A “beRi” good project wins Hackathon prize

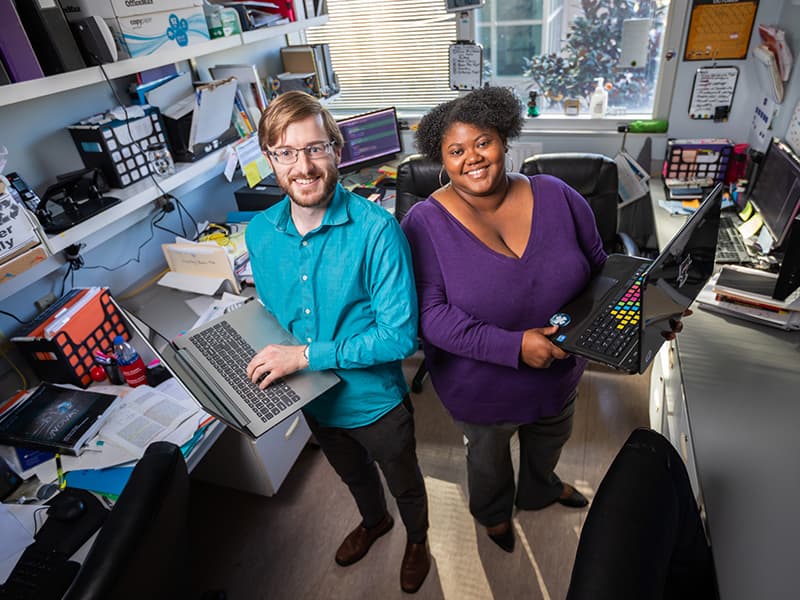

Rob Gilmore and Shaurita Hutchins spend their days at the University of Mississippi Medical Center snaking through complex biological data. Now, they’re captured a prize in an international competition.

They were part of an eight-person team that won the vote for favorite project at HackSeq 2018, a hackathon at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada held from October 12-14.

Their project is called “beri environments for R installations,” or beRi. A package management system for the programming language and statistics program R, they used the computer programming language Python to build a suite of tools for managing and installing R packages.

“beRi is a tool for managing workflow,” Gilmore said. “Its purpose is to increase the reproducibility of results by making it easier for users to run their analyses on different machines.”

Hutchins and Gilmore are researchers in the lab of Dr. Eric Vallender, associate professor of psychiatry and human behavior. The lab primarily works on questions associated with genetics and behavior through bioinformatics, a field that integrates computer programming and biology to analyze complex data.

The inspiration for beRi came in part while analyzing data for a collaborative project with Dr. Courtney Bagge, associate professor and Dr. Craig Stockmeier, professor, both in the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior.

“We were processing RNA sequencing results for a study on gene expression in the brain and impulsivity,” said Hutchins, a West Point native who studied biology at Xavier University of Louisiana and Mississippi College. “We were using the Mississippi Center for Supercomputing Research in Oxford and had some troubles running a script for R, which impeded our analysis.”

Hutchins emphasizes that the issue wasn’t with the MCSR. However, some bioinformatics projects need advanced software configurations. For the impulsivity project, R needed to be set up in a specific way, so Hutchins and Gilmore tried to find a way to configure it themselves.

Gilmore, who grew up in Vicksburg and studied biomedical engineering at Mississippi State University, proposed the idea for beRi as a HackSeq project and applied to be a team leader.

“I’m interested in creating tools that can analyze data and have broad utility,” he said. Because beRi isn’t specific to genomics or bioinformatics, an R user from any discipline for could potentially use it.

“During my interview with the HackSeq coordinators, they said ‘this idea really resonates with us.’ A lot of the organizers were interested in this project, which I thought was a good stamp of approval.”

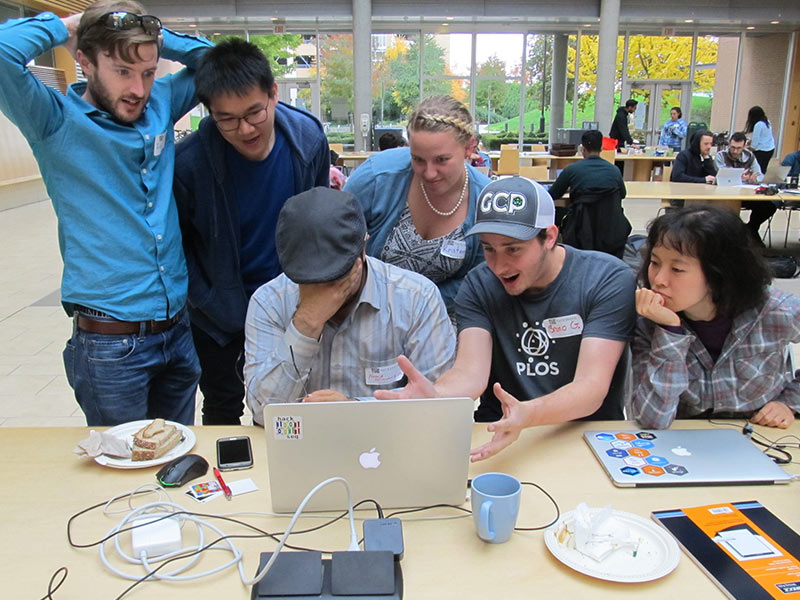

(Photo credit: HackSeq)

Hackathons like HackSeq are events where people develop functional computer software or codes over a short period of time. According to its website, HackSeq is a student-run program which aims to “bring individuals with diverse backgrounds together to collaborate on scientific questions and problems in genomics,” according to their website. The 2018 event had 80 participants working in eight teams.

Team beRi recruited six additional members for HackSeq, including graduate and undergraduate students from UBC and Simon Fraser University, also in British Columbia, and a Microsoft employee from Seattle. For 72 hours, they and seven other teams put together their work in the Life Sciences Institute at UBC, with Gilmore leading on site and Hutchins working remotely from Mississippi.

“We had great synergy,” Hutchins said. “It was as if everybody was really able to read each other’s minds and understood the challenge.”

“Our team had people with the right skill sets that meshed together well,” Gilmore said.

At the end of HackSeq, participants voted team beRi as having the favorite project. The team of eight split a CAD 1500 prize (about $1100) and received “golden floppy disks” as trophies.

“We had people from other teams saying, ‘I want that. I want to use this in my own work,” Gilmore said.

Now, they’re looking for more opportunities to advance beRi. Gilmore and Hutchins just submitted an application for an R Consortium Grant to fund further work. They are also continuing to work with some of their HackSeq team member. Their code for beRi and other bioinformatics tools they are developing is available on GitHub under their alias as the Datasnakes, which they admit is a Python pun.

Gilmore and Hutchins have been working together since April 2015, when they joined the Vallender lab on the same day.

“He encourages his lab members to become independent scientists and problem-solvers,” Gilmore said.

Hutchins agreed, saying that their experience in the lab made her feel capable of taking on new tasks.

“He’s part of the reason we were able to do this,” she said.

“Rob and Shaurita came into my lab with strong biology backgrounds but without much training in bioinformatics,” Vallender said. “When these heavy bioinformatics and computational projects came along I was very pleased to see how much they dove into the work. When they ran into difficulties with implementing the standard bioinformatics pipelines, I thought that they would simply be stuck. Instead they went much further than I ever could have expected. The work and solutions that they have come up with didn't just fix the problems that we were having, they also addressed issues that were pervasive in the field.”