From the ER to the lab, Summers' career adds up

NOTE: A version of this article originally appeared in the Summer 2016 issue of Mississippi Medicine, the semi-annual alumni magazine for the School of Medicine.

Some people dream in color; Dr. Richard Summers dreams in math.

Even in college, he dreamed in symbols – actual mathematical equations, which flashed before him and rearranged themselves, like dialogue being polished by an invisible writer.

Even in his sleep, he was studying his favorite language.

This passion followed him to medical school, where his ideas on how the world worked had to be tweaked: “I spent the first week in Gross Anatomy looking in the body for the equations,” Dr. Richard Summers recalled, “and there were none.”

Even so, the vernacular of relationships and balance and odds has served him well – in the classroom, the emergency room, and for several years at NASA, where he and pharmacologist Dr. Jan Meck measured space travel’s toll on astronauts.

“He’s the most brilliant man you’ll ever meet,” said Meck, who directed NASA’s cardiovascular research lab before heading research at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.

“You give him hard intellectual problems to solve, and he’s happy. He lies in bed at night and reads math books.”

In fact, Summers has proven the hypothesis that in academic medicine and research, there are worse things to be than a math whiz.

A professor of emergency medicine with a joint appointment in the Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Summers has also been associate vice chancellor for research since 2013, succeeding Dr. John Hall, who led the research programs with distinction for eight years.

As the new Translational Research Center was hammered and hoisted into place right outside his office window, Summers watched his career at UMMC going up, literally, story by story.

Now completed, the $50 million, 124,852 square-foot structure represents the future of applied research, and by association, the future of the person who will oversee its work, in his uniquely qualified way.

“He approaches his leadership role as associate vice chancellor in the same way he approaches his job as an emergency medicine physician,” said Dr. LouAnn Woodward, vice chancellor for health affairs and dean of the School of Medicine.

“He’s analytical and thoughtful, yet creative,” said Woodward, a professor of emergency medicine who was one of Summers’ physiology students more than three decades ago.

“I consider Richard a mathematician who happened to go to medical school.”

Outside track

During his youth, Richard LeRoy Summers’ legs moved almost as fast as his mind.

At Gulfport High School, he was a wide receiver and defensive back for the football team; he was a track star in the 100-yard dash.

Summers was a true child of the Gulf Coast, where he lived much of his early life haunting the piers and piloting boats, and satisfying his thirst for salt-water fishing.

“I used to take my friend’s skiff,” he said, “and float 12 miles away to Ship Island – that was our front yard.”

Voyages – short, long, true and fictional – thrilled him. He was fascinated by the movie “2001: A Space Odyssey,” and by Jules Verne’s imaginary trips to the moon, the center of the earth and the bottom of the sea.

None of which was as gripping as a true-life World War II tale whose hero is his father.

A quarterback for the University of Miami in the 1940s, Summers’ father, Richard Lee Summers, was drafted first by the NFL’s Chicago Bears, “and also by Uncle Sam.”

Uncle Sam had first pick. Richard Lee was a bombardier assigned to the flight crew of a B-17 that was soon shot down over the North Sea, where he and his crewmates almost froze to death as they floated on a raft, until a German U-Boat fished them out and put them on ice in a prison camp.

Summers’ father escaped six times. Near the end of the war, he and fellow prisoners broke into their captors’ armory and took over the place. That was just after the Battle of the Bulge, fought by the famous American general who finally rescued them.

“My father saw Patton ride into camp,” Summers said, “his stars gleaming.”

It took at least six months before Richard Lee was reunited with his mother after the war. “My grandmother had moved from Florida to North Carolina,” Summers said. “She thought my father was dead, until he showed up on the front porch.”

In post-war Mississippi, Summers’ father built a comparatively peaceful life in Gulfport with his wife Doris and their three children as a Presbyterian minister. It was at his father’s church that young Richard Summers met a medical missionary from Korea, an encounter he never forgot.

Many other friends of the family also practiced medicine. “It seemed like a very practical way to help people,” he said.

But math would not let him go, not even in his dreams. It added up to a language all its own, and exploring it was like a Jules Verne journey to another world.

