UMMC stands ready to care for victims of Ebola and other communicable diseases

Although much attention has been placed on a highly specialized isolation unit at Atlanta’s Emory University Hospital, where two Americans suffering from the deadly Ebola virus are being treated, major medical centers also can care for Ebola patients, health experts say.

That includes the University of Mississippi Medical Center, the state’s only Level 1 trauma center that houses significant infectious medicine expertise and daily treats and isolates dozens of patients with highly contagious diseases.“Any advanced hospital in the U.S., any hospital with an intensive care unit, has the capacity to isolate patients,” Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the Atlanta-based Centers for Disease Control, told national media last week.

UMMC routinely treats communicable diseases such as TB or HIV. That expertise and training extends to viruses extremely rare to this country, such as Ebola. “Our job at UMMC is to take care of our staff, our patients and our visitors,” said Dr. Elham Ghonim, UMMC’s director of infection prevention whose Ph.D. is in clinical health sciences.

“We see the sickest population in Mississippi. We deal with multiple infectious diseases every day, and we perform the highest-risk procedures in the state. Our laboratories work with specimens and perform tests that might not be done at other hospitals in the state.”

Said Dr. Rathel “Skip” Nolan, UMMC’s medical director of infection prevention and director of infectious diseases: “I’d be very surprised if we saw a case at UMMC, but if we did, we know how to handle it, and there would be a half-dozen people with us from the CDC, probably within about six hours.”

National health experts say the chance of a U.S. outbreak of Ebola, now raging in several west African countries with the death toll Thursday morning at a minimum 932, is slim. At UMMC, protocols are in place to safely isolate patients with communicable diseases and at the same time protect those providing care, Ghonim said.

The hospital stood ready to isolate and treat patients with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus, a sometimes deadly illness first reported in 2012 in Saudi Arabia. No patients were treated, but “we had a large number of students and staff from the Middle East who were traveling back and forth,” said Ghonim, who is from Egypt.

To contract Ebola, a person must come in direct contact with an infected person’s blood, organs or other bodily secretions that can include sweat, vomit, urine or feces. It’s not airborne through coughing or sneezing. The worst symptoms are multiple organ failure and unexplained internal bleeding. Those stricken can have sudden high fever, intense weakness, muscle pain, headaches, vomiting and diarrhea.

Health-care providers in UMMC’s Emergency Department have received information on the outbreak, including instruction on how to care for patients and identify possible Ebola symptoms, said Dr. Alan Jones, professor and chairman of the Department of Emergency Medicine. Patients will be questioned about their travel and who they’ve had contact with, Ghonim said. “If it’s suspected they could have Ebola, they will be isolated right away,” she said.

