People of the U: Dr. Thomas Helling

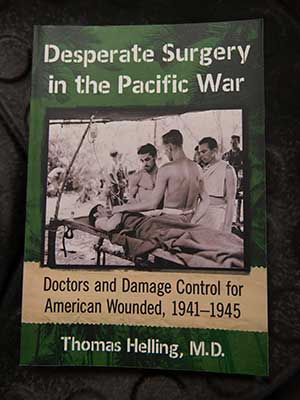

Dr. Thomas Helling doesn’t plan to strike it rich with his new book about the courageous physicians and surgeons who preserved life amid the carnage and chaos on the Pacific islands during World War II.

He took on the labor of love because their stories need to be told.

Desperate Surgery in the Pacific War: Doctors and Damage Control for American Wounded, 1941-45 is partially borne of Helling’s career experience in trauma surgical care and his service in the U.S. Army Medical Corps. But more than that, he sees the need to document the personal experiences of surgeons who toiled in the Pacific Theater – “a human side, rather than just dwelling on facts and figures,” Helling said.

“I’ve been sort of an amateur history buff on surgery, and it dovetailed into me writing about the conflict in the Pacific during World War II that required innovative techniques to deal with seriously wounded soldiers and Marines,” said Helling, professor and chief of the Division of General Surgery. “The concept of damage control was developed formally in the 1990s, but actually, it wasn’t so new. It was really developed in the Pacific Theater on or near the battlefields.”

The mission of those physicians and surgeons, many fresh out of internship with limited or no experience in trauma medicine, was simple: patch up soldiers injured by the Japanese until they could be taken to a higher level of care. And do it in extreme circumstances as battles raged around them, knowing that the closest ICU is where they’re standing.

“Some of the island conflicts were very remote, and very austere, as compared to the European theater,” said Helling, who served nine years in the Army Reserves and received an honorable discharge in 2000 as a lieutenant colonel. “Getting soldiers to a hospital ship and specialized care might take days. In Vietnam, you had helicopters. Transport was sometimes an hour or less. ”

Much of the patient care on the Pacific islands was basic, such as stopping bleeding and assessing soldiers for life-threatening injuries. If a soldier was all but disemboweled by gunfire, or suffered a gaping head wound, the battlefield medical team dealt with it.

“They were thrown into situations as dangerous as those of the troops they were sent to care for,” Helling said. “Their ability to calmly look over the injuries, start blood, stop bleeding, all the while under gunfire and shellings … I just can’t imagine what courage it took. On some of these islands, the fighting was so violent and the number of casualties was so great.”

Resources were few amid the islands’ thick jungles and remote atolls. On-the-fly innovation was the norm. “I can’t imagine the American public tolerating that today,” he said. “The number of injured was simply overwhelming.

“I was impressed by the willingness of these surgeons to try new techniques that we now think of as standard,” Helling said. “To them, they were unproven, but there was nothing else to do so that they could save lives or limbs that were endangered.

“With the wars and conflicts that followed in Korea and Vietnam, the repair of blood vessels became standardized, but some of those techniques were tried for the first time in World War II,” Helling said. “There were also remarkable advances in surgery of the intestines and colon. Before that, it carried a very high mortality.”

Helling’s research was exhaustive. Personal interviews were impossible – all the physicians had died -- but he spoke with some of their relatives to capture their stories.

He scoured official records, including physicians’ reports of their activities and casualties treated. “I talked to one or two surgeons who were a generation removed from World War II to get their take on it,” Helling said. “There was an official history written after the war, but it was pretty dry stuff.”

The horrors of war extended to hospital ships transporting the wounded. They were attacked, too.

“Some of these poor sailors were thrown into the water, and they floated on pieces of debris for days,” Helling said. “The doctors thrown into the water with them tried their best. They were trying to keep themselves alive and doing what they could for the sailors who were burned or maimed. Some were on life rafts, but many of them drowned or were eaten by sharks.

“You cannot believe the carnage that these poor guys went through, and still in the midst of the threat, you have the care that they were able to render, and the survival they were able to produce,” he said. “In current conflicts like Iraq and Afghanistan, there are ghastly injuries, but there’s also the capability to get those soldiers sophisticated care within hours. We take that for granted.”

Some might think what Helling’s researched showed is nothing short of amazing. “The survival rate was almost as good as it is now, thanks to those physicians and surgeons. They did damage control early in the care of the severely injured, and got them stabilized and to a higher level of care.”

He’s gotten positive feedback on his book published by McFarland, a leading independent publisher of academic and nonfiction books. The Army University Press’ Military Review, the professional journal of the U.S. Army, praises Helling for recognizing the physicians’ daily struggles.

“Helling, an author of over 40 medical publications ranging from organ transplants to treating fractures in major trauma incidents, and whose father participated in the Pacific Theater, is the seemingly perfect person to tackle the unforgiving subject of trauma care in the Pacific Theater,” the review reads in part.

“Outside of Helling’s already excellent credentials as a medical professional, he uses an organized blend of primary and secondary sources consisting of casualty reports, treatment logs, historical battle reviews, medical journals, and personal journals kept by the medical professionals described in this book.”

Any glory goes to the soldiers, Helling says.

“It was rare that a physician shied away from their duties. Their stories need to be told, and it’s certainly something that we should emulate and honor.”