OT assists students in the occupation of learning

"As long as you are in school, your job is to make good grades." This is a phrase heard from the mouth of many a parent. A kid's occupation is to learn, play and grow.

That's why when a child is experiencing difficulty learning one of the basic building blocks of a good education — handwriting — an occupational therapist is called.

According to the American Occupational Therapy Association, handwriting is "a complex process of managing written language by coordinating the eyes, arms, hands, pencil grip, letter formation and body posture." Difficulty with handwriting can clue a teacher in to underlying developmental problems that can affect learning, according to AOTA.

Dr. Peter Giroux, professor of occupational therapy in the School of Health Related Professions, has been assisting children with special and exceptional needs for more than 20 years.

"The most frequent reason for an occupational therapy referral in the school system is difficulty with handwriting and related fine motor problems," said Giroux. "Handwriting is the student's primary way to demonstrate knowledge and understanding to the teacher."

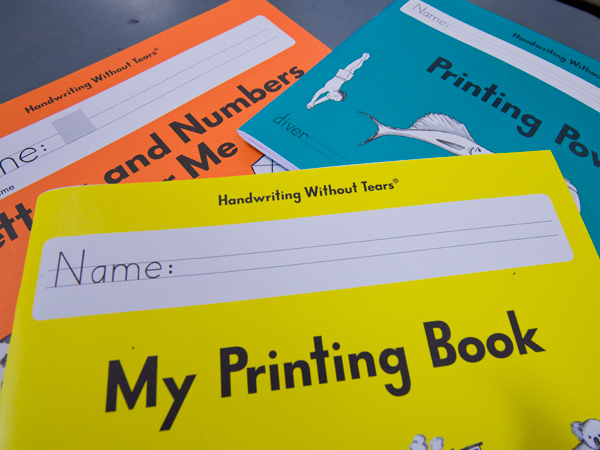

In 1995, Giroux began using a handwriting curriculum designed by Jan Z. Olsen, OTR, called Handwriting Without Tears (HWT). Olsen's method was born from her efforts to help her own son who in the late '70s was having difficulty with handwriting.

Olsen decided to use her skills as an occupational therapist to design a workbook and approach specifically for her son's needs, breaking handwriting down to developmental steps, arranging the material from simple to complex and teaching it in that order.

How Giroux and Olsen met is a bit of business mixed with southern hospitality and old friends.

"My college roommate's husband was a professor at Belhaven," said Olsen. "Her daughter had triplets, and she asked me to come down to help her. I said that if I fly to Jackson, maybe I can arrange to speak to the university's (UMMC's) occupational therapy department. Peter set it up so that I could speak to his students."

Giroux was happy to oblige. "I had been using her curriculum," said Giroux. "It wasn't very widespread back then, but it was a great curriculum. It uses a multisensory approach which is beneficial when working with children who learn differently.

"All children gather information through their senses. This is a natural way to learn and a natural way to teach. By teaching handwriting through numerous sensory pathways — visual, auditory, tactile — the teacher is able to appeal to different learning styles."

Allowing a child to touch objects and perform tasks during instruction improves skill retention. Olsen incorporated this approach into the HWT curriculum by using wooden building blocks as handwriting manipulatives to teach letter formation to at-risk children who were unable to hold a pencil.

With the wooden manipulatives — called Big Line, Big Curve, Little Line and Little Curve in the curriculum — a student can build all of the capital letters without picking up a pencil. Those same wooden pieces can be used to build Mat Man, a friendly character in the curriculum, who helps children learn letters, shapes and other concepts through the use of activities and music such as the Build Mat Man song.

"In January of 2000, Jan called me and told me that her company was growing, and she invited me to join as a consultant," said Giroux. "She wanted to incorporate national professionals to help present her curriculum to teachers, educators and therapists across the U.S."

Olsen chose to recruit occupational therapists for their unique qualifications.

"Occupational therapists would bring not only the training but personal experience and professional qualifications," said Olsen. "Many from that first group, including Peter, are still with us years later."

In the 16 years that Giroux has represented HWT, he has visited 42 states, Mexico, Canada, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Hong Kong and Singapore.

"The fascinating part of my work with HWT is that I get to travel all over the world and see the cases other countries are dealing with," said Giroux. "At one time, Singapore was ranked last for education in Asia. They decided to change that and went from ranking last to first in ten years."

Giroux has been assisting children with special needs in the Madison County School District since 1994. He is currently providing direct services to children at Madison Avenue Upper Elementary in addition to consultations to teachers, therapists and students at schools throughout the remainder of the district.

"In order for a child to receive occupational therapy in a school system, they have to have a ruling of special education," said Giroux. "That could be something as complex as cerebral palsy or spinal bifida, or it could be something as mild as dyslexia or attention deficit disorder, what we call processing issues — auditory and visual processing."

The demand for occupational therapists in the school system has grown since Giroux began.

"When I started working in 1994, I worked six to eight hours a week," said Giroux. "I saw every child who needed occupational therapy in Madison County in that six to eight hours a week."

Now Giroux and another therapist work together in just one school while four other therapists cover the rest of the county.

Giroux said that he sees many more children on the autism spectrum than he did when he began. For many of his high-functioning autistic patients, communication is the biggest challenge. With fine motor delays handwriting is extremely difficult.

"From an OT standpoint, these students are so fun to work with because they have such high-functioning intellectual brains," said Giroux. "But we are asking 'How are we going to get around this difficulty with handwriting in order to complete classroom assignments?'"

In the end, the primary goal of an occupational therapist is to help the child function in the real world, despite the developmental or physical challenges they may face.

"I'm not there to fix the child. I'm there to take that child the way they are and help them to function and be successful in the classroom environment."