Chain reaction: Living donors speed up transplant process

If you’re living with kidney failure in Mississippi and need a transplant, chances are you’ll wait an average five years or more for a life-saving organ.

But if you have a living donor, that wait time can be cut to mere weeks or months. And, the donor doesn’t even have to be a match.

That happened for Hugh Smith, a Louisiana resident who received a new kidney Feb. 18 at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, the state’s only transplant center. After decades as a jockey, his kidneys failed, irreparably damaged due to large quantities of ibuprofen he took to fight pain that comes with the sport of horse racing.

A team led by abdominal transplant surgeon Dr. James Wynn placed a kidney donated by a living person from Southern California into Smith’s abdomen, piggy-backing it with his diseased kidneys. That ended daily 10-hour dialysis sessions for Smith, who most recently worked in pest control until his disease forced him into what he hopes is temporary retirement in September 2020.

“They said my kidney started working immediately when they put it in me,” said Smith, 56, who lives in Natchitoches. “The next day, it was functioning at 100 percent. It’s fantastic. It’s amazing. It’s unbelievable.”

And it all began in March 2020 when he met his donor – a 64-year-old mountain biker and ultra-endurance athlete from Plover, Wisconsin – purely by chance at a Natchitoches microbrewery.

If you need one, I’ll give you one

“I’d gotten off work that day, and Mark and his wife were traveling. He does a lot of business with microbreweries, and happened to be there,” Smith said of Mark Scotch, a retiree from the paper mill industry who works part-time marketing hops grown by a Wisconsin cranberry farmer.

The only two people sitting at the Cane River Brewing Company bar, they got to talking, and when Smith later bid Scotch goodbye and thanked him for the visit, “he said he’d buy me another beer if I’d stay,” Smith remembered. “I told him I needed to get hooked up with my girlfriend – the machine I use to do 10 hours of dialysis every night because I’m in stage 5 renal kidney failure. He looked at me like I was a blithering idiot.”

Yes, Smith knows that drinking alcohol isn’t typical for someone on dialysis. His doctor in Louisiana “told me I couldn’t make it any worse,” he said.

Scotch, who took up cross-country skiing, mountain biking, kick-sledding and roller blading in his mid-40s, said he didn’t even think before he said, “’Well, hell, if you need one, I’ll give you one.’ I’d never thought of doing it, but it just came out.”

“I told him then that if I had a nickel for every time someone said they’d give me a kidney, I’d be rich,” Smith remembered.

Scotch was just as serious then as he was the day of his donation.

The logistics were daunting. Scotch doggedly researched kidney donation online, talking to other athlete donors who assured him they returned to their previous level of activity after surgery. Scotch connected with the nonprofit Donor to Donor, learning that he could donate through the National Kidney Registry, NKR for short, and then spoke to staff there.

He found the transplant would look a lot different from how he first envisioned it: Him traveling down South, his kidney going directly into Smith’s abdomen, provided it was a match. And it was not a match.

Need a kidney? Get a voucher

Smith’s new kidney came by virtue of a donor-recipient “chain” facilitated by the NKR. Chains can be long or short, but they create opportunities for literally endless recipient-donor pairings. In short: If someone donates a kidney in your name through the NKR, you receive a voucher to receive a matching kidney from a different donor.

Recipients are transplanted within weeks or months. For Smith, that meant bypassing the median 42-month wait time for Mississippi and nationally. Currently, 899 people are on a waitlist to receive a kidney at UMMC, said Dean Henderson, transplant services administrator.

“I never did look sick. I didn’t have any of the symptoms that came with the disease,” Smith said. Although his kidneys had failed, that alone could have put him years down the transplant list.

Scotch’s research showed that UMMC is one of almost 100 transplant centers that have working relationships with the NKR, and the closest one geographically to Smith. So, Smith transferred his care in late summer 2020 to UMMC’s University Transplant. The game was on.

Scotch donated a kidney in Smith’s name Sept. 30, 2020, at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s University Hospital, which also has a NKR relationship. To encourage other athletes to consider donation, Scotch rode his mountain bike the 100 miles from his home to the hospital about 10 days before the procedure. Surgeons made him rest up at home, then come back for surgery.