As an undergraduate at the University of Southern Mississippi, he studied very little biology. His majors were physical chemistry and, of course, math. He was not on the medical-school track, but that is where he landed.

Not only that, he would choose a specialty that seems, superficially, as far removed from the structured, organized system of mathematics as it could possibly be.

It calls for decision-making under stress, improvisation, daring and nerve.

Richard Summers was not the son of a physician. But as a physician in the emergency room, he was definitely his father’s son.

Breathing space

If mathematicians and scientists have a reputation – fair or not – as dispassionate observers of the world around them, then Summers disproves the premise.

Which may be hard to see, until you get to know him, said Meck, the former NASA scientist, who knows him well.

“I’m a big bird watcher,” said Meck, a Richmond, Virginia resident who retired about seven years ago. “When Richard would come down to NASA, I’d take him to this place in Galveston, to this shorebird rookery.

“Leafless trees were everywhere on this island, where there were thousands and thousands of nesting birds; and in spite of all the noise they made and the smell, I just couldn’t pull him away. He was mesmerized.

“He said, ‘I feel like I’ve been transported to prehistoric times.’ He saw the importance of protecting those creatures, and it was meaningful to me to stand there with someone who got that.

“He gets nature, he gets philosophy; he gets everything.”

Nine years ago, Meck developed cancer of the eye. “Richard flew down from Jackson to be there with me,” she said. “As a gift, he brought me a book. I looked at it and said,’ Richard, I’m having eye surgery tomorrow.’

“So we read it together overnight. The point is that he shows up; he’s a true friend.”

Friends mean a lot to him. Friendship is the reason he gives, more or less, for his career choice. “In college, they were interested in going to medical school,” Summers said. “So, at the last minute, I applied too.”

As impulses go, that was one fruitful whim.

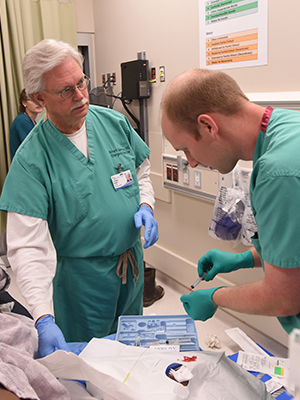

When he graduated from UMMC’s School of Medicine in 1981, emergency medicine wasn’t a specialty at the Medical Center, but it would be soon, and Summers would latch onto it.

His got his first taste of it during his research fellowship, while “moonlighting,” in the Emergency Department; there, the mathematician felt right at home.

“I thought of emergency medicine as a mathematics process involving probability,” he said. “Unlike, say a surgeon, who bases decisions on subjective data, as when operating on a patient’s cancer, in the emergency room, you’re using limited information; you need to make a quick decision that can be life-changing.”

Thriving in this setting, he rose to a professorship in the Department of Emergency Medicine, which he would eventually chair.

