UMMC builds ventilators for COVID-19 pandemic response

The COVID-19 pandemic has left hospitals in short supply of personal protective equipment and medical supplies. As patients develop severe respiratory symptoms, there is another concern: if hospitals will have enough ventilators to support them all.

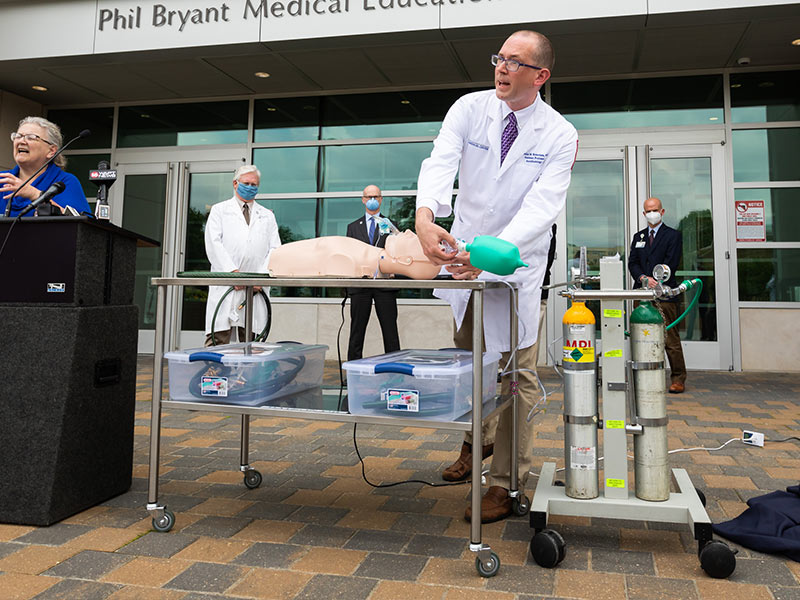

Dr. Charles Robertson, an assistant professor of anesthesiology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, has built about 170 ventilators of his own design to use in the event of a shortage, doubling the Medical Center’s supply.

“I was watching the coronavirus spread in China during January, then by the time February came and cases started increasing in South Korea, Italy and Iran, I knew it was coming to the United States, and that if enough people became sick, we may not have enough ventilators,” Robertson said.

Physicians and engineers around the world have been coming up with ways to increase ventilator capacity, whether by putting multiple people on one unit or building mechanical hands to squeeze manual devices, Robertson said.

His idea: to build the “absolute simplest, cheapest functioning ventilator from widely available parts,” he said

The Robertson Ventilators are made from garden hose sections, adapters, valves, a solenoid and a lamp timer, all of which can be bought at a hardware store or online. The parts cost less than 100 dollars per ventilator and can be assembled in less than an hour. The ventilator works when plugged into the standard oxygen line in a hospital room, meaning it can be used in more locations than a standard ventilator.

Ventilators work by pushing air into the lungs, then stopping for an exhale, then repeating as needed. Robertson’s design controls air flow using an on-off valve similar to what you’d find in a landscape water feature or lawn sprinkler controlled by the timer and the solenoid.

“We’ve been through a couple iterations of exact parts and assembly routines and have the process pretty streamlined,” Robertson said. “The goal was to create a ventilator with adequate operation and utmost simplicity in construction.”

Robertson and a team of UMMC certified registered nurse anesthetists have built about 170 ventilators to augment the Medical Center’s existing supply of 150 hospital ventilators.

“This device is for extreme use situations during a pandemic,” Robertson said. “We would only be using these ventilators if every single hospital ventilator is in use and we have patients that are about to die because of that.”

In these cases, it could be used as a “bridge therapy,” where a patient uses this ventilator for several hours while waiting on the hospital ventilator to become available.

“These ventilators have passed rigorous testing in our research laboratories under broad physiologic conditions and lung pathologies,” said Dr. Richard Summers, associate vice chancellor for research. “We have measured their ability to maintain clinical parameters such as oxygenation, carbon dioxide and tidal volume.”

Summers is working to get the ventilators approved for use. Sometimes referred to as compassionate use, this designation would allow the Medical Center to use them as approved medical devices if they must.

“We have filed for an Emergency Use Authorization with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration who have indicated their interest in these ventilators,” Summers said. “I think this effort represents the independent ‘can do’ attitude and ingenuity of our physicians and scientists to confront this crisis in the service of the people of Mississippi.”

Robertson tested the ventilator with the assistance of UMMC’s Simulation and Interprofessional Education Center and Center for Comparative Research. In the latter, the veterinary team used the Robertson Ventilator instead of the standard ventilator to maintain oxygen to laboratory animals for up to six hours.

Dr. John Prescott, chief academic officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges, has been in communication with Robertson about his ventilator.

“Innovation is happening at academic medical centers across the nation in response to the coronavirus pandemic,” Prescott said. “I recently had the opportunity to FaceTime with Dr. Robertson and was very impressed with his new ventilator. It’s simple, inexpensive and initial testing indicates it could be an extremely valuable asset in the coming weeks.”

The Robertson ventilator, although functional, lacks the more sophisticated features of a standard one. It lacks a bellows, which pushes air quickly into the lungs. In natural breathing, the inhale is faster than the exhale. Hospital ventilators mimic this action on their standard setting. However, Robertson said that people with depressed respiration, like those with severe COVID-19, sometimes need the opposite therapy: long inhale time, short exhale time. His design does that.

The ventilator also doesn’t have any alarm systems for malfunctions, but he is looking at ways to address that.

“I’m considering ways to attach a whistle to parts of the ventilator where we may experience malfunctions, but I’m still working on configurations for that,” he said.

While the ventilators are meant to be simple, inexpensive solutions, building hundreds of the units requires a more coordinated approach.

“We would welcome logistical assistance from Amazon and Home Depot, to help us to make more units,” Robertson said.