Edelman lecturer explains nation’s deeper pockets, shorter lives

Published in News Stories on September 21, 2015

Money can buy health. It can buy time and a longer life.

If that's the case, the United States should have the fittest, most long-lived population on earth.

But the country that spends more on medical care per person than any other nation in the world ranks last or near the bottom for several signposts of health, including life expectancy. How can this be?

Dr. Paula Braveman posed that question here Thursday before offering a multitude of responses during the second Marian Wright Edelman Distinguished Lectureship Series at the Jackson Medical Mall Thad Cochran Center.

"Health professionals are trained to deal with health effects - not the causes or the sources of those effects," said Braveman, the event's distinguished lecturer, who also directs the Center of Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

"Dealing with the sources is more difficult politically," said Braveman, a UCSF professor of family and community medicine.

Beech

The woman for whom the lectureship is named knows about political battles. Marian Wright Edelman is a "tireless champion" for children's justice," Dr. Bettina Beech, associate vice chancellor for population health, said in her opening remarks.

The president and founder of the Washington, D.C.-based Children's Defense Fund, an international children's rights organization, Edelman became, in the midst of the civil rights movement, the first African-American woman admitted to the bar in Mississippi. She gave the keynote address at last year's inaugural event.

A 2000 recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom who continues to crusade on behalf of disadvantaged Americans, Edelman is "one of my heroines," Braveman told an audience of 60-70 clinicians, educators, representatives of community-based agencies, children's advocates and others.

Inaugurated in 2014, the conference suggests a plan of action for those committed to reducing health disparities, particularly for children.

For her part, Braveman has spent more than 25 years raising awareness of the social factors shaping child health, describing those conditions during Thursday's talk, "It's Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes."

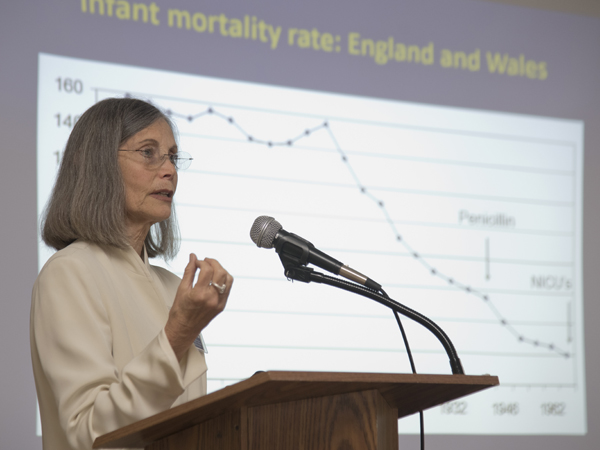

Over the decades, she said, improvements in living conditions - clean water, ventilation, sanitation, nutrition - have, more than any other influences, triggered drops in infant deaths, eclipsing the benefits of such advances as antibiotics, immunizations and the arrival of Neonatal Intensive Care Units.

Higher income and education are likely to equal improved health. "Children living in poverty are about seven times as likely to be in poor or fair health as children in the highest income families," she said.

Braveman used an upstream-downstream analogy: Pollution produced by an upstream factory contaminates the water drunk by downstream residents. Fighting the factory, or its harmful impacts, requires the political will to go upstream to the source. It means speaking out about the social factors that affect the health of all children, particularly those born in poverty.

Poor health, and poor health care, can follow children throughout their lives, Braveman said. "Some of the effects of deprivation in children are not erased in adulthood."

Tackling the "legacy of racial discrimination in this country," Braveman said, "People of color on the whole have lower incomes, less wealth, less education, less occupational attainments, live in poorer, less healthy neighborhoods."

