Ketogenic diet can bring success when epilepsy medications fail

Published in News Stories on September 10, 2015

William Bradley Harris was a witty, happy, normal 4-year-old boy until April 2013, when he collapsed after a T-ball game.

"I work in the medical field, so I was going through all the things it might be in my head. Maybe he's dehydrated. Maybe it's low blood sugar," said his mom, Laura Harris of Ocean Springs. "He was very confused… didn't know who I was. He acted very strange for about five to 10 minutes.

"I thought maybe I'm just overthinking it. That night he was fine."

Laura Harris has her witty, fun 4-year-old back, thanks to the success of the ketogenic diet.

Bradley was seen by a cardiologist, an endocrinologist and a primary care physician. They decided to treat the episode as resulting from low blood sugar.

"Then one morning we were stopped at a stop sign on the way to preschool, and he made this really strange sound," said Harris. "I looked into the back seat. His head was leaned back, and his eyes were rolled back in his head.

"I asked him if he was okay, and he said 'yes' as if he were really mad."

When Bradley and his mom arrived at preschool, he was confused and did not know where he was for about five minutes. Harris was reluctant to leave him, but being a young mom just starting out in her career, she was afraid to miss work.

"I called his primary care doctor and asked that she see him again. She kind of thought, at that point, that I was overthinking it as well."

Days later, Bradley collapsed and hit his head on the tile floor. He was in a full-blown seizure.

"It scared me to death. I'd never been around anyone having a seizure," said Harris.

Bradley was seen by a neurologist, and his seizures worsened. He was having more episodes every day. Eventually, Bradley's preschool informed Harris that he could no longer attend due to the frequency of his seizures.

"I wondered if I was going to have to quit my job to take care of Bradley because no one else could watch him. I was missing days at work. I used up all of my leave time."

Bradley's seizures continued to worsen. He was having 40 to 60 per day.

"He took on a debilitated state. He just drooled. He couldn't walk. He was not the same child."

Lee

That is when neurologist Dr. Mark Lee, a University of Mississippi Medical Center assistant professor of pediatric neurology based in Ocean Springs, told Harris they had two choices: surgery or the ketogenic diet, which took Bradley's parents by surprise.

"This was the third neurologist we had seen, and it was the first anyone had ever mentioned the ketogenic diet to me," said Harris. "Jonathan and I both agreed that surgery was the last option, but the thought of a diet controlling what medication couldn't was the craziest thing."

Dr. Lee put Harris in touch with UMMC's Ellen Wallace, registered dietitian for Dr. Brad Ingram, assistant professor of pediatric neurology at Batson Children's Hospital.

"It's an old treatment. It's not a new thing," said Ingram. "The caveat is that dietary therapy before the 1920s was starvation. There was almost a 100 percent seizure cessation rate, but starving a patient is not a long-term treatment option."

In 1921, doctors at the Mayo Clinic discovered that, by limiting a patient's carbohydrate and protein intake and upping fat intake, the body is forced into ketosis, burning fat for energy instead of carbohydrates, without starvation. Ingram said the diet was prominently used until 1938, when phenytoin was discovered.

"The ketogenic diet disappeared off the map when the first modern anticonvulsant was introduced. It was the age of pharmacy, not dietary therapy," said Ingram. "I think it was a victim of its own simplicity. Dietary therapy was considered crude once there was a medication to prescribe."

That was until 1994 when Hollywood movie producer, Jim Abrahams, while desperately researching ways to control his son Charlie's daily seizures after multiple medications and surgery failed, came across a few pages about the diet in an old book on pediatric epilepsy treatments. The discovery led Abrahams to Johns Hopkins, where the book's author, Dr. John M. Freeman, was willing to try the diet on Charlie.

Months later, a national news story on Charlie's successful transformation, becoming seizure-free on the ketogenic diet, brought the treatment back into the public's eye.

Ingram

Despite being considered antiquated, the ketogenic diet is an exercise in precision. Ingram admits that, although doctors get the credit, it is the dietitian who does all the work. "We are very lucky to have Ellen. She is a crackerjack dynamo with the diet, and the families love her to pieces."

"Funny thing is, I have patients who come to see me because they found Ellen on Google."

Wallace manages about 25 patients following the ketogenic diet. "I prescribe every gram of food these kids get to eat," said Wallace. "Historically, dietitians just prescribed a stick of butter. I feel like I'm a nicer dietitian than that.

"We try to get creative. Their milk at meals might be watered-down heavy cream with sugar-free, vanilla coffee flavoring syrup or some strawberry sugar-free drink mix. We have to work the grams of carbs in the flavoring into the meal plan."

