Praise be: Matemavi’s journey fired with passion and purpose

Trying to tell Dr. Praise Matemavi’s story in anything smaller than an encyclopedia is like pouring Niagara Falls into a shoe.

The life of the young assistant professor of surgery at the University of Mississippi Medical Center is a torrent of striking details; a lot will have to be left out. But what?

The flamingo-colored shoes she wears in memory of her mother? The 350-page book she wrote in under four months? The life she knew in Africa until she was 14? The unplanned pregnancy, the abusive marriage, the struggle with self-doubt?

Certainly, you don’t leave out the man from Zimbabwe, Titus Matemavi, the Seventh-day Adventist minister who named his second child Praise, younger sister of Faith, and who, when Praise was 10, placed in her hands a book that set her feet on a journey toward one of medicine’s most demanding careers.

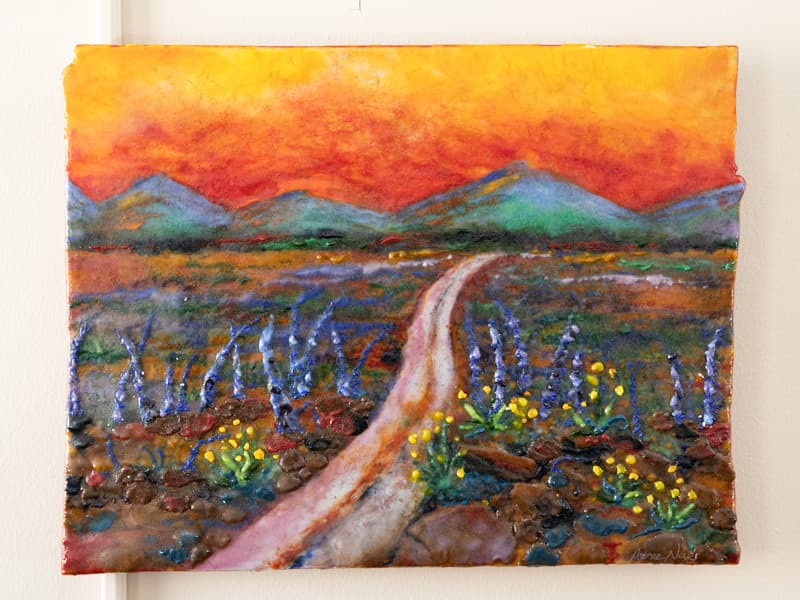

“I read that book in one night,” said Matemavi, seated in an office decorated with framed tributes to her triumphs as one of the rarest of the rare: a black female transplant surgeon in America. Alongside those honors hangs a painting she calls “The Journey.”

The landscape of a twisting path coursing to distant mountains is a reward from her former colleagues for finishing her fellowship last year at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. The book, an engine of inspiration, had helped propel her there, to Omaha.

“It was 'Gifted Hands: The Ben Carson Story', Matemavi said. Her father gave it to her shortly after she discovered the existence of what must have sounded, to a 10-year-old’s ears, like a miracle: Surgery that was repairing children’s damaged hearts.

That was what she was going to do, she decided. “Reading how [Carson] had gone on, from being a child growing up in the ghetto, to becoming a doctor was powerful,” she said. “This showed me that even I could do it.”

But her parents decided she couldn’t do it in Zimbabwe. And, so began the journey.

The biggest fear

Rose Matemavi did not see her younger daughter finish her surgery training at New York Presbyterian Queens Hospital; not quite. Two months before Praise graduated, Rose died.

Pink is the color of breast cancer awareness, and Matemavi decided to wear shoes covered in it, in memory of her prayer warrior, the woman she texted before every surgery to ask for prayer’s protection in the OR.

Prayer, and hope, had led Titus and Rose Matemavi, a nurse, to move, in their forties, from Zimbabwe to Berrien Springs, a Seventh-day Adventist community in Michigan, believing that America was a better setting for their daughter’s dream.

That dream is in writing. In East Lansing, during a visit to the campus of Michigan State University, Faith took a picture of Praise in front of the administration building. On the back of the photo, are the words of Praise: “This is where I will come for medical school someday.” She was 14, and she was right.

“My parents didn’t put any limits on what I could do,” she said. “They believed so much in me.”

And they expected much of her. But, years later, there was one thing Matemavi could not do for her mother during the weeks and months when both knew she was dying of cancer.

“‘Child, if you want to cry, get out,’” her mother told her. But during this time, Matemavi thought like a doctor and cried like a daughter.

It was the most painful experience of her life, she said. More heartbreaking than the time she, 18 and unmarried, had to tell her father she was pregnant.

More painful than having to marry a man she didn’t love. More dreadful even than the violence by his hand; she dealt with that, too.

“I thought if I stayed in that relationship I would end up dead,” she said. “I realized I had to do whatever I could to survive. It shaped the way I viewed life – that I was not a victim, that I would choose the way I came out, that I would not let it define who I was going to be.

