Improved family time among CAY interaction therapy goals

Published in News Stories on March 09, 2017

Mia Nasif immersed herself in play, naming each of the residents of a two-story doll house.

“There's mommy, and daddy, and grandma,” she said before the doll family began a pretend adventure involving a raccoon and a bear.

“Mia, share the little girl (doll) with me,” her mother Sarah said. Mia hesitated for a few seconds, but then complied.

It may sound like imaginative play between a child and parent, because it is, but for the Nasif family and others, it is so much more.

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy, or PCIT, offered at the Center for the Advancement of Youth at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, is that instruction book that parents may wish their children came with, said psychologist Dr. Dustin Sarver, assistant professor of pediatrics.

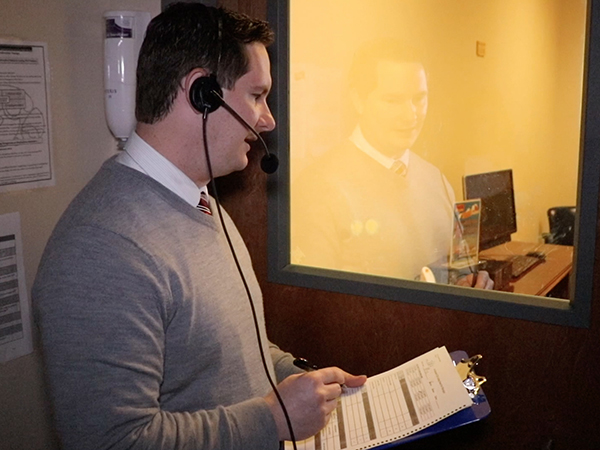

The therapy puts the child in a play situation with a parent, who is wearing an earpiece to hear coaching from psychologists in the next room. The doctors watch, by way of a two-way glass, and listen to the interaction between parent and child, coaching the parent through the situation as it unfolds.

The evidence-based treatment for young children with emotional and behavioral disorders places emphasis on improving the quality of the parent-child relationship and changing interaction patterns between parents and their children.

“It minimizes the amount of time parents get upset in the moment and gives parents specific skills to enhance their parenting,” Sarver said.

Sarver coaches parents in a separate room, giving them feedback through an earpiece on their interactions with their children.

PCIT is funded by a grant from the Mississippi Council on Developmental Disabilities, which awarded $50,000 for the first year of therapy service. The project is now in its second year of funding, with MCDD awarding a $54,000 grant.

“The Mississippi Council on Developmental Disabilities seeks to improve the quality of life for people with developmental disabilities. Bringing evidence-based practices such as PCIT to treat emotional and behavior challenges can improve quality of life for parents, caregivers, and children with developmental disabilities,” said Charles Hughes, MCDD executive director. “Preparing professionals to offer these services is critical for families who need access to additional health provider options across the state.”

Mia's parents, Sarah and Chris, learned that their daughter has a neurological disorder that can be challenging to her physically, leading to behavior issues.

“It can give her a lot of frustration,” Sarah Nasif said, “and she can be a very strong-willed child.”

Sarah Nasif asks daughter Mia to share a doll during a therapy session.

The Nasifs, of Madison, learned about CAY and PCIT from neighbors and started therapy in October 2016. “It's been a wonderful experience,” she said. “I was feeling out of control before October. Mia was running the house.”

“It takes time,” Chris Nasif said of the therapy, “By the end of December and early January, though, we could see a huge difference.”

During each weekly session, psychologists and parents track children's behavior and positive parenting and discipline skills during therapy, Sarver said, “so progress can be measured individually from the start through the end of treatment.”

Playtime interactions are used throughout treatment at CAY to coach parents in situations ranging from easy to challenging. Therapy begins by teaching positive interaction skills that build the relationship, but then progresses to learning how to use effective discipline techniques. Good behavior is practiced in the clinic before outings because, “if you can't obey your parents in the playroom, then you won't at McDonald's either,” said Sarver.

Parents learn how to handle challenging interactions in the safety of the clinic but then learn to do the therapy skills at restaurants, shopping malls or other public venues before the patient “graduates” out of care.

PCIT includes Child-Directed Interaction, during which parents encourage and attend to their children's positive social behaviors and learn to strategically ignore minor negative behaviors, and Parent-Directed Interaction, a time where positively stated commands are given in a normal tone of voice with effective follow-through. When commands aren't followed, a thorough time-out procedure follows.

“So much of PCIT is about training the parents as well as the child,” Sarver said. “PCIT is fueled by good, positive reinforcement to good behavior and a solid attachment between children and their caregivers.”

Keeping parents from having their own meltdowns when dealing with their children's emotional or behavioral disorder means more positive interactions between children and parents, he said.

“In general, parents can be overly harsh when dealing with children with behavioral disorders,” said Sarver. “It is easy to forget to balance out punishment with warmth.”

Sarver and his wife, psychologist Dr. Nina Wong Sarver, also an assistant professor of pediatrics at UMMC, along with psychologist Dr. Dorothy Scattone, associate professor of pediatrics, and licensed clinical social worker Genevieve Garrett, offer the therapy to children with behavioral difficulties after referrals to CAY.

The Nasifs were quick to note that PCIT only works when parents are committed to participating and learning.

“I wish every family could be as committed to participating and experience the successes the Nasifs have had,” Sarver said, praising Chris and Sarah.

As for Mia, who is nearly 5 and is soon to graduate from therapy, she's getting ready for school, where her increased cognitive, language and social skills gained through PCIT will help her adjust well to kindergarten.

Family time for the Nasifs, since therapy, is more a source of joy than stress, something all parents want. Said Sarah Nasif: “We now have peace in our home.”