Hand hygiene: every time, all the time!

Published in News Stories on September 17, 2015

What's the quickest and easiest step University of Mississippi Medical Center employees can take to protect patients from infections?

Wash their hands, every time, with every patient contact.

It's that simple - yet it's a step that's skipped about half of the time by Medical Center employees who have direct contact with a patient, such as a doctor or floor nurse, or indirect contact, such as members of housekeeping.

Henderson

In-house observers during the month of July began collecting data that today shows a 55 percent baseline compliance, meaning employees who should be washing their hands while taking care of patients are only doing it 55 percent of the time. "That's not good enough," said Dr. Michael Henderson, UMMC's chief medical officer and sponsor of the team that is finding solutions to increase hand-washing rates. "We are serious about patient safety, and we're serious about a change in culture."

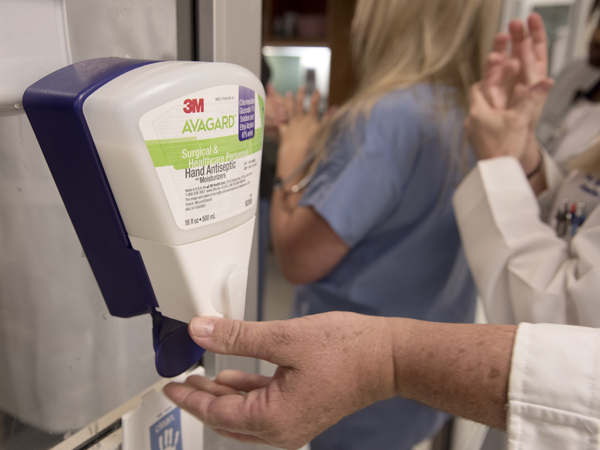

That's the mantra of "Hand Hygiene: Every Time, All the Time!" It's an initiative kicking off this week that encompasses all Medical Center facilities. Washing hands, or foaming in and out when entering and exiting a patient room or treatment area, is the single most important defense against hospital-acquired infections.

"All of us who work here are caregivers, and as such need to understand current performance and recognize we can improve," Henderson said. "Hand hygiene is an opportunity no one can argue about being a great way to improve patient outcomes."

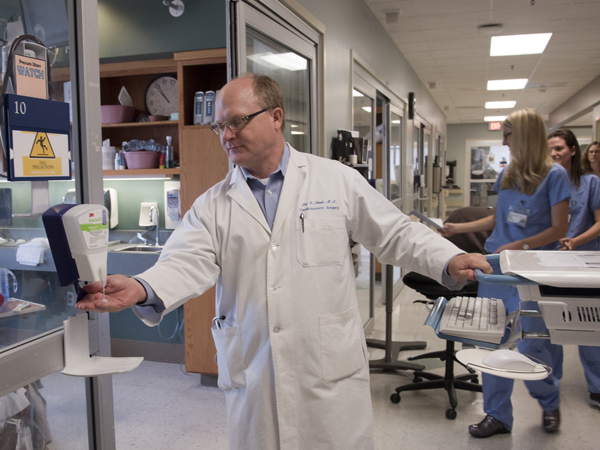

UMMC cardiothoracic surgeon Dr. Jay Shake takes time to foam his hands with sanitizer before entering a patient room on the cardiovascular intensive care unit.

From July 6-August 5, about 80 volunteers representing 22 departments began a 12-week process to collect data on appropriate hand washing. Secretly observing only in direct patient care areas, they used a special data collection tool to gather information for a baseline percentage of who is washing and who's not. They built the observations into their daily shift, but in a manner that would not detract from their job responsibilities.

After 3,741 observations, the baseline was revealed: 55 percent of the time, those who should have washed their hands did it, which is not unusual when accurate baseline data is collected.

Breazeale

"Some employees think if they go into a patient room and don't touch that patient, they don't have to wash their hands. That's wrong," said Amanda Breazeale, UMMC manager of performance improvement.

The stakes are high. Hospital-acquired infections can be deadly and include the staph infection known as MRSA, or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; urinary tract infections caused during catheterization; bloodstream infections that occur during the use of central intravenous lines; and clostridium difficile, also called C. difficile, a bacterium that can cause symptoms ranging from diarrhea to colon inflammations. Surgical site infections, bedsores or ulcers, and pneumonia also can result from hygiene shortcomings on the part of caregivers.

Nationwide, such infections result in thousands of deaths annually and billions of dollars in added health-care system costs. And it can erode patient and family confidence that UMMC - or any hospital - is a safe place to receive care.