Wallace said that it is not known exactly why or how the diet works. When the ketogenic diet causes the metabolism to switch to burning fat instead of sugar, ketone bodies cross the blood-brain barrier and act in a way similar to some medications.

"The ketones are very brain protective. They are very brain healing. For many patients, two to five years on the diet will provide lifelong benefits," said Wallace.

Because the ketogenic diet requires precise measuring and is hard work to follow, most patients are started on a low glycemic index diet. The low glycemic index diet requires the patient to give up any carbohydrates that cause a rapid rise in blood sugar levels - sodas, chips, cookies and candies - in favor of whole grains, non-starchy vegetables and healthy fats, such as avocadoes.

"The low glycemic diet produces what we call controlled hypoglycemia. We keep carbohydrates at low and steady levels throughout the day, so there are no blood sugar spikes or drops," said Wallace "Sometimes seizures go away with a lower level of the diet, or we'll use that as our building block to get to ketogenic diet."

Bradley started with the low glycemic index diet. "We kept a food log and a seizure log," said Harris. "Before the diet, I counted 83 seizures in one day. After the low glycemic diet, it came down to 60. About two weeks later, we moved to the modified ketogenic."

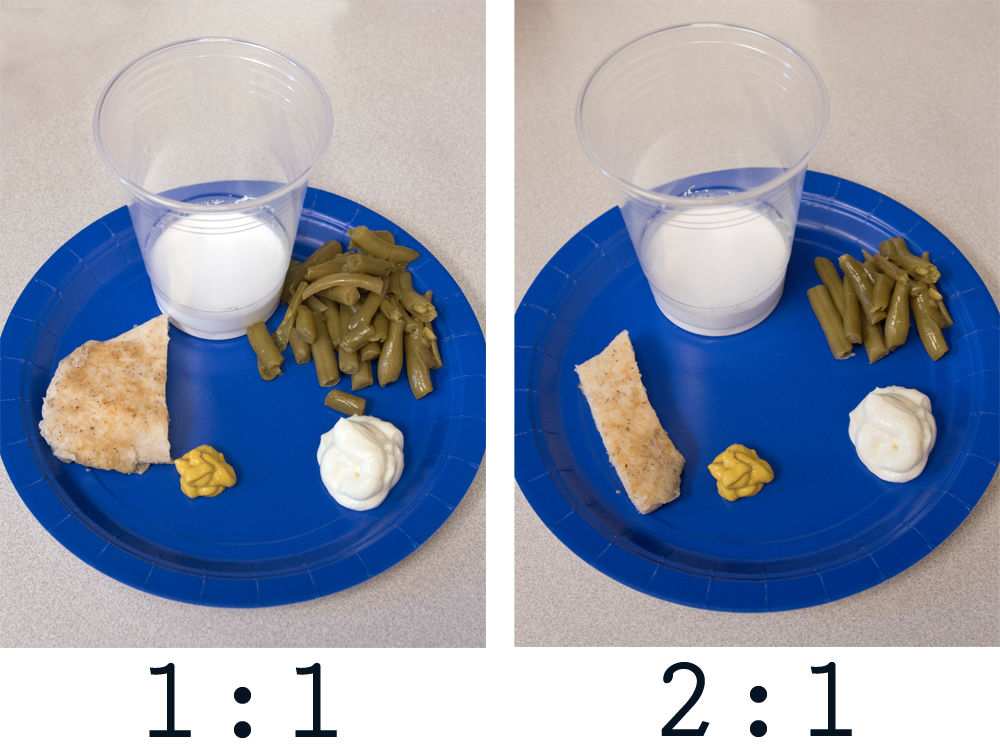

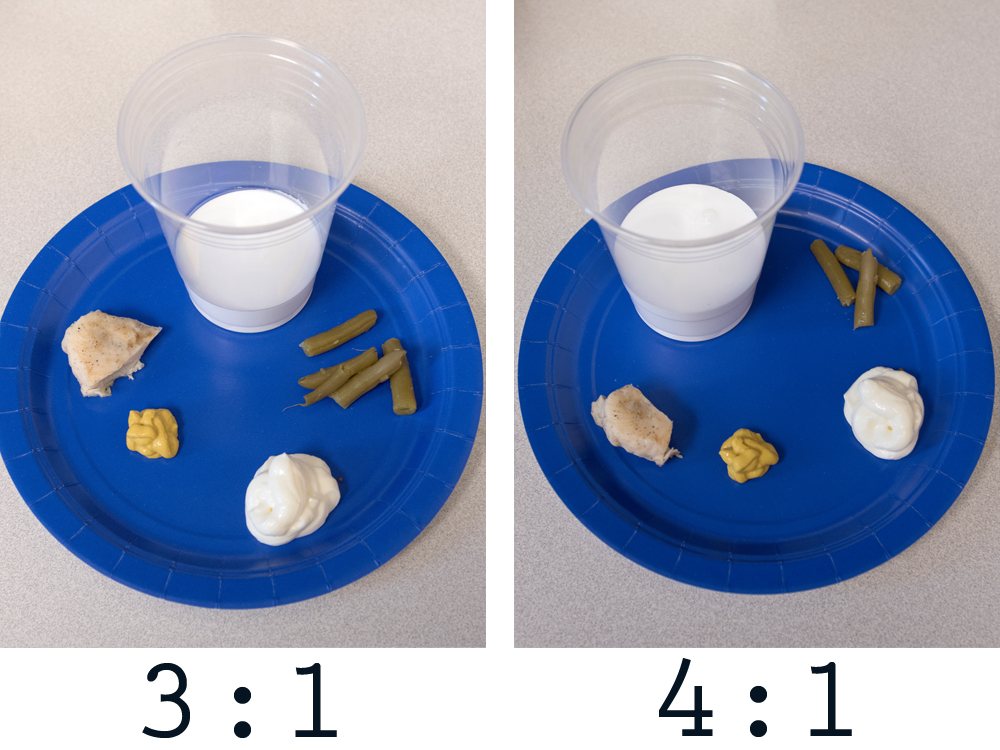

The diet is based on a ratio of fat to carbohydrates plus protein. The ratio ranges from 4:1 or 3:1 for the ketogenic diet and 2:1 or 1:1 for modified ketogenic. There are five grams of carbohydrates in a half a cup of green beans. Twenty grams of fat would be added to the green beans to create the 4:1 ratio, equal to about two tablespoons of butter.

Bradley's favorite hobbies are fishing and baseball, two sports he's now participating in seizure-free.

Bradley was admitted into Batson on Oct. 7, 2013, to transition from the modified to the full ketogenic diet. Parents are trained on the details of the diet during a hospital stay that usually lasts three to four days.

"Of course, it was crazy. I am not going to lie," said Harris. "Here is where I was introduced to the scale. It was stressful and emotional. I was scared. I'm a young parent, so I always question whether I'm doing the right thing.

