NICU’s team of specialists care for rising numbers of low birthweight babies

Editor’s Note: Over the next three weeks, we will take a closer look at the University of Mississippi Medical Center’s work through its three-part mission of education, research and health care to address the state’s maternal health crisis. These stories, which will be part of an occasional series examining the state’s only academic medical center’s role in fighting some of the most pressing health issues, share the experiences of caregivers, researchers, patients and learners. We hear from those affected by maternal health challenges and from those who are fighting against them in the hospital room, lab and classroom.

Mothers’ health and the health of their babies are intertwined. When mothers lack access to the care they need, that vital connection weakens, increasing the risk of health issues for their babies.

Mothers’ health and the health of their babies are intertwined. When mothers lack access to the care they need, that vital connection weakens, increasing the risk of health issues for their babies.

“There is so much overlap between the health of mothers and babies,” said Dr. Ira Holla, assistant professor of neonatology and quality director in the University of Mississippi Medical Center Division of Newborn Medicine. “When mothers cannot access the care they need, their babies may need advanced neonatal care.”

Babies born at 35 weeks’ gestation or less and those born with complications usually require neonatal intensive care. Children’s of Mississippi, UMMC’s pediatric arm, includes the state’s only Level IV neonatal intensive care unit, the highest level of care

Nationally, the number of babies born at less than 5 ½ pounds, considered low birthweight, is more than 315,000, some 8.6% of newborns, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The number of babies born pre-term, which can make low birthweight likely, was 380,548 in 2023, more than 10% of babies born.

In Mississippi, the pre-term birth rate for 2023 was 15%, an increase from 14.8% in 2022 and 13.1% in 2013. Among African American mothers in the state, the rate was 18.2%. This not only surpasses the rate in other racial and ethnic groups in Mississippi but is also significantly higher than the national rate of preterm births for African American mothers, which stands at 14.7% according to the March of DImes.

Less prenatal care, higher risks

When mothers don’t get the prenatal care they need, they and their babies are at risk for undiagnosed conditions that can be life-threatening.

Hypertension, dubbed a “silent killer” for its lack of noticeable symptoms, “is extremely high in the birth cohort in our NICU when compared with other women with babies in the Vermont Oxford Network,” said Dr. Mobolaji Famuyide, chief of pediatric neonatology.

The VON is a nonprofit voluntary collaboration of health care professionals working together to improve neonatal care.

For 2024 in the VON, among babies born at 1.1 pounds to 3.3 pounds, about 39% were born to mothers with hypertension, or high blood pressure. In UMMC’s NICU, that percentage was 54%.

“When plotted on a bell curve, that puts the cohort in our NICU above the 75th percentile,” she said.

Preeclampsia, a serious pregnancy complication that typically develops after the 20th week, is characterized by high blood pressure and signs of organ dysfunction, often affecting the kidneys or liver. One of its key indicators is the presence of protein in the urine. If left untreated, preeclampsia can pose significant risks to both the mother and baby, potentially leading to severe or life-threatening complications.

“Sometimes, when preeclampsia becomes severe, the only way to protect the mother or baby is to deliver the baby right away, even if it’s too early,” Famuyide said. “This can lead to premature birth, which brings its own set of complications for the baby’s health.”

For babies, uncontrolled hypertension in the mom can lead to less blood flow to the placenta, which can slow growth or cause low birth weight. Sometimes an early delivery is needed to prevent life-threatening complications from high blood pressure for mothers and their baby.

Magnesium sulfate is given to mothers with preeclampsia to prevent seizures, but that can result in grogginess in babies. “Those babies may need respiratory support till the magnesium wears out of their system and will need to be admitted to the NICU for ongoing monitoring and support,” Famuyide said.

Later on, babies born to mothers with high blood pressure have a greater chance of developing diabetes and hypertension later in life, Holla said.

“Not only can hypertension have immediate effects during pregnancy, but it also has long-reaching consequences later in a baby’s life,” she said.

Certain chronic health conditions, including Type 2 diabetes and hypertension, have been associated with an increased likelihood of preterm birth. Studies also indicate that weight-related health factors can contribute to this risk, particularly when they lead to conditions such as high blood pressure.

Babies born to diabetic mothers can develop hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar, after birth. Diabetes in the mother can result in too much insulin in their systems, which will cause low blood sugar, and can delay production of surfactant, which is needed for lung maturation.

Also among the risks of inadequate prenatal care is undiagnosed and untreated syphilis in the mother, which will result in congenital syphilis, Holla said, noting that Mississippi has a congenital syphilis rate that’s among the nation’s highest.

