A movable feast: Librarian returns artifacts found during lunchtime rambles

For many of his 44 years at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, David Juergens spent his lunch breaks gorging on the past.

When other employees were herding up for a hamburger in the cafeteria or a plate lunch, the librarian retreated to a remote corner of the campus, a solitary figure bearing a sack lunch and a passion for history.

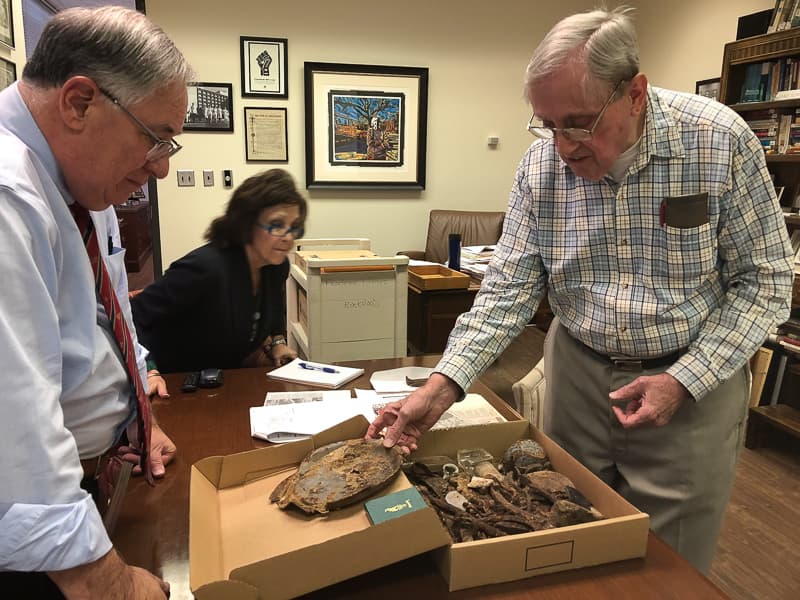

There, he gathered the material fragments of vanished and overlooked lives: medicine bottles; pottery shards; tin plates; nails; the handle of an old, stove-heated “sad” iron; horseshoes; mule shoes; railroad spikes; buttons.

Pausing occasionally to munch on a sandwich, potato chips and fruit, he collected those unburied treasures, stored them in four or five cardboard boxes and, just recently, returned them to the source.

“I want to emphasize that I never did any digging,” said Juergens of Jackson. “Erosion in certain areas would uncover materials that weren’t buried deeply. Construction workers on campus would often dig something up – the railroad spikes, for example.”

Last fall, he ceded his discoveries to Dr. Ralph Didlake, associate vice chancellor for academic affairs and director of the Center for Bioethics and Medical Humanities.

“David Juergens, an engaging and kind gentleman, holds a deep repository of UMMC history,” Didlake said.

“As one of the keepers of institutional memory, he reminds one of the final scene in ‘Fahrenheit 451’ in which individuals have memorized banned books and have become the narratives.

“In a very real way, Mr. Juergens and his long memory embody an important piece of our story.”

‘LONE SOLDIER’

That story contains memories especially close to Juergens’ heart: remnants of final resting places. “I’ve been interested in cemeteries from early childhood,” said Juergens, who’s in his early 80’s.

“Usually, parents don’t want their children to know that people die. I wasn’t brought up that way,” said Juergens, whose father was a minister. “He was ill for many years; he was 34 when he died.” Juergens, an only child, was 3.

In days past, he said, it was fairly common for relatives to spend a spring day together visiting family gravesites and paying their respects. “You might even have a picnic,” he said.

“So it became kind of natural for me to do that.”

At the cemetery, a place normally representing loss and separation, he felt closer to his family and to the father he never really knew. He came to appreciate history, not just his, but everyone’s, and the lives of those who passed.

These feelings grew as he did, from his childhood in St. Louis and Denver and into his adulthood, when he earned a master’s degree in psychiatric social work.

As an employee with the Kentucky Department of Mental Health, though, he began looking for a new career; this led him, in 1968, to respond to a search for an acquisitions librarian, one with a background in behavioral and social sciences. That’s how he came to UMMC.

At the Medical Center’s Rowland Medical Library, Juergens became a fixture, as much as the medical textbooks – and just as particular.

“David’s a lone solider, very private, but very thorough,” said Virginia Segrest Hughson, UMMC associate professor emeritus of academic information services, who was and Juergens’ supervisor for a time.

“He was polite and caring, and very proud to be part of the Medical Center. When he had a project, he did it to perfection.