“It taught me to fight for the life I want.” And to fight for her children; by then, she had two. So she left him, afraid to go, but more afraid not to.

“That was the biggest fear I had to conquer,” she said. “For you to grow, you have to have fear. Then you get past it.”

‘Our ancestors’ wildest dreams’

When she came across the story of Dr. Sherilyn Gordon-Burroughs, some of that fear must have crept back in. Matemavi devotes the first chapter of her book to her, honoring a woman she never met and never will.

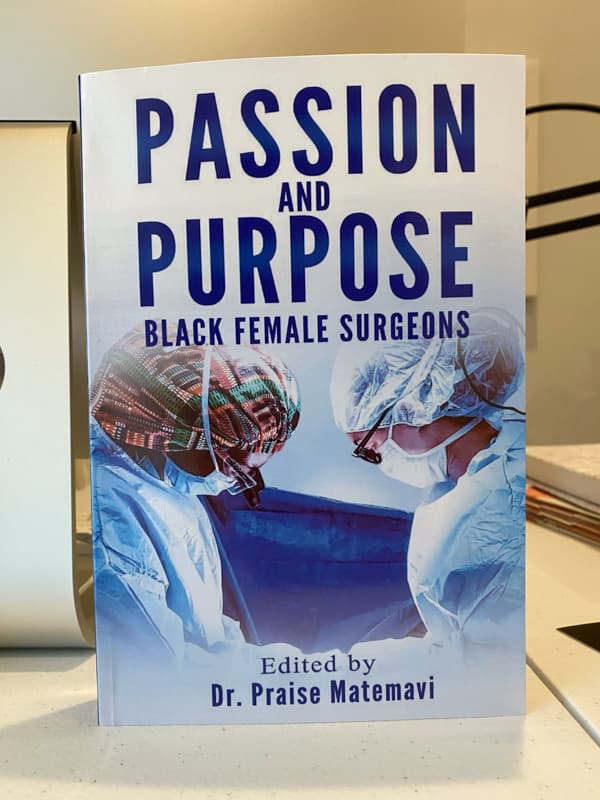

There are more than six dozen other women described in that book, Passion and Purpose: Black Female Surgeons, but it’s unlikely any remind Matemavi of herself more than Gordon-Burroughs.

Like Matemavi, she was a child of immigrant parents, a Seventh-day Adventist and odds-beating force of nature. Unlike Matemavi, she didn’t survive her abusive marriage.

The idea for this book came to Matemavi late last year. “At a lot of places I’ve been, there was no one else who looked like me and who was doing what I was doing,” she said.

“Since I didn’t have that reference, I decided to provide it for others who come after me. I wrote it for young people to know that, whatever dream they have, it’s possible.”

This past spring, during pandemic-imposed seclusion, “I had more time than I knew what to do with,” Matemavi said. “Basically, I had no weekends for two-and-a-half months. The book is all I worked on. The women in it are incredible. They inspired me.”

They represent more than two dozen countries, many in Africa. They include UMMC faculty members Dr. Shuntae Batson, Dr. Keisha Bell Catchings and Dr. Gina Jefferson, along with Dr. Amber Hardeman, a former UMMC surgery resident now at Tulane University.

“We are certainly our ancestors’ wildest dreams come true,” Matemavi wrote in the book’s introduction.

For the chapter on Gordon-Burroughs, she interviewed the surgeon’s parents; they said their daughter never complained about her home life. This, too, must have resonated with Matemavi.

“You feel like no one else will understand, so you don’t say anything,” she said. “I was ashamed.” In her own experience, Matemavi was 21 at the time and had two small children.

“But I also feel like it made me very independent,” she said. “When I left, I knew I had to become the best mom I could be, and the best at whatever I do.”

Affording the best was a different matter. Because she was not a naturalized citizen at the time, Matemavi wasn’t eligible for student loans at a university, she said. She was able to get enough scholarships, though, to cover her tuition at a community college, where she earned her Associate Degree in nursing.

For three years she earned her living as a cardiac nurse in South Bend, Indiana, a single mother of two. Eventually, she became a citizen of the United States. But there was still one obstacle left for the aspiring medical student. No, not the MCAT, or admissions test. Matemavi had the scores to get into medical school. What she didn’t have was a bachelor’s degree.

“All these medical schools require one,” she said. She had one year to earn the 60 credits she needed; one year to be on schedule for her self-imposed goal: Finishing medical school by the time she was 29. And she did it.

She did it by taking 30 credits one semester, and another 30 the next. She did it by attending class all day and into the night, leaving her kids with a babysitter. She did it while working the 3 to 11 shift on Fridays, spending time with her kids at church on Saturdays, then working a double shift on the weekend.

She did it at Sienna Heights University in Michigan, where an academic adviser had told her it would not be possible.

On June 24, 2006, she entered the Michigan State College of Osteopathic Medicine at the university she picked when she was 14.

“I started at Michigan State 10 years later, to the month,” she said. It was her birthday.