Syphilis, which is easily cured with penicillin, can be passed to unborn children through the placenta or during birth. Most babies with congenital syphilis don’t have symptoms at first, but later, blindness, deafness, seizures, neurodevelopmental delays, teeth and skeletal deformities and the collapse of the bridge of the nose, may appear. The disease, if untreated, can be fatal.

Life-saving NICU care

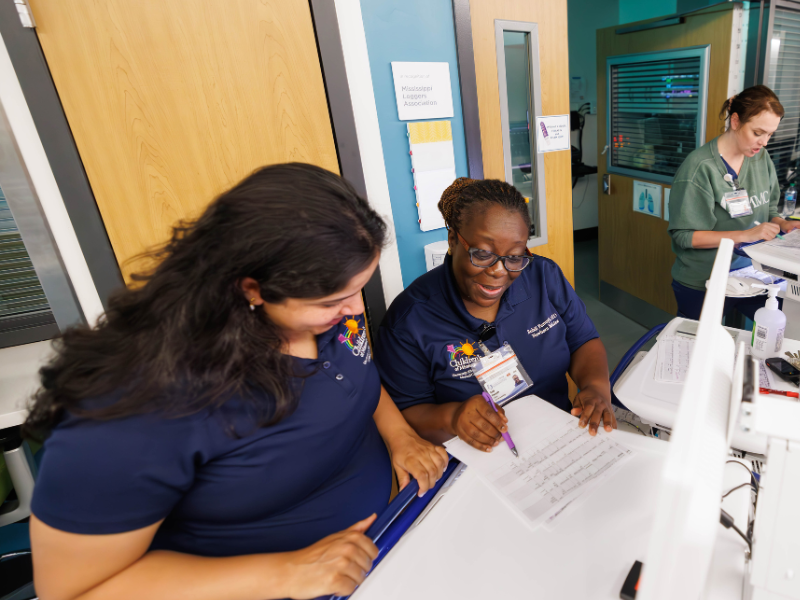

Newborns in UMMC’s NICU receive around-the-clock care from a team of experts that includes neonatologists, neonatal nurses, respiratory therapists, and pediatric specialists such as cardiologists, pulmonologists, neurologists and surgeons.

Parents of babies in NICU care will often see wires for monitoring breathing, heart rate, blood pressure and temperature and tubes to bring fluids, medicines and extra oxygen. Some babies may also need to be on a respirator.

“Even at 30 to 32 weeks’ gestation, babies may still need help with breathing,” Holla said.

Babies born prematurely or at low birthweight are at increased risk for brain bleeds. This can be lessened with two prenatal doses of steroids, with the last delivered at least 24 hours before birth.

“If a mother comes into the Emergency Department ready to give birth, she won’t be able to get two doses,” she said. “Some moms don’t get any doses.”

Premature newborns need help with nourishment, too. Babies younger than 34 weeks’ gestation may need a nasogastric tube to take in enough nutrition, and breastmilk is recommended for newborns in intensive care.

“Mother’s milk is best,” Holla said, “but mothers with their own health challenges may not be able to pump the breastmilk their babies need. We then turn to the Mothers’ Milk Bank of Mississippi for donor milk as a bridge until mothers recover.”

Breastmilk lessens the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis, a life-threatening and fast-spreading bacterial infection of the gut.

Premature infants are also at a higher risk for neonatal sepsis, a blood infection. “The risk is much higher for preterm babies,” Holla said. Mothers in preterm labor begin antibiotics to decrease the risk.

Continued care post-NICU

Children’s of Mississippi offers a newborn follow-up clinic for children who started their lives in neonatal intensive care and nursery. After the first clinic visit, infants are referred to their primary care provider, but chronically ill babies, very-low-birthweight babies and those at risk for developmental disabilities are seen for developmental evaluation at 4 months, 9 months, 15 months, 18 months and 24 months by a team that includes a neonatologist, general pediatrician, developmental pediatrician, neuropsychologist and therapists specializing in occupational therapy, physical therapy and early intervention. Many of these highly specialized professionals can only be found at UMMC. Babies may also be seen by pediatric subspecialists including ophthalmologists, audiologists, neurologists, pulmonologists, cardiologists, surgeons and geneticists as needed.

However, the obstacles for mothers getting the prenatal care they needed during pregnancy can be the same challenges to reaching care for their babies.

“This affects how we practice in the NICU,” Holla said. “We want to make sure they get the care they need while they are in the hospital.”

NICU babies who need advanced neonatal care often face the same access challenges as their mothers, she said, particularly when it comes to accessing timely and specialized care. As a result, they may have an extended NICU stay to ensure they can safely transition home without the immediate need for advanced follow-up services that may be difficult to access.