Mass casualty exercise tests emergency, MED-COM readiness

Saturday morning at 7, an ambulance service supervisor made a call to Med-Com, the University of Mississippi Medical Center’s statewide emergency response communications center.

“We’ve responded to a very large accident at the Madison exit,” the supervisor said. “There are a lot of injuries. We don’t know a lot yet, but we’ve got two units en route, along with myself. I’ll give you a call as soon as I know more.”

When an 18-wheeler on I-55 rumbled over the median and struck a charter bus, it started a chain of communication and action, from the ambulance supervisor’s first call to MED-COM to assigning what Jackson-area hospital would care for each of the 50 injured, to giving treatment, be it for trauma or a skinned knee.

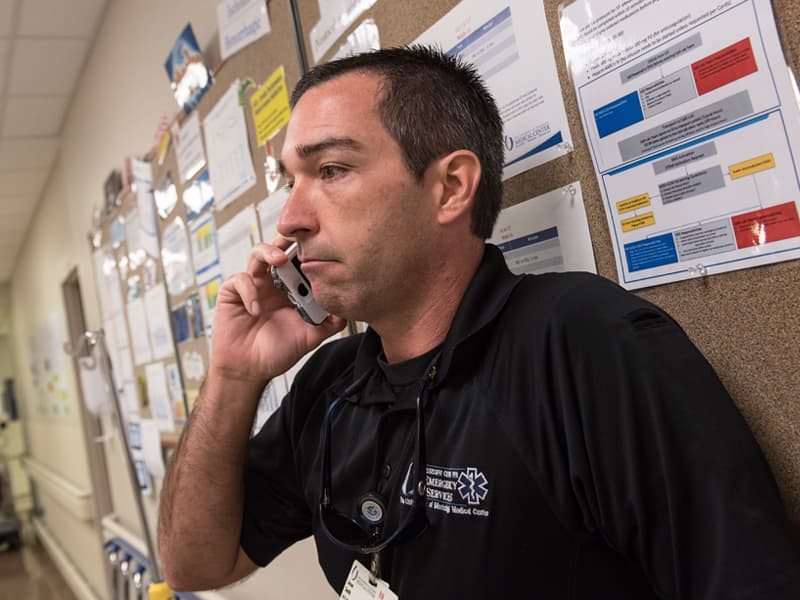

That frightening scenario wasn’t real, and the “supervisor” who made that first call to MED-COM was actually Jason Smith, manager of emergency services at UMMC’s Center for Emergency Services. But the process that should kick in when patients from a mass casualty event arrive at the state’s only Level I trauma center is the real thing – and one that UMMC front-line staff and administrators gave a critical eye Friday during a mass casualty drill.

Operation Wheels on the Bus, the scenario played out by the Center for Emergency Services and other Medical Center administrators and Emergency Department leaders, tested the abilities of a pared-down weekend crew to think on their feet amid crisis and chaos, and to juggle limitations in available staffing, equipment and other resources.

UMMC, at any given time, is staffed with trauma surgeons and nurses to handle injuries and mass casualties, be it a barroom shooting that send a half-dozen patrons to the ER, or something much more unthinkable.

Several years ago, the Medical Center added four trauma bays that can double, if needed, as operating rooms. The adult Emergency Department has 51 beds, including trauma, Rapid Track, observation and psychiatric. The pediatric Emergency Department has 23 beds.

The Medical Center has 15 standard operating rooms and nine pediatric ORs, and the School of Medicine’s simulation operating room is equipped for actual surgery in an emergency.

The Conerly Critical Care Tower’s four floors can accommodate a total 80 patients; the neonatal intensive care unit, 102 patients. Generally, the ICU floors stay near capacity, as does the NICU. That means that in the event of a mass casualty, some ICU patients would be reassessed to determine if they could be moved to make room for others.

Friday’s four-hour exercise began at 8 a.m. and followed 25 patients – on paper, not in the flesh – as they flowed into the adult and pediatric emergency departments. A group of about a dozen emergency medicine leaders picked up the drill once Smith made his initial phone call to MED-COM’s team of communication specialist dispatchers.

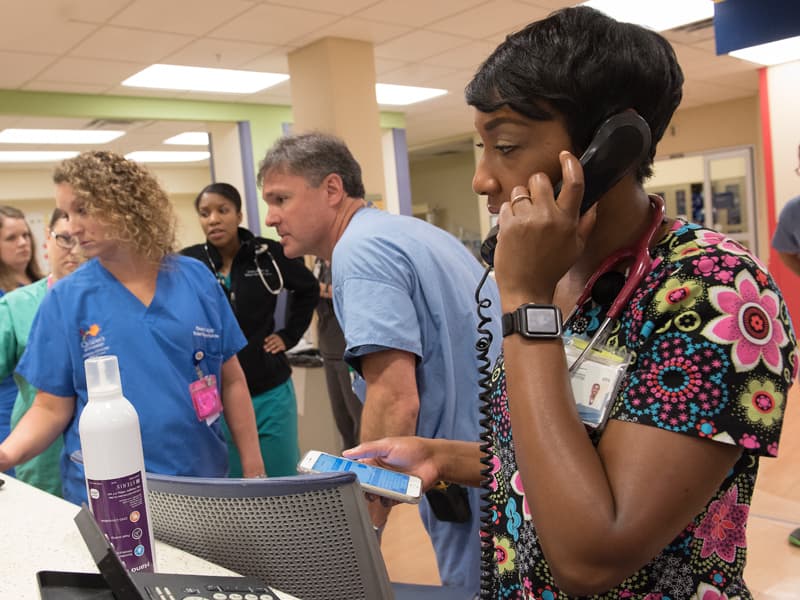

MED-COM issued the Medical Center’s Code Green, which means UMMC has activated its emergency operations plan, via overhead speakers throughout the hospital areas.

