Prediction tool helps control pressure injuries

Published in News Stories on September 26, 2016

When a hospital patient develops a single pressure injury, it costs the facility about $44,000 - and costs the patient pain, days or weeks of healing time, and an added risk of infection.

A new analytics tool the University of Mississippi Medical Center will begin using in October, however, will help prevent ulcers from forming by predicting when and how they would likely occur.

The predictive analytics program, developed in partnership with a third-party company, crunches data every night, for every person who's a patient at the state's only academic medical center. The program analyzes a menu of clinical and demographic information specific to each patient - more than 4,000 variables, including the patient's zip code.

“This is the most exciting thing I've done here in 20 years,” said Keith Hodges, a registered nurse and the Medical Center's clinical intelligence manager. “This is the future of health care. We're applying these analytics to all patients, no matter their perceived risk.”

Hodges

A pressure injury - called pressure ulcers or bedsores by many - occurs when there's pressure on a specific area of the body for a prolonged period. It usually occurs in people who stay still for a long time, such as those who are bedridden from chronic illness or serious injuries.

Pressure injuries are defined by stages, with the least severe being a reddened area that often forms over a bony prominence. More severe pressure injuries can be either shallow or deep, exposing cartilage, bone, tendon or muscle. In some cases, a pressure injury can contain dead tissue that must be removed before it can heal.

Hospitals with high rates of pressure ulcers are financially penalized by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, giving all facilities incentive to keep down the rate.

UMMC also uses predictive analytics to forecast which patients are at highest risk for suffering a heart attack and when. That mathematical analysis considers environmental data, some also based on a patient's zip code, whether he has a telephone or how far he lives from a pharmacy, to better identify his health risks.

Showalter

Dr. John Showalter, associate professor of family medicine and the Medical Center's chief health information officer, agrees with Hodges that predictive analytics “is the future direction” of medicine.

“We need to get our limited resources to the right people,” he said. “We're in the process of developing hospital readmissions predictions, and we're looking at our ambulatory population to identify 100 to 200 of our patients who are most at risk of getting sick over the next year. Our plan would be to get them plugged into primary care or internal medicine for a medical home.”

UMMC has historically used the Braden Risk Assessment Scale for predicting the risk of developing pressure injuries, but it considers only subjective factors, such as a patient's mobility or exposure to moisture through incontinence. “We wanted something that looked at more than that,” Hodges said.

The answer, he said: Deep machine learning.

“We worked with a third-party company using predictive analytics,” Hodges said. “We take much of the data in a patient's electronic record and securely send it to the company's analytical engine. They combine it with some publicly available data that we don't have access to - socioeconomic data that includes, for example, census data.

“You take that into account, and you see what patients here who have a pressure injury have in common. We take those common factors and apply them to all the patients in the hospital every midnight and use this to predict their risk. The machine learns every day, because it gets new information every night.”

When a patient's zip code is factored in, the computer takes into consideration the extra four digits at the end of the code, narrowing the patient's physical residence down to 10 houses on his street, or five on either side. “You can assume the household incomes are close to the same, and the kids all go to the same school district. They all live the same distance from the nearest hospital. We can make some assumptions, and it weighs into their risk,” Hodges said.

If the patient's treatment has changed, the machine learns it, Hodges said. If a patient is moved from a floor to the ICU, the machine knows. “It learns our patient population,” he said. “It identifies patients who we might not normally pick up on, not just those with the obvious signs.”

Better prevention and prediction of pressure injuries help floor staff wisely use equipment and precious people resources. “A lot of the interventions we're doing are very costly,” Hodges said. “This tells us who needs a specialty bed. If you have 32 patients, you could walk around all day turning them. You need to know who needs to be turned constantly, without fail. We can concentrate our resources to the patients who truly need them.”

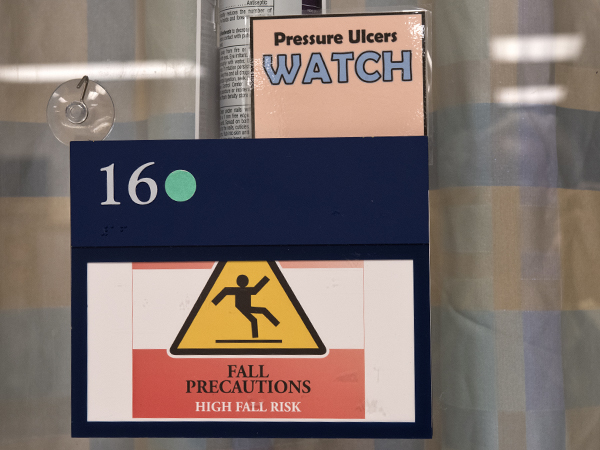

The doors of Medical Center patients in the Conerly Critical Care Hospital, many who are bedbound for a long period of time, often carry signs alerting staff to pressure ulcer risk.

The Medical Center has multiple interventions to prevent pressure injuries, said Amy Taylor, a nurse educator in the Medical Intensive Care Unit who also serves on UMMC's pressure ulcer prevention task force.

“Every bed in the hospital uses technology for the purposes of redistributing pressure, and most are designed to manage microclimate and moisture to counter the effects of incontinence,” she said. The Medical Center promotes limited use of layers of linens in an effort to maximize benefits of specialty beds, she said.

Nurses also employ wedge pillows for turning patients in bed, boots that support the calf and heel, dry pads for wicking moisture away from patients to protect their skin, and moldable pillows that can redistribute and offset pressure areas on the neck, head and back. “We elevate their ankles and feet with pillows, and we caution against the use of blankets and towels or anything that is not specific for pressure redistribution,” Taylor said.

Use of predictive analytics for pressure ulcer prediction and prevention involves a learning curve for front-line caregivers, Hodges said. “We were taught as nurses that you put a draw sheet and a pink pad on a bed,” Hodges said. “Now, we're pushing stripping the bed down and only using linens. Let's look at what we are doing and make sure we don't cause harm.”

Dollars saved, Hodges and Showalter say, benefit both the patient and the hospital.

“Just the cost savings from pressure ulcers is well over three times what we spend to do the analytics,” Showalter said. “You have a 300 percent return on the analytics, and that makes predictive analytics free for our other programs."

Photos

| High Resolution Medium Resolution Low Resolution |

| High Resolution Medium Resolution Low Resolution |

| High Resolution Medium Resolution Low Resolution |

| $2 million grant to fund communication, medical skills training for ‘first hands’ High Resolution Medium Resolution Low Resolution |