New procedure to gauge fertility less painful, more accurate

Ashley Maryland's two medical procedures done to figure out why she was having trouble becoming pregnant were like night and day.

“It was awful,” Maryland, a Vicksburg resident, said of the hysterosalpingogram, or HSG, performed there in 2013. “It was overwhelming pain, and there was nothing I could do. It was the worst pain ever.”

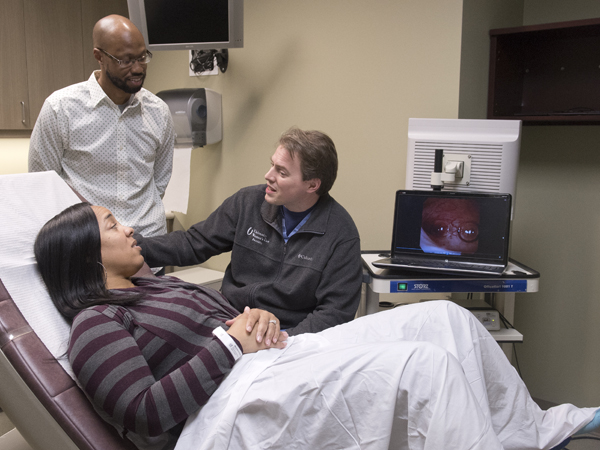

But her most recent procedure, performed in 2015 by Dr. Preston Parry, University of Mississippi Medical Center associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology, was anything but.

“I anticipated it hurting. I prepared myself for it. But it didn't hurt at all, and I got to watch it on a screen,” Maryland said. “It was as lovely as it could be for that type procedure.”

Not just patients, but their doctors despise HSG, a test that's been used for decades to examine a woman's fallopian tubes to see if they're blocked. It uses a combination of X-rays and dyes to take a picture of the uterus and typically is done in a hospital. Parry, a reproductive endocrinology specialist and chief of the Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, has come up with a technique that minimizes discomfort while also being more accurate, faster, cheaper, safer and convenient.

It's called the Parryscope, not a piece of equipment, but instead a specific procedure that replaces HSG. During HSG, a physician inserts either a stiff or flexible tube into a woman's cervix on the way to her uterus. Dye is passed through the inserted tube; if the fallopian tubes are open, the dye will flow through, but if they're blocked, it won't.

Patients don't receive anesthesia, painkillers or drugs to deaden the affected area.

“There are so many women who say it's the most painful thing they've been through,” Parry said. “Women have told me it was worse than childbirth.”

What's different about Parry's procedure: He uses a narrow, flexible fiber-optic camera, saline and air to determine if the saline and air bubbles can enter the fallopian tubes and if the uterus is receptive to pregnancy. Dye isn't used at all. “If the air bubbles don't go in, the sperm may have trouble getting in, too,” Parry said.

“The camera is the width of a coffee straw,” he said. “We use technology so small and gentle that the speculum for a Pap smear is typically worse.”

During her first procedure, Maryland said, “one of my tubes was closed, and they forced the dye through it. It was 100 times more painful than the Parryscope. I'll never forget it.”

Parry presented findings on his Parryscope procedure at the October 2015 meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

To his knowledge, Parry said, no one had previously published data validating the use of a hysteroscope to observe air bubbles and saline for fertility testing. He presented his procedure in October 2015 at a meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and also at the Open Endoscopy Forum at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“The input was very favorable,” he said of physicians' reaction to his procedure. “They wanted to know more. The data shows it's as accurate, if not more accurate, than anything else out there, and light years more gentle.”

The Parryscope is performed by Parry; Dr. John Isaacs, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology; and their team at the University Physicians Women's Specialty Care Clinic in Flowood.

“The biggest thing I see is that patients having the scope here in the office generally are more comfortable,” said Vicki Butler, charge nurse for the division. “They are in an environment that seems a little safer to them. They know the nurses and staff members who are involved in their care.”

While saline used in the Parryscope generally seeps back out of the uterus' opening because of the thin scope used, dye used in the HSG procedure stays in the uterus longer, Butler said. “Either it goes out the tubes, or it stays in the uterus because the fallopian tubes are blocked. There's pressure, and the pain occurs when the dye is placed in the tubes.”

An abstract Parry published in September 2015 showed that 88 percent of women undergoing Parryscope have mild to no discomfort, 10 percent have moderate discomfort, and 2 percent have severe discomfort. His first study of the Parryscope showed that 0.4 percent of women having the Parryscope technique reported extreme discomfort as opposed to 42 percent of those who described that level of pain with HSG.

There are risks associated with both HSG and Parryscope. A woman with a history of gynecologic infections should inform her doctor, who might want to give her antibiotics before the procedure. Vasovagal reactions are rare, and in the case of a Parryscope, it's possible that air bubbles could travel to the lungs, causing an air embolus. “Theoretically this could occur, but in practice and to our knowledge, it has never happened,” Parry said.

Parry said that he continues to research the procedure. Over the past couple of years, he said, he's done the relatively unknown procedure about 500 times. Parry said the procedure, although patented, isn't a money-maker in itself. “They may not have the equipment, but I could teach most OB-GYNs how to do this in 10 minutes,” he said.

“The reality is, if you can have a test that's more accurate, gentler, cheaper and faster, would you do it? Patients overwhelmingly prefer it,” he said. “It's replacing a test that people passionately hate, and there hasn't been a viable alternative until now.”

Photos

| High Resolution Medium Resolution Low Resolution |