Scotch’s organ immediately went to a recipient in New York. That meant Smith received a voucher, going on the NKR list to be matched with a suitable donor, much like Scotch’s recipient was matched with him after someone gave a kidney in that person’s name.

“We had a match in about five days, if not less,” Shelly Watts, a UMMC abdominal transplant coordinator, said of Smith. “But by the time we went through the process, we had to cancel due to Mr. Smith contracting COVID.”

Smith told his primary abdominal transplant coordinator, Brandi Garcie, 10 days before his scheduled Dec. 2 surgery that he’d been exposed. “She sent me to get a test, and of course, don’t you know the damn thing came back positive,” Smith said. “I had to quarantine for 21 days and then have two negative tests about 10 days apart.”

His intended kidney went to someone else. On Jan. 20, Smith was reactivated on the kidney registry. A donor emerged within 48 hours. Surgery was set for Feb. 18. A kidney from a donor in Connecticut would be removed on Feb. 17 and flown to Southern California for transplant that day. That recipient earned their voucher for a kidney because an individual, also in Southern California, stepped forward to make a donation in their name.

That donor’s kidney had Smith’s name on it.

And then a week out from transplant, a historic ice storm paralyzed much of the nation, including Mississippi and Louisiana, stretching from the East Coast to the West Coast. Smith and his parents headed to Jackson on Sunday, Feb. 14.

“If we had waited, we wouldn’t have made it,” Smith said.

“Normally, you just call a recipient in the middle of the night, and that’s it,” Garcie said of contacting her patients when an organ is located. “This was definitely pins and needles .. nerve-wracking.”

University Transplant, NKR make it happen

Watts, Garcie and Henderson worked furiously, arranging transportation and surgery logistics, with Watts the primary liaison between UMMC and NKR. Airports were closing nationwide because their runways were iced over.

Smith settled into his hospital room on Wednesday, Feb. 17. Iced down in a cooler, the kidney was flown via commercial airline to Atlanta at 1 a.m. CST Feb. 18, arriving at 10 a.m. CST. Procedure calls for it to go by charter plane from Atlanta to UMMC, but Jackson’s airport was closed. Instead, the charter plane left Atlanta at 10:15 a.m. CST, landing in Hattiesburg at 11:33 a.m.

A waiting ambulance drove the kidney to UMMC at 11:38 a.m. “No matter how good a driver you are, ice is ice,” Henderson said of the trip up Highway 49.

The ambulance pulled into a UMMC Emergency Department bay at 1:25 p.m. From there, an ED staffer walked the ambulance crew member to the OR control desk, and the organ was hand-delivered at 1:41 p.m.

“I’ve never watched a clock so hard in my life,” Smith said. “The doctors and nurses told me they had 25 people working on it, and that they were going to make it happen. And at about 2:15, they came down and got me and took me to surgery.”

The kidney made it to the OR at 2:02 p.m. Surgery began after Smith was rolled in at 2:27 p.m., about four and a half hours later than planned, “but it didn’t affect the kidney’s function at all,” Wynn said.

“As I reflect on it, I’m still amazed at the teamwork and the people who stepped up to help us out,” Watts said.

