The proof is in the moms and newborns: STORK is saving lives

When a woman expecting twins walked into the emergency room at Simpson General Hospital in Mendenhall, she was in labor and her babies were premature – and breech.

A rural ER is not where deliveries should happen, especially a high-risk breech in which the baby’s hips or feet, not head, are positioned to come out first. “She knew she was having twins, but didn’t know anything else. She had very little prenatal care,” remembered Jennifer Boutwell, Simpson General’s lead emergency room nurse practitioner.

In the absence of obstetrical providers, Boutwell’s job was to keep safe both mother and babies. She did that, thanks to training through a University of Mississippi Medical Center program that teaches rural first responders and ER providers how to recognize pregnant moms in crisis, and how to stabilize them and their baby until they can get to a higher level of care.

The life-saving training, created through UMMC’s Mississippi Center for Emergency Services and led by a team that includes UMMC maternal-fetal medicine specialist Dr. Rachael Morris, is called STORK. That’s short for Stabilizing OB and Neonatal Patients, Training for OB/Neonatal Emergencies, Outcome Improvements, Resource Sharing, and Kind Care for Vulnerable Families.

STORK just concluded its first year, training upward of 450 emergency responders and ER providers during 30 four-hour sessions. It’s received $500,000 in second-round grant funding from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation that will carry it to September 2025.

Morris “told us to care for the mother first – to get her stable – and then worry about the babies second,” Boutwell said. “In STORK, we learned how to check the cervix for dilation. Her cervix was only between five and six centimeters, so we knew we had time for the 25-minute transport to UMMC.”

Before STORK, Boutwell said, “I would have known to check her for hemorrhaging, but I would have had no idea what the danger signs were, and no idea how dilated her cervix was.

“It saved three lives that day,” Boutwell said of STORK.

Pregnant and post-partum Mississippi moms die needlessly from hemorrhage, hypertension and cardiology issues because many rural providers and first responders simply don’t have the training to save them.

“Over the course of the year, the need for all of these people to be trained became more eye-opening,” Morris said.

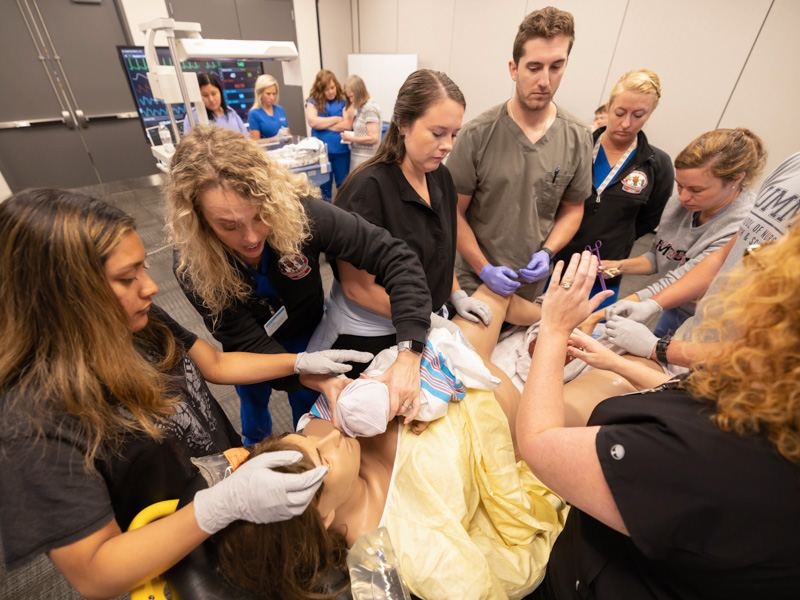

Without a doubt, the training is saving lives. Its centerpiece is a simulation pregnant mom named Victoria and a simulation newborn, Super Tory. The vital signs of both are displayed on real-life hospital monitors. Victoria breathes, talks, grunts and is overall not a happy camper.

