Sex, drugs and brains: probing the origins of addiction

Published in News Stories on December 15, 2016

Absence makes the heart grow fonder, but it also makes the brain grow vulnerable.

In the study featured in the September 21 issue of the Journal of Neuroscience, UMMC researchers show how removing their mates may make rats more susceptible to drug abuse.

It's the latest published finding from the lab of Dr. Lique Coolen, who studies the neurological basis of behavior, particularly as it relates to drugs of abuse.

“Some people try drugs once or twice and they have no problems. Others try drugs once or twice and they become addicted,” said Coolen, professor of physiology and biophysics and the paper's senior author.

While there are several factors that may determine who is most at-risk for drug abuse in humans, strong social networks appear to have a protective effect, Coolen says. The more rewarding relationships a person has - family, friendships and a spouse - the better the buffer. The goal of the study was to learn what happens in the brain when that buffer breaks down.

While “rats don't have friends” in the manner humans do, Coolen said, they do have another immensely rewarding social behavior: sex.

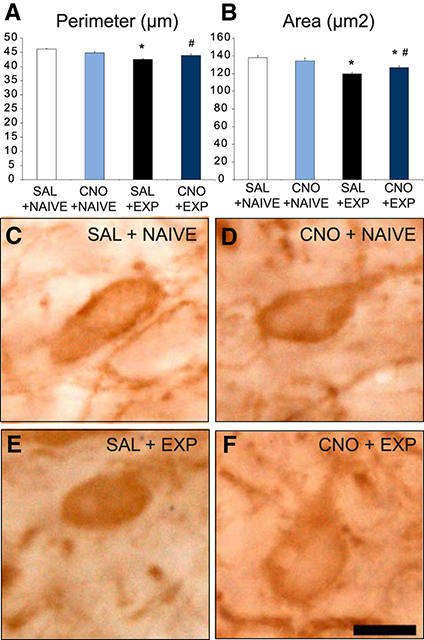

After drug exposure, rats with sexual experience (SAL + EXP)have smaller VTA dopamine cells, shown in darker orange, than inexperienced rats (NAIVE) and experienced rats with the dopamine signaling shut off (CNO + EXP).

During the experiment, male rats spent five days with a female, followed by a period of forced abstinence. They then had four sessions in a multi-chamber cage. In the first, the males freely explored the rooms. In the second and third, they received a low dose of amphetamine while constrained to one of the chambers. In the fourth session, the males could explore again.

Except the rats didn't explore their cages this time. Rather, they went to the chamber where they received the drug, looking for more.

“When an animal experiences a reward, but then the reward is no longer in place, they become more vulnerable” to other stimuli, Coolen said. The reason, she says, is a process called cross-sensitization. Experiences like sex can make the brain more responsive to new experiences that work in similar ways.

“Addiction is a very complicated disorder,” said Dr. Nikki Beloate, a 2016 graduate of UMMC's Ph.D. program in neuroscience and the paper's first author, “We studied just one part of it.”

That part, she said, is cross-sensitization in a brain region called the ventral tegmental area, or VTA.

Beloate

“The system is in place for natural rewards such as food and sex,” said Beloate, who now studies drugs of abuse as a postdoctoral fellow at the Medical University of South Carolina “However, drugs can use this system as well.”

Drugs such as amphetamine excite cells in the VTA that produce dopamine, the chemical that reinforces our desire for natural rewards. Coolen, Beloate and their colleagues observed that the VTA dopamine cells were smaller in the sex-deprived rats, showing a potential cause for the change in behavior.

To show this was the case, Beloate used genetic tools to turn off the VTA signaling in one group of rats, blocking the dopamine signal. They were still able to mate, but did not develop a vulnerability to amphetamines. Furthermore, their neurons did not shrink and change, showing that sex in itself does not directly make the rats sensitive to drugs. Rather, the dopamine release triggered by this natural reward mediates cross-sensitization.

According to the article, “Activation of dopamine neurons during sexual behavior results in long-lasting neural alterations that, in turn, influence responses to drugs of abuse.”

While Coolen emphasizes that studying behavior, not treatment, is the focus of the research, studying the biology and behavior of addiction does provides a basis for other treatment-oriented projects. This is especially important for research on stimulants like amphetamine, as there are no FDA-approved pharmaceutical treatments for these addictions, said Dr. James Rowlett, professor of psychiatry and human behavior.

“It's really hard to identify [pharmaceutical] targets that will not interfere with the natural reward pathways,” said Rowlett, who also studies drug abuse and dependence. “Basic research like this is crucial to understanding, designing and targeting treatments.”

Co-authors on the study include Dr. Ian Webb, UMMC assistant professor of neurobiology and anatomical sciences, and researchers at the University Medical Center of Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Photos

| High Resolution Medium Resolution Low Resolution |

| High Resolution Medium Resolution Low Resolution |

| High Resolution Medium Resolution Low Resolution |