ALS explained: UMMC experts put patients' quality of life first

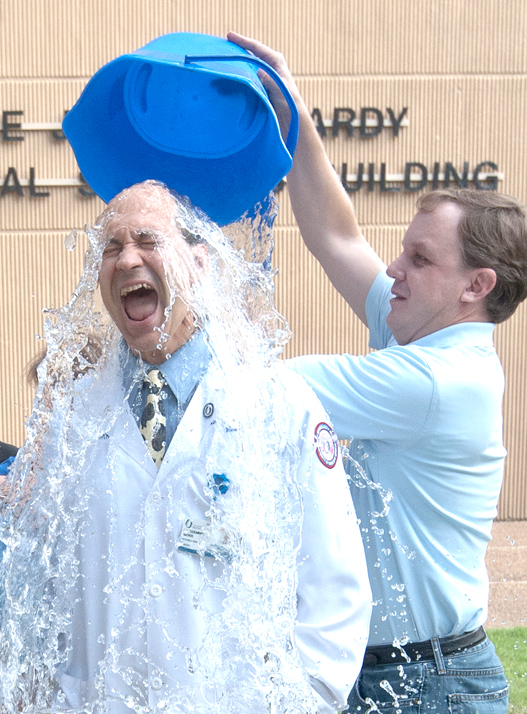

Taking the Ice Bucket Challenge to raise money for ALS research is one thing.

Understanding not just what ALS stands for, but what it does to your mom, best friend or next-door neighbor is another, experts in neurodegenerative diseases at the University of Mississippi Medical Center say.

Here’s what generally happens, not necessarily in this order, and not necessarily over the same period of time: Muscles all over your body become weak and shrink. Limb by limb, body part by body part, you lose function. You cannot walk. You can’t use your hands.

As your face and tongue muscles waste away, your speech becomes impaired and you lose the ability to swallow. In the disease’s final stages, muscles that allow you to breathe no longer function. You can become totally paralyzed. What’s keeping you alive is a ventilator and feeding tube.

Your mind is as sharp as the day you were diagnosed, which likely happened two to four years earlier. You have feeling, but not movement. Your hearing and eyesight are usually just fine.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, is always fatal. For a newly diagnosed patient, “it’s extremely scary. It’s like giving someone a death sentence,” said Dr. V.V. “Veda” Vedanarayanan, professor of neurology, pediatrics and pathology in the School of Medicine.

Muscle movement occurs when motor neurons in the brain signal the motor neurons in the spinal cord. Motor neurons in an ALS patient die, and the ability of the brain to initiate and control muscle movement is lost.

“You know exactly what’s going on,” Vedanarayanan said. “You used to be able to do something, and now you need help. When you’re not able to breathe …. That’s when it’s fatal.”

The mother of girls ages 7 and 10 can’t walk or use her hands and arms. She has a lift recliner, an electric wheelchair and a hospital bed that help her cope. “I’m not always comfortable, but I make do,” Armstrong said. “My husband works overseas and during the week he’s gone, so I have to have someone with me 24 hours a day.”

About one in 100,000 people are diagnosed with ALS, usually no earlier than in their 40s or 50s. Although much remains a mystery, it’s been tied to genetic abnormalities, said Dr. Alexander Auchus, professor and McCarty Chair of Neurology.

Just as someone taking the Ice Bucket Challenge sucks in his breath as ice-laced water is poured over their heads in exchange for a donation, a person getting a diagnosis of ALS is equally shocked. “There’s not a particular test we can do that will confirm the diagnosis. We might wait, or get a second opinion before we confirm,” Vedanarayanan said.

UMMC’s neurology staff cares for an average 20-25 ALS patients. “We aren’t just focused on a diagnosis. We start supportive care right off the bat,” Vedanarayanan said. “That can be therapy, helping them through finances and their job, nutrition, equipment needs and special beds, figuring out if they have money to pay their bills. Medicare benefits kick in immediately.”

Occupational and speech therapists evaluate communication and nutrition. “Patients might first experience problems with their voice,” said UMMC speech and language pathologist Kathy Wentland. She and the team give them high-tech communication devices ranging from iPads to devices controlled by a patient’s eyes. “It can be hooked up to email and the Internet so that they can stay connected to people,” she said.

Otolaryngology staff take X-rays to make sure a patient isn’t aspirating food into their lungs, she said. They get sophisticated breathing equipment, including portable ventilators and machines that push more air into the lungs.

“Our goal is to prolong oral feeding as long as we can,” Wentland said. “They may get fatigued over the course of a meal, so we recommend they eat smaller, more frequent meals, or eat more slowly and take smaller bites.”

And even with a feeding tube, “that doesn’t mean they can’t eat,” she said. “They may still be able to enjoy small amounts of food for pleasure.”

They may be given Riluzole, the one FDA-approved drug that can slow, if only by months, the progression of the disease. Nuedexta, a drug used to help people with uncontrolled crying or laughing, can help ALS patients who have “spasms of emotions” as their throat constricts, Vedanarayanan said.

Plans are under way for a specialized weekly comprehensive clinic for ALS patients at UMMC, Auchus said. Patients will get all services during the same appointment so that they won’t become exhausted so quickly, Vedanarayanan said.

Auchus, Veda and Wentland point to internationally famous Stephen Hawking, the brilliant theoretical physicist. For decades, he’s coped with a motor neuron disease similar to ALS. Hawking is almost entirely paralyzed and communicates through a speech generating device.

They hold onto hope that research funded by initiatives such as the ALS Association’s Ice Bucket Challenge, which to date has raised more than $23 million, will bear fruit for their patients. “We build a relationship as we go,” Veda said. “They come and see us, and we work through all of these things. They’re like family.”

Said Armstrong: “There’s no cure, but I’m thankful for the awareness. Even if I don’t receive a cure, someone else will not have to go through this.”