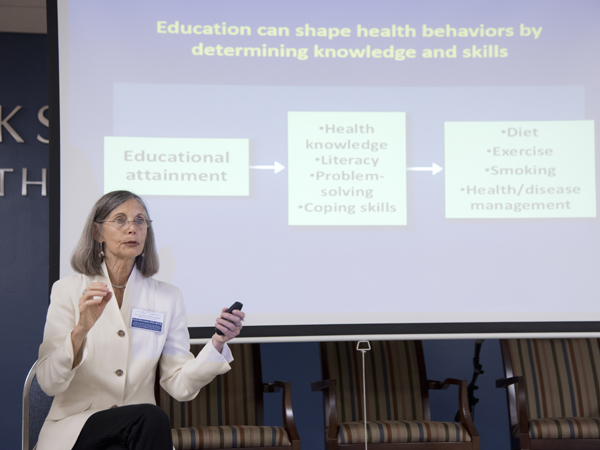

Braveman describes education's influence on health.

Racial inequity, she said, "is built into the structure." Children of families that have encountered racial discrimination are even affected psychologically, she said. When self-esteem is lowered, even among higher income families, health can suffer, "even without overt incidents."

Going back to her original question about the discrepancy between this country's medical care spending and its health rankings, Braveman said, "Is the answer that we aren't addressing the environment?"

"What can health providers do?" she said, offering these approaches: Recognize the role of social factors; identify the needs for social services and push for improved public health and health care; advocate for policies to shrink health disparities by addressing poverty and the lack of affordable child care, transportation, housing, safe and affordable places for physical activity and more.

"When you speak as a health professional, when you advocate for such things as that public park … you have credibility," Braveman said. "That may be more powerful than the clinical care."

The Marian Wright Edelman Distinguished Lectureship Series, Focusing on the Social Determinants of Child Health, was sponsored by the Myrlie Evers-Williams Institute for the Elimination of Health Disparities, the Office of Population Health and the Department of Pediatrics at UMMC, and the Mississippi State Medical Association.

Panelists share optimism for Mississippi children’s health, education

Therese Hanna, far left, leads a panel discussion with, from left, Dr. Rick Barr, Dr. Janice Bacon and Dr. Linda Southward.

Any conversation about Mississippi children's health and academic achievement is bound to raise discouraging numbers, which was the case during Thursday's Marian Wright Edelman Distinguished Lectureship Series panel discussion.

But the dialogue, which followed Dr. Paula Braveman's presentation, offered several doses of hope and optimism as well from the three panelists: Dr. Rick Barr, UMMC's Suzan B. Thames professor and chair of pediatrics; Dr. Janice Bacon, pediatrician with Central Mississippi Health Services Center; and Dr. Linda Southward, coordinator of the Family and Children Research Unit at Mississippi State University and director of Mississippi KIDS COUNT.

Led by moderator Therese Hanna, executive director of the Mississippi Center for Health Policy, the trio did not dodge the bad news, though: 34 percent of Mississippi's children live in poverty, compared to 22 percent nationwide, as reported by the 2015 KIDS COUNT Data Book from the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

"It would take about four stadiums the size of Davis Wade to hold them all," Southward said, referring to MSU's football arena, with a seating capacity of more than 61,000.

As measured by KIDS count, Mississippi has ranked 50th among the states in children's well-being for 26 of the last 27 years, Southward said.

Referring to the state's political climate, Bacon said that social services and health-related prevention measures have seen reduced funding and reimbursements.

The Women, Infants and Children's Nutrition Program (WIC) needs to be tapped into more, Bacon said, and the potential of the federal Head Start program, an early education program for children of low-income families, is not being met.

In addition, Barr said, many agencies trying to meet the needs of the state's children act independently. "They don't talk to each other," he said.

The panelists agreed that more comprehensive funding for early childhood education is vital. Southward offered newly-arrived evidence to back that up: a study released this month by the Family and Children Research Unit shows that 4,100 Mississippi children who attended pre-K were 1 ½ times more likely to be proficient in third-grade reading and are nine times more likely to be proficient readers in the eighth grade.

Those eighth-graders are 3 ½ times more likely to graduate on time.

"We keep hearing, 'show us the data,'" Southward said. "Well, here's the data."

Other signs of improvement or reasons for hope include the state's, and nation's, significantly lower teen birth rate.

And, Barr said, such measures as the legislatively-authorized Mississippi Rural Physicians Scholarship Program, still relatively new, will place more and more physicians in medically-underserved areas, and, over time, "improve health outcomes."