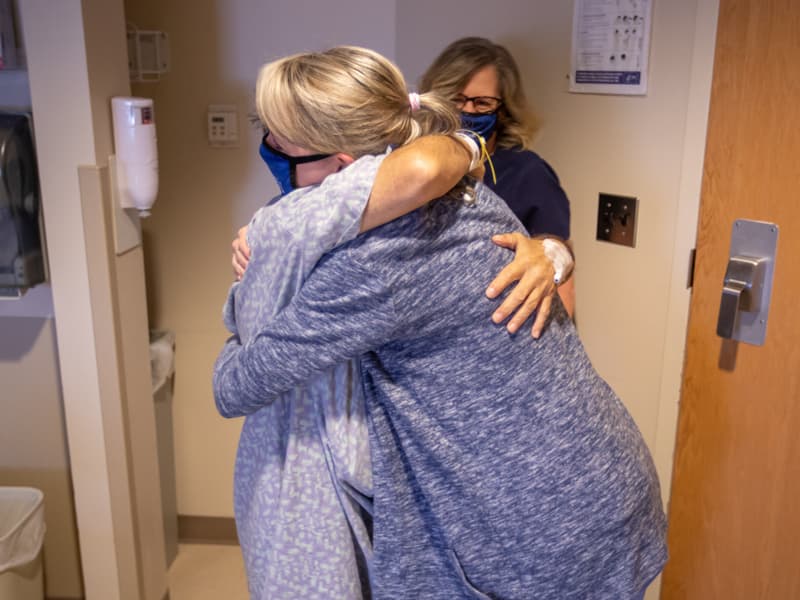

Smith woke up from surgery feeling the change in his body, and having less pain than he’d anticipated. First thing, he called Scotch. He was back home in four days.

Smith’s kidney chain surgery is the first of many to come, said Wynn, a long-distance gravel bike rider who can knock out 100 miles in a weekend. “In Mr. Smith’s case, there were three transplants done in the chain. Without the chain, none of those transplants would have happened. This can magnify the gift of an organ tremendously.”

In the works, Wynn said, is a kidney chain for a UMMC pediatric patient who has a donor who isn’t a match, but who will donate so that the child can get a transplant through the NKR. That surgery, Watts said, will be a “paired exchange” in which a chain of two donors and two recipients are lined up in advance.

“We will have four people going into surgery, all within a 24-hour period,” she said.

Kidney chain gang

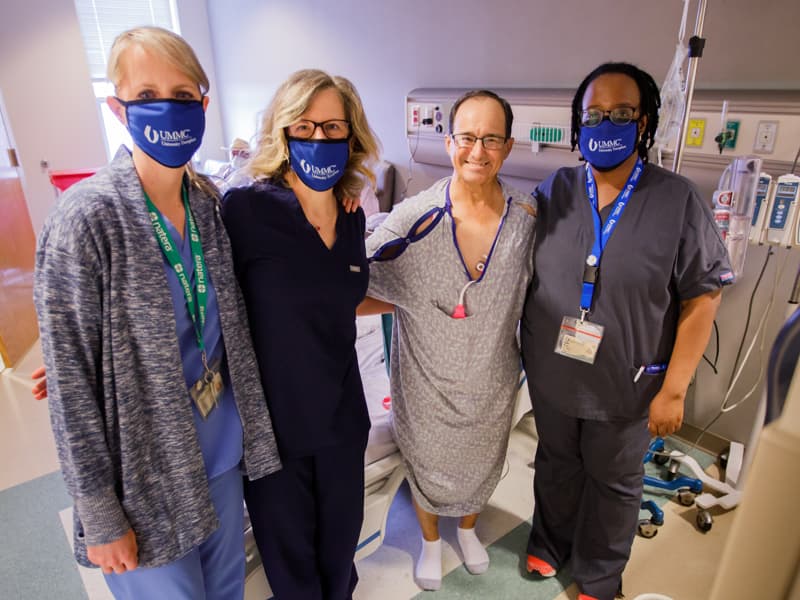

Smith loves his transplant coordinators and surgeons. “Dr. (Felicitas) Koller is sweet as she can be,” he said of Koller, an assistant professor of transplant surgery who took part in the procedure. “The doctors, the nurses, the whole entire staff – they are excellent at what they do.”

On April 24, Scotch and anyone who wants to go with him will begin riding their mountain bikes from Madison, Wisconsin, to Natchitoches, following the Mississippi River in a 1,500-mile, four-week endeavor he’s calling The Organ Trail. He and wife Lynn are avid travelers, covering thousands of miles in their motor home as they explore the country and get in some mountain biking wherever they land.

Next, he’ll ride his bike to Southern California. After that, his organ trail will take him to New York. Follow his journeys here.

“People think it’s kind of strange, but it depends on the person,” he said of his decision to donate. “That’s why we’re doing the awareness rides. We assumed that everyone who needs a kidney gets one, but 13 people die a day for lack of a transplant. My wife decided to donate, too. Her surgery is a month from now. Why wouldn’t she do this?”

His wife’s kidney chain? “That’s another ride,” he said.

“Mark and I are like brothers,” Smith said. “He started this whole process, and he will forever be part of our family.”