The miracle

Unlike her choice of medical school, her choice of a career – heart surgery – did not endure. Ironically, it was a cardio-thoracic surgeon who helped convert her to another cause.

“He had seen me reading 'Walk on Water' when I was a medical student,” Matemavi said.

Written by Dr. Michael Ruhlman, the book is subtitled “The Miracle of Saving Children’s Lives.” The surgeon told Matemavi about another miracle: pediatric liver transplant surgery.

“He described as “‘technically challenging and beautiful in its own right,’” Matemavi said. And that’s why she became, her research says, one of only 10 black female transplants surgeons in the country.

As it turned out, Matemavi said, the surgeon was right. Over the years, she has discovered the redemptive beauty of abdominal transplant surgery in general and kidney transplants in particular.

“It gives me joy to see someone who has been on dialysis for years and now is now able to go back to work and take care of their families,” she said.

The surgeon at Michigan State also helped shape Matemavi’s geographical destiny. “He knew a surgeon at the University of Nebraska, Dr. Alan Langnas, who did this type of surgery,” Matemavi said.

“So you can imagine how excited I was when I was accepted there for training.”

That acceptance followed her surgery residency in New York. And a second divorce. In medical school, she had married a fellow student, but during her residency, the marriage became a victim of her exhausting schedule.

It was one of several blows she took as a resident. Another was her mother’s death. Still another was bias directed at her – not her race, but her gender.

“‘Girls do not belong in an operating room,’” she heard an attending physician say. Others said her skills or temperament were better suited to other, less demanding types of surgery, not transplant.

“I wondered if I was good enough,” she said.

There is no self-doubt like the self-doubt of a perfectionist, and no sadness like a daughter’s grief. In each case, the words of others intervened. They were the words of her mentors and teachers, including Dr. Howard Tiszenkel. Today, Matemavi wonders if he told every intern that he or she was destined for “greatness,” but it doesn’t matter. Because that’s what she needed to hear.

And when her mother died, there were the words she heard often from Titus Matemavi, about a God who is just and faithful and perfect and does no wrong. Dad and Deuteronomy pulled her through.

Snowless in Jackson

Dr. Wendy Grant was one of the surgeons who trained Matemavi in Omaha. There, Matemavi did her fellowship in abdominal transplant surgery and hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery. Sometimes Grant still has trouble finding the right word to describe her former pupil, even now, a couple of years later.

“She has … I don’t know what it is,” Grant said. “Even when things are really hard, she is so generous. She made it really easy to train her.”

Grant, the Alton S. Wong, M.D. Distinguished Professor in Surgery at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, has guided around 20 transplant surgeons. None, if any, was able to make than others on their surgical teams feel more wanted or welcome than Matemavi could, she said.

“She is one of a kind. A great mom, friend and sister. You think, ‘How can someone really do all this stuff?’ Well, she does it. We wish she was still in Nebraska. Fortunately for you, Mississippi has her.”

Grant can thank herself for that, in part. “I knew a couple of the surgeons at [UMMC],” she said. “I thought she would be great for them, and it would be a great place to start. I asked if they were looking for someone.”

For her part, Matemavi was looking for two things: a place that needed her and one with “no snow,” she said. She found both, more or less, in occasionally snow-dusted Jackson.

At UMMC, which she joined in 2019, she has performed mostly kidney transplants, a need for many African Americans, she said.

“She’s a great surgeon and partner,” said Dr. Chris Anderson, the James D. Hardy Professor and Chair of the Department of Surgery at UMMC. “She has made our team better.

“She has a passion for all things transplant and all the pieces that are part of it,” said Anderson, who is the surgical director for liver transplant and kidney transplant, and medical director of abdominal transplant.

“The patients love her. The transplant nurses and staff love her. OR loves her.

“The theme of her book and the reason she wrote it are in line with her personal values. I’m very proud that she did it, and proud of what she’s going to do in the future.”

Matemavi plans to spend the rest of that future with Ryan Tiemeyer, a dialysis nurse she met in Omaha, who “spoils me every day,” she said. Matemavi now has two biological children, three stepchildren and one happy marriage.

In heaven’s name

One look at her and people see someone without secrets, someone as vivid and honest as the flamingo-colored shoes hugging her feet.

She greets the curious with a voice half-welcoming, half-shy, as if she’s not sure people want to hear her story, but pretty sure they should.

Because – and here’s the takeaway – for every heartbreak that inflamed her life, for every tragedy and disappointment, along came a windfall to tamp it down and tame it.

She knows the grief of watching a loved one die, and the joy of seeing a dream come to life; the pain of domestic abuse, and the rewards of a caring family.

But, until a few weeks ago, there was one thing about herself she couldn’t tell you, because she didn’t know: How she got her name.

The one person who did know now lives in California, so she sent him a text. “… I was so sick between 1973-August 1975,” he wrote her back. “People didn’t think I was going to live, get married and have children.

“Progression of the names: Faith - it is by Faith that the Lord blessed me with my first child and Praise the Lord for my second child!!!”