“When we moved [to the Learning Resource Center] from the old library on the second floor near surgery, we had an inventory the next year. And we couldn’t find some shelving. I told David to write it off. We’re talking about some old, wooden shelving.

“Well, it was his responsibility, and he was determined. It probably took him a few months, but he found that dadgum shelving.”

GRAVE EXPRESSIONS

Juergens retired in 2012; in those four-plus decades, he made his mark, helping the School of Nursing develop its first Humanities Collection, single-handedly chronicling the library’s artwork, managing book sales for Friends of Rowland Medical Library for 16 years, helping document more than 180 distinguished women in the health sciences for the 2008 traveling exhibit: “The Changing Face of Medicine.”

In 1975, just before the School of Dentistry’s debut, he established the first collection of dental textbooks at UMMC. And, for years, he took those long walks known to his colleagues and friends.

“The campus was smaller at one time; there was more room for him to wander around,” said Walter Morton, a retired associate director of the library, who was also Juergens’ supervisor for a while.

“He was kind of an amateur archaeologist. He would visit the area that had been the graveyard where people from what used to be the mental institution were buried.”

That institution was the extinct Mississippi State Hospital for the Insane, originally the Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum, which operated from 1855 until 1935.

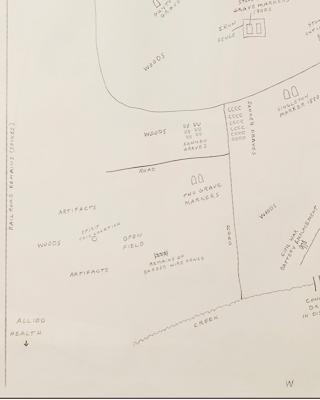

In his ramblings across the northeast corner of the campus and beyond, Juergens ran across shades and shadows of burials. Some 10,000 deaths were documented at the asylum, and the bodies of thousands of patients still lie under ground in anonymous graves; dozens of coffins have been uncovered during construction work and many more have been detected by radar scans.

Members of the Asylum Hill Consortium, directed by Didlake, are archiving the graves and memorializing the people they hold.

Juergens found signs of other burials as well – depressions in the earth; a marker from, he believes, the 1880’s bearing the name Singleton.

Apparently, there was also a Potter’s field – a cemetery for paupers – on this land, and a graveyard for Cade Chapel Missionary Baptist Church, a house of worship for former slaves. Even Civil War soldiers may lie at rest near an earthen parapet.

Juergens also believes victims of a yellow fever epidemic are among the dead; in the late 1800’s, thousands of Mississippians succumbed to the disease.

Wherever he looked, he said, he found evidence of settings “where people were buried who weren’t wanted.”

SPIRITS AND TRAINS

Many markers and gravestones have been preserved; you can visit them in the Medical Center Cemetery, just south of Lakeland Drive, not far from St. Dominic Hospital, where Juergens roamed.

“I seldom saw anyone else back there,” he said, “unless they were cutting through to go to St. Dominic. “Otherwise, the site was quite deserted for many years, more or less forgotten.”

On one outing, he found “these inexpensive, plastic flowers that were very old and very weathered,” he said. He stumbled onto a grave marker formed by round, six-inch stones.

“I sure wish I had taken photographs,” he said. “I want to kick myself for not doing that.”

Among the most melancholy finds are bits of slate roofing, apparently from the asylum; a uniform button engraved with a sketch of an old railroad locomotive; and a “spirit coin” – worn a chain or string as an amulet. In this case, it was an "Indian head" penny – a coin last minted in 1909.

“Unfortunately,” Juergens said, “the hole [for the string] was drilled right through the date.”

By 1990, the year Morton arrived, progress was putting a crimp in Juergens’ lunchtime quests. “He couldn’t do quite as much,” Morton said. “Too many buildings and too much concrete.”

But he made the most of the less cluttered years – more than 30 of them, Juergens said, in a serial artifact hunt that began once he learned that an institution dedicated to saving lives was also a domain of the dead.

Though he did not document the fruits of that chase with photographs or notes, he did draw from memory a map marking the location of various graves. This drawing, resembling a “Lord of the Rings” sketch of the Shire, he also donated.

“I gave everything to the Medical Center, except a big, clunky piece of brick work – because it’s so large,” he said. “They can have that, too, if they want it. And I kept one horseshoe, for good luck.

“I’m getting older now and can’t take all these things with me when I go. The Medical Center is a fitting place for them. That’s where they belong. Maybe they will have a long life now, and a permanent home.”