UMMC expert: Football player’s cardiac arrest spotlights importance of CPR, AEDs, training

The collapse of Buffalo Bills player Damar Hamlin during a Monday Night Football game Jan. 2 may seem rare, but sudden cardiac arrest happens far too often, said Dr. Charles Gaymes, professor of pediatric cardiology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Hamlin’s cardiac arrest “reinforces the need for availability of AEDs and training in their use,” said Gaymes, who is also a cardiologist with the Children’s Heart Center at Children’s of Mississippi and medical director of Mississippi’s chapter of Project ADAM, a program to bring automatic external defibrillators and CPR training to schools.

Cardiac arrest can occur in “otherwise healthy individuals,” he said, “and the underlying cause can be silent.”

Hamlin, who collapsed on national television, received CPR for nine minutes before being taken by ambulance to the University of Cincinnati Medical Center. He was discharged Jan. 11 from Buffalo General Medical Center, where he had been transferred.

That scenario has happened closer to home to athletes who became patients of Gaymes after suffering cardiac arrest.

In 2013, Tyler Free was a 15-year-old playing for the Ocean Springs Greyhounds when he collapsed while running on the football field. He was resuscitated through CPR and an AED and was then flown to USA Health Children’s and Women’s Hospital in Mobile, Alabama, to Children’s of Mississippi in Jackson.

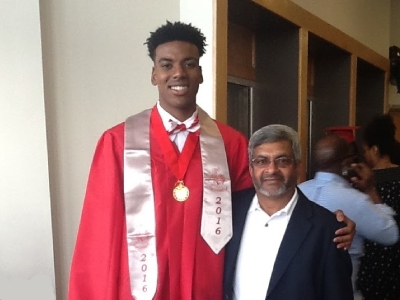

E.J. Galloway felt fatigued during a summer league basketball game at Jackson’s Jim Hill High in 2014 and was called to the bench by Coach Willie Swinney. A few minutes later, Galloway collapsed, and Swinney began performing CPR, saving his life.

Watching Hamlin’s collapse was difficult, Galloway said. “It was like I was watching my experience because they had done CPR on me for about 10 minutes. It was hard to watch.”

Galloway, a 25-year-old Stillman College graduate who hopes to play basketball professionally, said CPR saved his life and Hamlin’s. “Knowing how to perform CPR and being ready is so important.”

Defibrillators are essential, said Free, 25 and a member of the player development team at Hard Rock Hotel and Casino. “I wouldn’t be here without them. CPR and AEDs make all the difference in the world.”

With situations such as these in mind, Gaymes and his team launched Project ADAM in Mississippi. The national Project ADAM organization, started in 1999 after a series of deaths by ventricular fibrillation among high school athletes in Wisconsin and Georgia, seeks to save lives by coordinating CPR and AED training efforts in schools.

“In case someone suffers cardiac arrest, we want the faculty and staff to be prepared and skilled enough to perform CPR and use an AED until emergency responders arrive,” Gaymes said. “It is not complex, and the AEDs are all automatic.”

Any CPR, said Gaymes, is better than no CPR. “The worst thing you can do in that situation is freeze. To save a life, you have to act.”

If someone has collapsed, the first step is to check to see if they are breathing. The next step is to tell someone to call 911 and get an AED to restore the rhythm of the heart.

“It may be eight to 10 minutes before an ambulance can reach you, so you will need to start CPR,” said Jereme King, director of the Life Support Training Center at UMMC. Hands-only CPR involves rhythmic chest compressions of about 100 to 120 a minute, roughly the tempo of the Bee Gees’ hit “Stayin’ Alive.”

“An AED should be used within three minutes,” Gaymes said. “CPR should be started and continued until the AED arrives.”

AEDs offer automated instructions that guide rescuers through the defibrillation process.

“When someone is in cardiac arrest, there is no meaningful electrical stimulation of the heart telling it to beat,” Gaymes said. “We use an AED to restore the electrical rhythm of the heart.”

Underlying conditions that can trigger cardiac arrest can be treated with medication and implanted defibrillators. Symptoms that signal a need for cardiac screening include chest pains, lightheadedness and seizures.

“There is still going to be a percentage of individuals whose condition may not be detected but who are at risk for sudden cardiac arrest,” Gaymes said. “That’s why it’s important to be prepared to resuscitate someone through chest compressions and AEDs.”

Schools interested in learning more should contact the Project ADAM team at the University of Mississippi Medical Center online.

Groups or organizations such as businesses or churches can contact the Basic and Advanced Resuscitation Training Center at UMMC for more information at (601) 984-5591 or by emailing rtc@umc.edu.