“The baby is coming!” she yells, sometimes followed by a terse “Don’t touch me!” as those being trained gather around her gurney. When Super Tory is born, she emerges greased down and slippery to simulate an actual birth, then walked to an isolette feet away.

“We are giving them the key educational pieces to handle the most common emergencies they’ll be faced with, and we are using state-of-the-art simulation to reinforce that education,” Morris said.

STORK originally targeted ER providers at rural or critical access hospitals. “But, it became apparent very early that rural EMS workers needed the training and wanted the training,” said Kace Ragan, special programs manager at the Mississippi Center for Emergency Services.

“What we found is that in some of the very small places, EMS workers were working in their local hospital emergency rooms as well.”

When MCES contacted a handful of small hospitals in 2022 about STORK training, “we didn’t have any idea what the response would be,” Ragan said. “Word of mouth took over, and it took on a life of its own.”

They take STORK on the road, loading up simulators and supplies and assembling it onsite, then breaking it down and driving back to Jackson. Grant-funded Victoria is expensive – about $100,000 – and must be handled very carefully.

“Rural Mississippi hospitals don’t have education budgets or travel budgets. They don’t have enough staff to give them time off to drive to training,” Ragan said. “We teach on their turf.

“We’ve set up in an unused operating room. We’ve set up (classroom training) in hallways because there was no other space.”

“Everyone in a location where these patients might show up has to recognize the abnormalities and their significance,” Morris said. “A 21-year-old who comes to the ER with chest pains and shortness of breath and no other risk factors might be dismissed.

“But when you add to it that she delivered just two weeks ago and her blood pressure is 150 over 100, that’s a life-threatening emergency. A provider could miss a critical diagnosis if they’re not trained.”

“From what I have heard from our ER and ambulance staff, this was the most impactful training they have ever taken,” said Mike Cole, chief compliance officer at Covington County Hospital in Collins, a sister hospital to Magee General Hospital and Simpson General Hospital in Mendenhall.

“What they liked about it was the amount of hands-on training,” Cole said.

The classes are critical, Cole said, not because ED and ambulance staff treat large numbers of high-risk pregnant or post-partum moms and their newborns.

It’s because they treat so few.

“That’s the danger,” Cole said. “We can’t gain or maintain steady confidence. STORK classes push up the confidence and competencies.”

It’s one of the reasons Mayra Sanchez, a paramedic with Lifecare EMS in Noxubee County, took part in a May 16 training at MCES. “We don’t really do a lot of OB emergencies, but now, at least I’ll be prepared,” Sanchez said.

Registered nurse educator Leslie Cannon leads trainees through a hallway lined with long tables bearing plastic cervixes in different states of dilation, a red liquid-soaked pad for them to estimate how much blood a mom has lost, and a pelvis-only mannequin to practice the steps taken in a delivery.

“We want this to be a mirror image of what they will see,” Cannon said.

Emily Wells, a nurse practitioner and supervisor of neonatal transport, educates using full-term Super Tory, who often is born “stunned,” or slow to breathe, move or cry. That means trainees must make a quick decision, such as using a CPAP device to help her breathe, or even intubating her.

The training includes resuscitation of premature newborns half Super Tory’s size. “You need to be ready and on your game. You’re thinking, ‘I do not want to hurt this child,’” Wells said.

“But I see them become more and more comfortable. At the end of the day, they seem more confident in their skills.”

Senior-level Emergency Medicine residents who work part-time at small hospitals have been STORK- trained during the past year, said Dr. Tara Lewis, a STORK team member and assistant professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine. “The hands-on training gives them that muscle memory and reassurance,” she said.

“That‘s exactly what STORK was designed for: for non-obstetric providers to feel more comfortable taking care of OB patients,” said Lewis, a labor and delivery nurse before becoming a physician.

Going forward, STORK will offer more enhanced training to first responders faced with a mom in labor. “They’re the ones who see what happens on the couch cushion or in the back seat of a car,” Ragan said.

“These stories and first-hand reports that the education STORK provided changed an outcome … It’s the motivation that we’re on the right track, and what we’re doing is working,” Morris said.