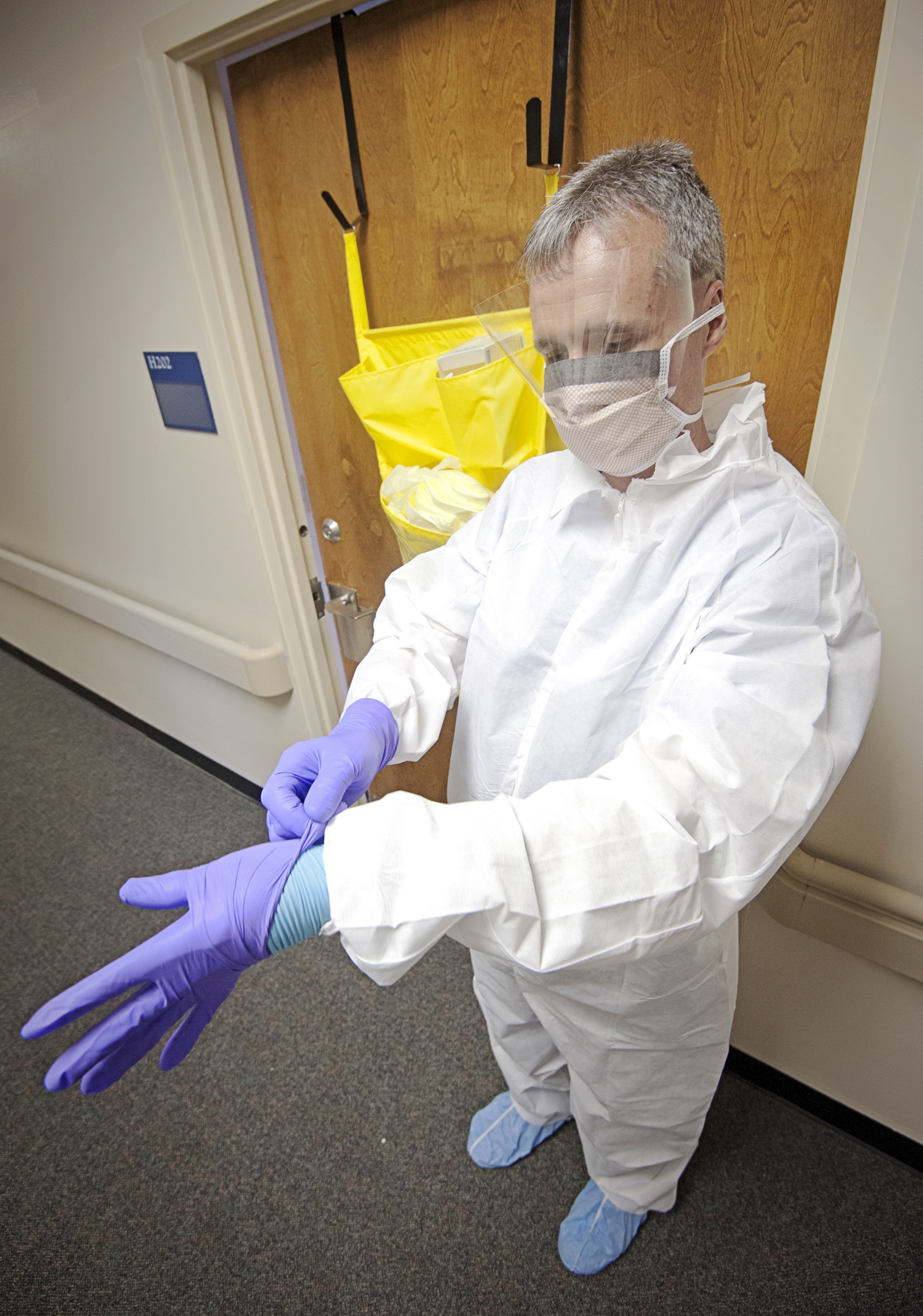

UMMC employees giving direct care to patients with confirmed or suspected cases will be completely covered with what’s called personal protective equipment, or PPE, Ghonim said. That always includes a face shield, goggles, gloves, a gown, and head and leg coverings. A “bunny suit” similar to a hazmat suit also can be worn, she said.

The contagious nature of body fluids “is why you will be covered from head to toe when you enter their room,” Ghonim said. “Isolation will be very strict, and visitation will be very limited.”

Caring for a patient with Ebola would be voluntary, Nolan said. A log would be kept of the few staff members allowed in the patient’s room, and equipment or instruments used would be cleaned with specific solutions that kill the worst infections, Ghonim said. Also, patients may be placed in negative pressure rooms designed to draw contaminated air outdoors and away from employees and the patient.

Hand washing – already greatly emphasized for all employees – would be even more critical, Ghonim said. Miss hand hygiene one time, she said, and it could make the difference between protection and infection.

A person with Ebola first becomes contagious with fever, but it can take up to 21 days for symptoms to show, she said. On Monday, a man who recently returned from west Africa showed up at a New York City hospital with symptoms consistent with Ebola. He was placed in isolation seven minutes after arriving, hospital officials said, although officials say testing likely will show he doesn’t have the disease. That came on the heels of an Ebola scare with a patient at each of two other New York City hospitals.

UMMC health-care providers exposed to a patient with possible Ebola ”will be monitored for 21 days, and their temperature will be taken twice a day,” Ghonim said. “Before now, Ebola was not a risk factor for us here in the United States. But now, health-care workers and other travelers are coming back and forth from outside the country.”

There’s no vaccine, although one is in the works, and Ebola can have up to a 90 percent mortality rate. The only treatment can include intravenous fluids, blood products and being put on a respirator or dialysis, depending on the extent and duration of the illness, which can last two or three weeks. Those in contact with the dead body of a victim are still at risk – a major reason Ebola spreads in west Africa, Ghonim said.

UMMC maintains a full-service travel and vaccination clinic for Mississippians planning trips to locations including Africa, Asia and South America. But for now, Ghonim has a piece of advice for anyone considering overseas travel.

“Limit your travel to this part of the world. Every week, the number of Ebola deaths is increasing,” she said.