"We know that the majority of bacterial pathogens that infect someone in the hospital are carried on the hands of health-care workers," said Dr. Skip Nolan, professor of infectious diseases and director of the Division of Infectious Diseases.

Nolan

"You touch a patient, and they have germs on their skin. You don't do proper hand hygiene, and then you go into another patient's room and touch them, and you transmit that bacteria to them," Nolan said. "Since germs are microscopic, people just really don't think they exist. If you don't do hand hygiene and follow isolation guidelines, there may be no visible evidence you've done something wrong, and that's why people get complacent.

"But people have adverse outcomes and can die from this. If people acquire MRSA in the hospital, it's virtually always because of a lack of hand hygiene. The only way we can stop the spread of these things is to get people to wash their hands."

The Medical Center is embracing the experience of the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare, an organization on a mission to solve the most critical safety and quality problems facing health-care providers. The Joint Commission advocates a systematic approach to analyze specific breakdowns in care and discover their underlying causes to develop targeted solutions that solve these complex problems.

"This isn't just about hand hygiene, but a different approach that calls for elements of culture change," Henderson said. "Part of the culture change we want to achieve is for employees to understand the issues, help each other come up with solutions, and be accountable and responsible for hand hygiene."

How the Medical Center's program is working:

- Monthly data collected on hand-washing rates will be shared with employees. During the initial month-long observation, the baseline ran 55 percent, with the low for a particular day being 45 percent and the high being 80 percent, Breazeale said. The percentages show variability by locations. "We must all work to be to top-level performance," Henderson said.

- "Just in Time" coaches, also Medical Center employee volunteers, are "asking employees who aren't washing their hands what the barriers are," Breazeale said. "We're looking for non-observable factors so that we can find solutions."

Some of the hand sanitizer gels used on the cardiovascular intensive care unit contain moisturizer so that caregivers' hands don't easily become cracked and dry.

Factors that employees cite include lack of accessibility to foam dispensers or sinks, simply forgetting to wash their hands, or being so distracted that they just don't stop to do it. Some say the current culture of safety doesn't stress hand hygiene at all levels, and doesn't hold employees accountable.

"Some employees say that their hands get cracked and dry when they wash them," Breazeale said. "If that's happening, then we want to make lotion available."

Others thought they didn't need to wash because they were wearing gloves, or didn't wash because it was too much trouble to take off their gloves. Some say they haven't been properly educated.

"Leadership wants to effect change by identifying and breaking down the barriers employees say get in the way of hand washing. Only then can the culture of accountability in preventing infections gain a foothold. By partnering with front-line caregivers for solutions, we can create a system that leads us to do the right thing for patients," said UMMC chief quality and patient safety officer Dr. Phyllis Bishop.

UMMC cardiovascular intensive care nurse Taylor Vick takes time to wash her hands before entering a patient's room.

The Just in Time coaches give immediate feedback to employees, and promote a culture that's not punitive when it comes to asking a coworker if he or she has washed their hands. "People don't speak up because they're afraid of how their supervisor will react, or they're afraid of hurting a coworker's feelings. We can, and must, get beyond this phase for the benefit of patients," Henderson said.

Cardiovascular ICU nurse Margaret Sykes says hand-washing expectations have been made very clear to her. "When you first come to work that morning, before you go into a patient's room, you wash your hands with soap and water," said Sykes, a registered nurse in her 13th year at UMMC. "You always do foam when you go in a room and out of a room. We call that foam in and foam out. You always wash your hands before and after a procedure."

If caregivers in her area don't follow hand hygiene, she said, it's likely in an emergency situation where a nurse preparing to enter a room sees a patient is unstable.

No one is 100 percent perfect - and that includes physicians and residents who sometimes bristle when told they didn't take precautions, Sykes said. "We've tried to encourage newer staff not to be afraid to say something," she said. "You need to remind them, because you are the patient's advocate. We have to make sure that we are taking care of them in every aspect."

- The Medical Center will use the hand hygiene "targeted solutions tool" of the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare to measure performance, analyze the data, and track improvement. The hand hygiene team will continue observations and show data that includes employees' top barriers to hand hygiene.

The Medical Center also is increasing the use of educational materials throughout the hospitals to drive home the message that preventing infection rests in the hands of all caregivers.

Having a strong hand-washing program that is employee driven is good not just for patients, but for the entire Medical Center community, UMMC leadership says. And with flu season just beginning, it's important to protect not just patients, but the employees who take care of them.

"We hope over the next six months to drive hand hygiene compliance up to 80 percent," Henderson said. "We want everyone to take part. It's about reducing harm, and improving outcomes for our patients. If we do this well, it will show we can achieve significant improvement in many areas."