almost started to cry.”

Moore remembers the isolation of being sick during the early part of the pandemic. “I was in the hospital for five days without seeing my family,” he said. “But, the hospital was great. I can’t say enough about Dr. Jordan and Dr. Luzardo.”

He especially remembers the kindness of a nurse who cared for him immediately after surgery, when he was having difficulty eating unappetizing pureed food. “She came in one night and said, ‘You didn’t eat your food.’ I told her, ‘I just can’t.’

“Then she said, ‘Do you like mashed potatoes from KFC?’ She brought me some, and I ate every bit. It was so good.”

Luzardo told Moore before his March hospitalization that Jordan would be able to perform surgery if he suffered paralysis. “There’s an intimate relationship between the nerves and the tumor that made it impossible to separate them,” Luzardo said. “We committed to removal of the tumor, and moved quickly to face reanimation.”

Surgery for the brain tumor “required the cutting of the nerve to his facial muscles,” Jordan said. “We use a different nerve to attach to the facial nerve to supply input to the muscles of expression in the face.”

On May 7, 2020, Jordan transferred a nerve from one of Moore’s legs to his face. “This will eventually allow him to spontaneously smile once the nerve fibers have regrown,” Jordan said.

“This is not very commonly done,” he said. “Nerve transfers are typically done at major medical centers, and it can only be done within two years of the injury. Patients do better the earlier they receive the nerve transfer, and Mr. Moore was only a few months out from his brain surgery.”

Moore said he at first didn’t place much stock in the second surgery. “It was like, ‘Yeah, right. This sounds like a lot of hocus pocus.’ But to look at me now …. You wouldn’t even know I had needed the surgery.”

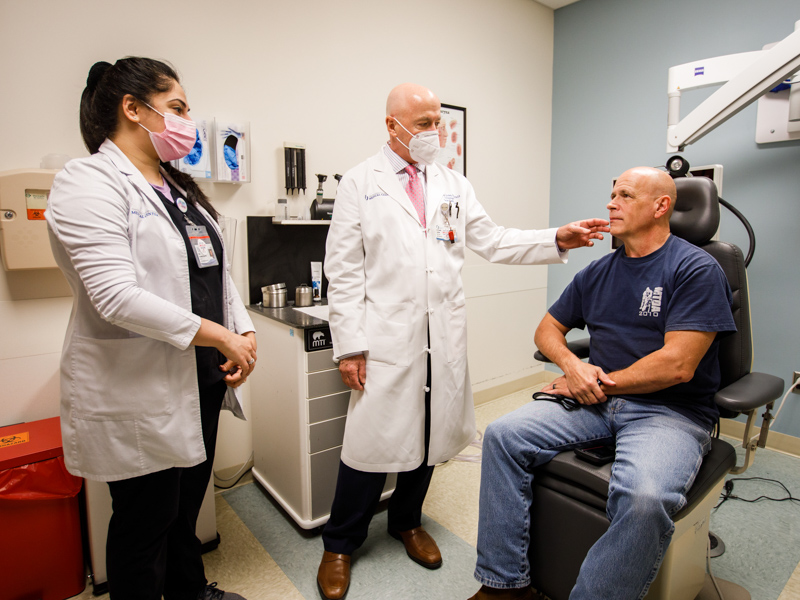

At his March 16 checkup with Jordan, Moore got a good report: His facial movement is progressively improving.

“Give me a big smile!” Jordan instructed. “Let me see you try to whistle. You’re getting your function back, that’s for sure. You’re getting more movement in your forehead.”

Moore is a “star patient,” said Rinki Varindani Desai, adult outpatient lead speech-language pathologist, who rehabilitated Moore to help him regain his ability to speak and eat.

“I have trained him to do facial reanimation exercises to bring back his function as much as possible and to maximize his quality of life,” Desai said.

Moore also is being seen by Dr. Thomas Eby, professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery, for treatment of fluid in his middle ear stemming from his initial surgery.

Moore said his therapy has included sessions at Anderson Regional Medical Center in Meridian. “I’m on the SWAT team in Meridian as a medic, and the therapist had me bring my SWAT vest – 40 pounds – to wear during my physical therapy. They put me through the ringer,” he said.

Although nerve transfer surgery is fairly rare, there are many patients who can be helped by it, especially those suffering injuries from surgery or a trauma, Jordan said. “The most common reason for facial paralysis is Bell’s palsy, a viral infection of the nerves,” he said. “Most patients recover fairly well, but there are some who don’t, and they could be a candidate for surgery.

“For any facial paralysis, there’s almost always something we can do for help.”

Moore said he and his wife Jill, an ICU nurse at Anderson, are grateful for the good care he’s received. “The older we get, we just like spending time with each other and doing stuff,” he said of Jill. “A good place to eat is more important now.”

“It’s just a night and day difference,” Moore said of regaining the use of his facial muscles. “It’s a miracle. I’m so glad they can do this at UMMC.”

“If you look at him a year from now, he’ll be way better,” Jordan said.