Almost immediately, dispatchers led by supervisor Jean Dobbs began calling area hospitals, explaining that an exercise was being conducted, and that MED-COM needed an immediate count on the available beds at each facility. That helps the Medical Center manage patients toward the level of care needed, leaving beds at UMMC for those most critically injured.

“It’s just a drill. It’s just a drill,” Candice Talley, a MED-COM communications specialist and paramedic, told a nurse from the adult hospital who called to ask what a Code Green is.

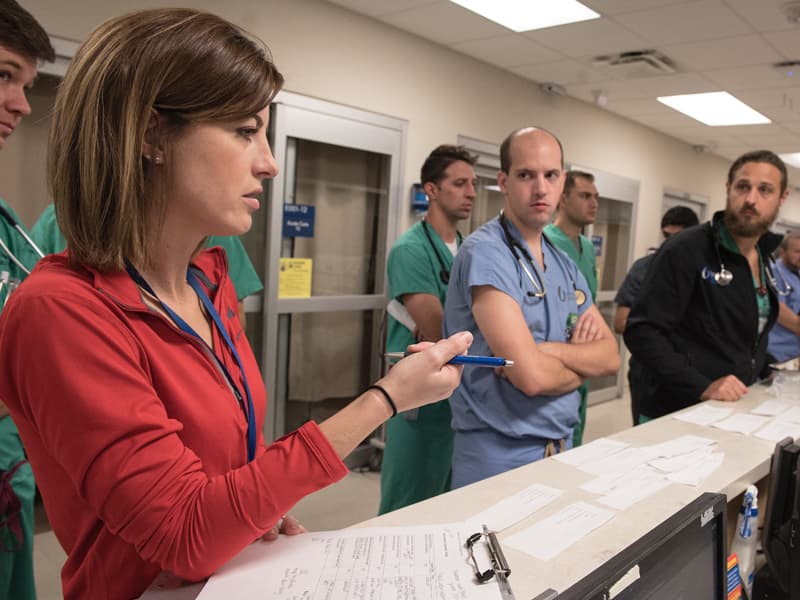

In the adult and pediatric emergency departments, clinical leaders huddled with staff and asked the same questions: Where will you put incoming patients? What’s your staffing? What resources do you lack? How will you get the people, supplies and equipment that you need, and who would make those decisions?

How many operating rooms are available, and are there enough surgeons to staff them all? Who keeps up with what patient is going to which operating room?

As the virtual patients arrived, the leaders including Dr. John McCarter, associate professor of emergency medicine, handed staff slips of paper with a description of what ended up being 25 adult and child patients and their injuries: 47-year-old man, abdominal pain and open left leg fracture. A 40-year-old female, objects stuck in her pelvis, controlled bleeding but weak pulse. A 10-year-old boy with multiple lacerations.

The patients continued to pour in as Rebecca Benson, an Emergency Department nurse manager, ticked off their information. “So, how does this change the game for you?” Jason Zimmerman, director of nursing adult services, asked Brad Harris, an adult ED shift supervisor who on Friday was serving as charge nurse.

On a Saturday morning, Harris said, the ED would typically have 12 nurses on hand. With the influx of patients the bus accident would bring, he said, “we’re pretty tapped out from a nursing perspective.”

Would you call in nurses not on shift? Borrow them from the ICU? From patient floors? How many respiratory therapists are on duty on a weekend morning? How many vents are in the ED, and where can staff get more?

“You have four more patients coming in,” Benson told Harris. He assigns each a trauma room or ED room, based on the injuries listed on the slips of paper. And what happens, Benson said, when you are full and can’t take any more patients?

Dr. James Kolb and Dr. Loretta Jackson-Williams, both professors of emergency medicine, and a group of six emergency medicine residents including Dr. Brandon Myers, enter the mix. “This one, this one, this one … they’re fine,” Kolb said as he assessed the patients on paper. “This one will need to go to the OR. I’d need to call (Dr.) Alan (Jones, professor and chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine) to activate our physicians.”

“That’s an OR,” Jackson-Williams said of the paper patients. “That’s another OR.”

Then, a new wrinkle: “You’ve got four more coming in covered with diesel fuel. What do you do?” Benson asked.

“We don’t want to get diesel fuel all over the staff,” Myers said. “We have to get them cleaned up somewhat.”

“You have nine nurses tied up with patients,” Zimmerman said. “How are we going to get these four new patients decontaminated?”

Smith brought up two key points: Employees not trained in decontamination could take much longer to do the work. And, he said, saving a patient’s life comes first, even if decontamination has to wait.

At about 10 a.m., Smith and leaders from administration and hospital departments gathered to debrief each other on what went well, and what didn’t.

Areas for improvement: No one in the exercise brought up the need to call UMMC’s blood bank, despite 15 patients who needed multiple blood products. The pediatric ED wasn’t included in the initial disaster activation, and it needs a better way to alert physicians in the event of a disaster or mass casualty, said Dr. Benji Dillard, professor and chief of pediatric emergency medicine.

And, a lot of people at the Medical Center have no idea what a Code Green is. “MED-COM got about 30 calls, asking what should we do for a Code Green,” Houck said.

Perhaps one of the biggest positives from the drill was brainstorming on good ideas for the future: Give charge nurses a list of actions they should take until administrators arrive to take care of logistics. Have staff wear color-coded vests – red for physicians, blue for nurses – so that everyone knows each other’s roles and who’s in charge.

“If you’re looking at the Las Vegas shooting, you know that you need to have an incident command system. You have to have a visible way for people to know who each other are,” Smith said.

“We must know our potential,” Zimmerman said. “We have to proactively rearrange the chairs on the deck.”