Medical Center does deep dive into data

We live in a time when advertisements follow people across the Internet and personalized grocery store coupons arrive in their mailboxes.

It’s the era of Big Data.

Groups ranging from start-up businesses to international organizations are harnessing insight from the information people volunteer.

But while companies primarily use data to sell products, the University of Mississippi Medical Center and similar institutions are using it to improve health care.

The definitions of big data are as wide-ranging as the information collected itself. Dr. Richard Summers, UMMC associate vice chancellor for research, said it is “the capture of information on a broad, undifferentiated scale.”

“From big data, we are able to find associations that we didn’t know existed previously, and we can use that information to drive research questions and look for better ways to treat our patients,” Summers said.

At UMMC, these data include measurements, diagnoses, financial transactions and other records from encounters between patients and Medical Center clinicians.

Each piece of information becomes a fish in the big data sea: Since January 2013, that sea includes information from 750,000 unique patients and more than 24 million patient encounters. Most of UMMC’s data comes from Epic, the institution’s electronic health record.

The Center for Analytics and Informatics, or CIA, is the steward of this “sea.” The center develops tools for managing the complex collection and applies analytics to aid UMMC’s mission areas.

“The goal of analytics is to answer why things happened and to determine if we can predict what happens next,” said Alexandra Castillo, executive director of the CIA.

For example, by looking at records of previous heart attack patients, the CIA and clinicians can determine which incoming patients are more likely to have complications during their hospital stays and can prepare to manage those patients more intensively.

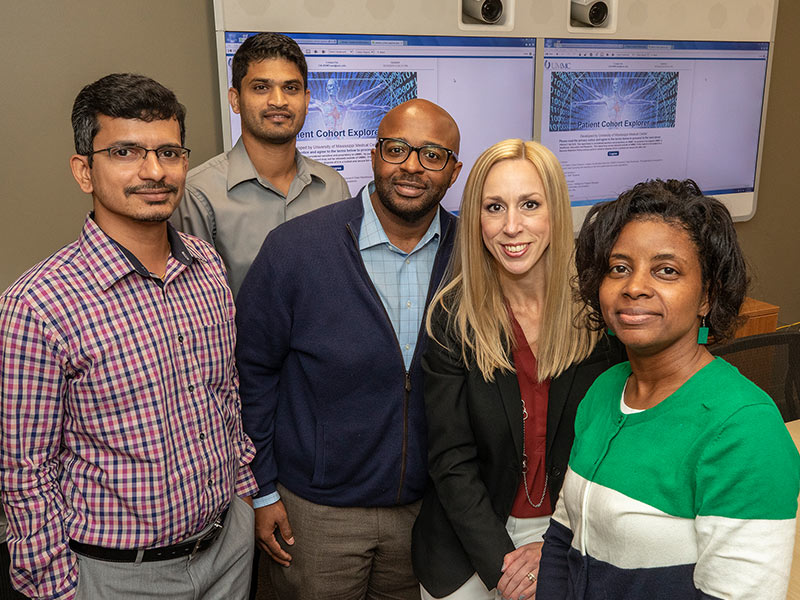

Data from health records also fuel research tools like the patient cohort explorer, a resource that contains de-identified patient information that the CIA introduced in December 2017.

For example, Summers said he’s recently used the patient cohort explorer for exploratory research on risk factors associated with low birthweight and to gather information on emergency department admissions for gun-related injuries.

“Researchers can use it as a preparatory tool before applying for grants, and some complete retrospective studies can be done,” said Fremel Backus, intelligence program manager for research in the CIA.

Backus leads orientation sessions on how to use the cohort explorer for their own projects. This fall, he had held trainings for teams including the emergency department, psychiatry, endocrinology and nursing.

“There’s a huge difference between Epic and the patient cohort explorer,” Backus said. First, the users aren’t accessing Epic, which is information tied directly to a specific person. Rather, they’re accessing the data in a separate environment known as the research data warehouse.

“The data warehouse serves as one source for all of the data collected across the institution,” said Ramona Sandlin, manager of enterprise informatics for the CIA. This practice, referred to as “single source of truth,” helps preserve the integrity of the data, Sandlin said.

In essence, the practice stems from the principle that the more people or offices information must pass through to reach the end user, the more opportunities there are for errors or misuse.

This leads to an important point. Patients aren’t just data; they are real people. UMMC has procedures to safeguard protected health information, or PHI, whenever data are used.

First, the CIA de-identifies the Epic data it makes available through the research data warehouse. The center removes PHI like names, birthdates and medical record numbers. This initial process takes several months, Castillo said.

UMMC’s data resources also support health care across the state. For example, Castillo said the Medical Center has a real-time data sharing agreement with the Mississippi Division of Medicaid – a first of its kind program – and an agreement with the Mississippi State Department of Health.

Furthermore, UMMC is a member of the Mississippi Health Information Network, an electronic exchange of patient information that allows providers quick, secure and reliable access to UMMC patient health records from other clinics and hospitals. It can provide a UMMC patient’s complete medical history at the point of care, so clinicians can know about conditions or past procedures that may affect the care plan.

“This also allows UMMC patients seen in other clinics to be followed longitudinally,” Castillo said. “We have never had that capability before.”

As of 2018, 60 Mississippi hospitals are active participants or preparing to join the MSHIN, representing about 73 percent of Mississippi residents.

Training people who can analyze and visualize data is critical to the future of the Medical Center and Mississippi. In their second year of operations, the M.S. and Ph.D. programs in biostatistics and data science in the John D. Bower School of Population Health now have 11 students.

And this expertise is greatly needed now as UMMC’s data warehouse has become more sophisticated and massive, Summers said.

“Before electronic health records, if one wanted to analyze their practice or patients, it required pulling physical charts,” he said. “Now we are reaching the brink where data collections are of such a large size that it’s becoming more difficult to make sense of it without implementing machine learning.”

“Machine learning is a new version of these same ideas, but training computers to complete the tasks,” Wilkins said. “People are better in some places, but when we are talking about hundreds of thousands of data points, these data sets become very large and it becomes more useful to rely on computers.”

Wilkins and Summers are two of the leaders in UM’s Big Data flagship constellation. The team’s goal is to pursue solutions on how to gather and secure data, developing more powerful applications to analyze and visualize data in order to serve a variety of fields, including medicine and health. Wilkins said the group recently accepted applications for seed grant, and is creating a seminar series that will feature big data-related talks at the Oxford and Jackson campuses.

The first topic Wilkins wants the series to address? The ethics of big data.

“People volunteer their personal data believing that [the users] will do well by them and because they want to help others,” Wilkins said. “There’s a lot of good that can be done, but they deserve to know that they are dealing with reputable, responsible organizations.”