"As a parent, it's hard to make a child eat something that does not look good. He was dipping green beans into mayonnaise, pickles in mayo. It was very weird to me and hard to stomach.

"Like I said, his life was totally sucked out of him. Before the seizures, Bradley was so witty. He was the funniest little 4-year-old. Watching him go through the seizures - seeing him transformed into something so horrible - I didn't mind doing all that for him."

On the third day of the diet, Bradley only had eight seizures.

"At the hospital was the first time I saw Bradley smile in six months. It was almost like an overnight transformation," said Harris.

Bradley two months after starting the ketogenic diet -- one and a half months without seizures.

The very last day that Bradley had a seizure was June 13, 2014. He has been 100 percent seizure-free for a year and three months. He plays T-ball again, and his mom reports that he is performing excellently in his first grade class.

"I have my baby back. I said this many times to Ellen and Dr. Ingram, but I don't think they realize that they gave me my baby back. There were times along the way when I wanted to quit, but they were always there with encouragement. I can't thank them enough."

Historical Treatments for Epilepsy

Fasting has been recognized as a treatment for epileptic seizures since around 500 B.C.E.

- 1921 - Dr. H. Rawle Geyelin reported on his use of starvation as a treatment for epileptic seizures at the American Medical Association Convention. Drs. Stanley Cobb and W.G. Lennox, both of Harvard, made the connection that starvation caused the body to switch from burning carbohydrates to fatty acids for energy. Dr. Russell Wilder of the Mayo Clinic first proposed the ketogenic diet as an alternative to fasting for seizure control.

- 1938 - Diphenylhydantoin was discovered, and medication became the standard of treatment for epileptic seizures. The ketogenic diet fell out of use as more anti-epileptic drugs were developed.

- 1994 - The Charlie Foundation was started by Hollywood producer Jim Abrahams, whose son Charlie suffered from intractable epileptic seizures and had no success with drug therapies or surgery. NBC TV's Dateline aired Charlie's story, bringing the ketogenic diet from obscurity back into the public eye.

Source:

Wheless, James W., History of the ketogenic diet, 2008.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01821.x/full

For more information about the ketogenic diet, visit The Charlie Foundation for Ketogenic Therapies online.