Study finds higher COVID-19 death rates for American Indians

While American Indians make up less than 1 percent of Mississippi’s population, they made up 4.5 percent of recorded COVID-19 mortalities by July 2020.

New research from the University of Mississippi Medical Center looks to explain why that’s the case. The study, published online March 30 in JAMA Network Open, found that American Indian COVID-19 patients were more likely to die in the hospital from the disease than White or Black patients even after accounting for pre-existing health conditions.

Leslie Musshafen, executive director of research at UMMC, led the study.

“I started to hear from physicians that they were seeing significantly worse outcomes among American Indian patients infected with the virus,” Musshafen said. “Without exception, greater comorbidity burdens among Native populations were suggested to explain the phenomenon.”

Musshafen, who will graduate with a PhD in population health science next month from the John D. Bower School of Population Health, decided to test that idea as part of her dissertation.

She and her colleagues used health records from the Mississippi State Department of Health’s Inpatient Outpatient Data System. They found 18,000 COVID-19 patients admitted to 103 Mississippi hospitals in 2020. They used the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (ECI) to estimate a patient’s risk of death. The index includes 31 health conditions or risk factors, including heart disease, cancer and diabetes. Research from throughout the pandemic shows that these conditions and others can make COVID-19 more severe or increase an individual’s chance of death.

“The higher the score, the higher the odds of death with COVID-19,” she said.

They also sorted patients into groups based on race. Black and White patients each made up about 49 percent of the study sample, while American Indian or Alaskan Native, or AIAN, patients made up 1 percent.

They found that on average, AIAN patients had lower ECI scores than both Black and White patients.

“This means that we would expect, overall, for Native Americans to have lower mortality rates,” Musshafen said.

However, that’s not what the study found. Among all included COVID-19 patients, 29.8 percent of AIAN patients died, compared to 14.6 percent of White patients and 13.6 percent of Black patients.

They also compared smaller groups with similar comorbidity risk scores. At each level, AIAN patients were more likely to die in the hospital than White or Black patients.

AIAN patients also had the longest average hospital stay at 9.9 days, compared to 8 days for Black patients and 7.8 for White patients.

The paper follows up on an initial study, which showed similar trends in UMMC patients alone using a smaller set of risk factors.

“UMMC is the only level 1 hospital in the state and is not particularly close to any of Mississippi’s Choctaw communities,” Musshafen said. “We wondered if our outcomes were skewed because the COVID-19 patients we admitted at the time were likely some of the sickest of the sick. We conducted the larger, statewide study to find if the results would hold true.”

Mississippi’s only federally recognized tribe is the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, primarily based in eight communities in the eastern part of the state.

Musshafen said issues of race and geography that create a “double disparity” may impact rates of death. She and co-authors note a history of discrimination and marginalization of indigenous people. In addition, rural populations of any race tend to have worse health outcomes, in part due to fewer and farther-away health facilities.

“All eight Choctaw communities are in rural and medically-underserved areas,” Musshafen said.

Dr. Loretta Christensen and Shawnell Damon of the Indian Health Service published an invited commentary on the paper. They say that the findings are an “important” part of understanding the effects of COVID-19 on AIAN populations early in the pandemic. They also note that successful public health outreach may help address the disparity.

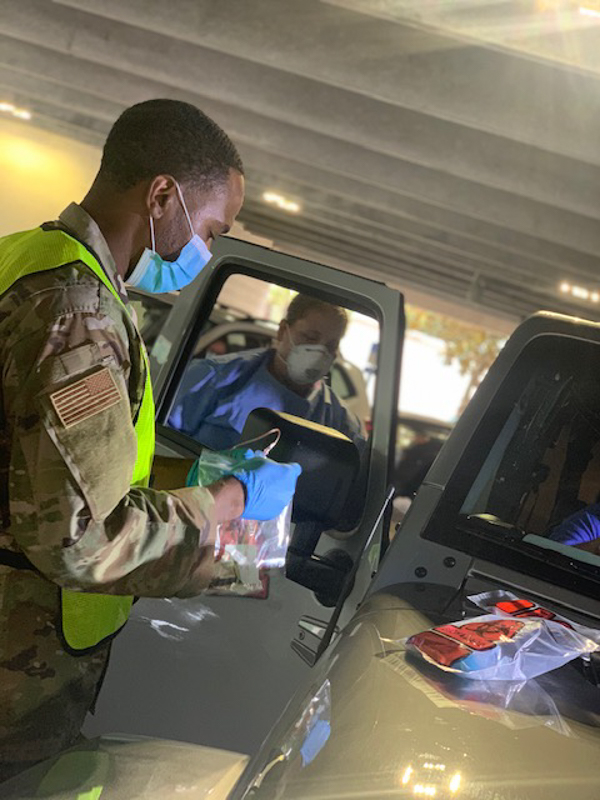

“The high administration rate of the COVID-19 vaccine among American Indian and Alaska Native individuals suggests that equitable access to treatment may lead to positive health outcomes in this population,” they wrote. “There has been a decrease in mortality among American Indian and Alaska Native individuals owing to the accessibility of the COVID-19 vaccines as well as the availability of COVID-19 therapeutic treatments.”

Musshafen chose to study effects of COVID-19 among American Indians in her dissertation, in part, because of existing health research gaps in the population even pre-pandemic. To help guide the process, she chose a mentor who knows COVID-19 in Mississippi perhaps better than anyone: Dr. Thomas Dobbs, MSDH’s state health officer and an associate professor of population health science at UMMC.

“He graciously agreed to serve on my dissertation committee and then to become chair,” she said. Even during some of the busiest weeks of the pandemic, “we would have weekly calls and Dr. Dobbs would ask, ‘What can I do to help you?’”

When Musshafen graduates next month, she will be part of the SOPH’s first group of students to complete their PhDs.

For 14 years, she has worked on the “other side of research,” managing administrative aspects on the Medical Center’s discovery enterprise. When she decided to pursue a PhD and conduct her own research, the SOPH’s program provided the flexibility to complete her degree and continue her career in the Office of the Associate Vice Chancellor for Research.

“I want to make a positive impact on health disparities in our state and contribute to improving the health of Mississippians,” she said.

The study’s co-authors include Dobbs, Dr. Seth Lirette, assistant professor of data science, Dr. Richard Summers, associate vice chancellor for research, and Dr. Caroline Compretta, associate professor of preventive medicine, all of UMMC; and Lamees El-Sadek, MSDH epidemiologist.