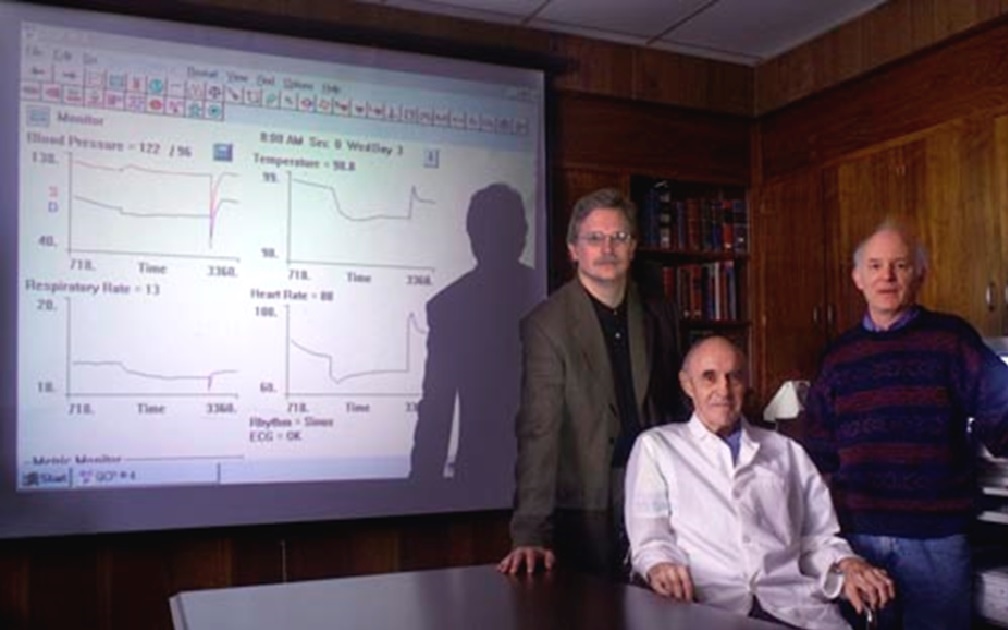

As for his career in research, that began with his post-doctoral physiology fellowship under Dr. Tom Coleman and the late Dr. Arthur Guyton. Together, Summers’ mentors created a mathematical model of human physiology that Summers would harness in his work with Meck at NASA as an outside consultant for 15 years.

“I was able to get very high-powered researchers to work with me just for the thrill of going to a Space Shuttle landing,” Meck said. “Richard was one of them. He received very little financial benefit, but did it for the sake of intellectual curiosity and to help the space program.

“We were able to use that great physiological model he brought to create a digital astronaut.” The researchers exploited the model to study, among other things, the effects of microgravity on a space traveler’s blood pressure and heart.

“In flight, an astronaut’s heart changes in space,” Meck said, “and the worry was that the heart was wasting away. Richard’s modeling refuted that. He said, ‘No, it was just a normal response to the lack of gravity.”

Summers’ work for NASA’s Digital Astronaut Program was a national reputation builder. He also has some 300 publications under his name. After the Space Shuttle program was discontinued, the mathematical model was inherited by Dr. Robert Hester, Billy S. Guyton Distinguished Professor and professor of physiology and biophysics.

Coleman, now a professor emeritus in the same department, said he’s still working on the model with Hester, and that Summers is also “in the mix.”

Coleman, now a professor emeritus in the same department, said he’s still working on the model with Hester, and that Summers is also “in the mix.”

“There is friendship, synergism and productivity here,” Coleman said. “The publication record speaks for itself. The UMMC family should be very proud of what Richard has done, and I, for one, am expecting still more from Richard in the future.”

Everyone is.

Mission statement

Summers, married now and the father of two, buried his own father about 12 years ago. Doris Summers moved from Gulfport shortly before Hurricane Katrina moved in and destroyed the family home in 2005.

“All the landmarks I knew growing up changed so much,” Summers said. “I love the atmosphere of the Coast, but it’s just not the same.”

A big part of the state he knew for much of his life – the people and places of his youth – have left, but he has no plans to leave it, he said.

“I believe this is the place I’m supposed to be and where I’m needed; plus, I’m a Mississippian.”

Obviously, there is a place for him at the Medical Center; it looms high above his office window, in plain view.

“The Translational Research Center,” Woodward said, “represents a historic institutional investment in research; certainly the largest in recent years.”

Its focus will be to bridge the gap between basic science and its bearing on patient care – important for UMMC, she said, “especially in the larger research environment.”

That environment is Summers’ province, as is his role involving the Mayo Clinic. About three years ago, UMMC and the world-renowned institution agreed to expand their collaboration in clinical trials, other medical research and education.

That relationship will abet health care’s move away from one-size-fits-all, evidence-based science to “precision medicine,” which is tailored to “the individual before you,” Summers said.

“Precision medicine says, for instance, that if you’re treating your patients for strep throat, you’re not going to give the same dose to a 300-pound lineman and a 90-year-old woman.”

Summers’ current role as associate vice chancellor for research lacks the climate of urgency that is the ER physician’s bread and butter. But there are slight similarities between the two jobs, he said.

“With any major leadership role, there is no way you can know all the particulars; you do know the general direction things are going in, and you make decisions based on that.” Still, he said, “no one dies.”

Research is one of UMMC’s three primary missions, and since the fall of 2013, Summers has led it. But the other two – education and health care – are still in his life.

He still teaches the occasional class – perhaps training another vice chancellor of the future.

And on Sundays, you can find him working in the ER, testing the laws of probability, still fascinated by equations – particularly the human one.