Creation of ’55 medical school due to spine-tingling courage

NOTE: This article originally appeared in the Summer 2017 issue of Mississippi Medicine, the semi-annual alumni magazine for the School of Medicine.

In a scenario no self-respecting Hollywood screenwriter would pen, a decision to build a new hospital and educate more doctors lay in the hands of a convalescent.

Her name was Zelma Wells Price, a Mississippi lawmaker who was wheeled into the House chamber on a stretcher to cast her vote on a proposal to create a teaching hospital and four-year medical school in Jackson.

Former Mississippi Gov. William Winter, now in his 90s, was in the House that day in 1950, representing his home county, Grenada. In an interview he gave in May, he remembered Rep. Price.

But what he remembered more vividly, he said, was a galvanizing speech given by a young legislator that same day, an act of courage at the time, Winter said, that made “that country boy from Taylorsville a hero to me.

“What happened that day may not look like much today, but I’m telling you, it was a revolution.”

Fifty years beyond the 19th century, Winter said, it brought Mississippi into 20th – scaling the ever-present mountains that always seem to stand its way: economics, politics and matters of race.

Unhappy mills

The School of Medicine that would open 10 years after World War II ended is the descendant of one that appeared 11 years before World War I began.

For years after the two-year school in Oxford debuted, though, medical students in the state had choices.

Meridian had a school. So did Vicksburg: The University bought the 150-bed Charity Hospital, renamed it University Hospital, installed classrooms and such, and began edifying its nine third- and fourth-year students in Sept. 1909. It lasted a year.

For the bulk of the last century’s first five decades, students who finished two years of medical school in this state had to light out for cities like Memphis and New Orleans to complete their M.D.s.

“They left Mississippi, graduated elsewhere, established themselves there and, often, stayed where they were,” said Dr. Owen “Bev” Evans, UMMC professor emeritus of pediatrics.

As Evans records in his book, “A History of Mississippi Pediatrics,” the state did issue a grant of charter for a medical college in Meridian as far back as 1882, but the school never got off the ground.

Lifting off successfully, in 1906, was the Medical College of Mississippi in Meridian (later, Meridian Medical College), whose clinical teaching facility was the Matty Hersee Hospital; it endured about six years.

It was a four-year program, but, apparently, wasn’t choosy about its applicants, did not like mixing students with patients so much, and registered the lowest pass rates for the state’s 64-question licensure exam, which required only 58 correct answers.

Eventually, the Meridian college collided with the nemesis of similar schools of that era: the Flexner Report. Summarizing the state of medical education in North America, Mr. Flexner wasn’t charitable toward the physician-owned institution in the Queen City.

“It was a diploma mill,” Evans said. So were a number of other medical colleges in what was considered a doctor-glutted nation at the time. The report, along with the state Board of Health, essentially, closed down Meridian’s for-profit establishment, the fate of many comparable concerns.

Flexner was kinder to the one in Oxford, declaring it “distinctly creditable.”

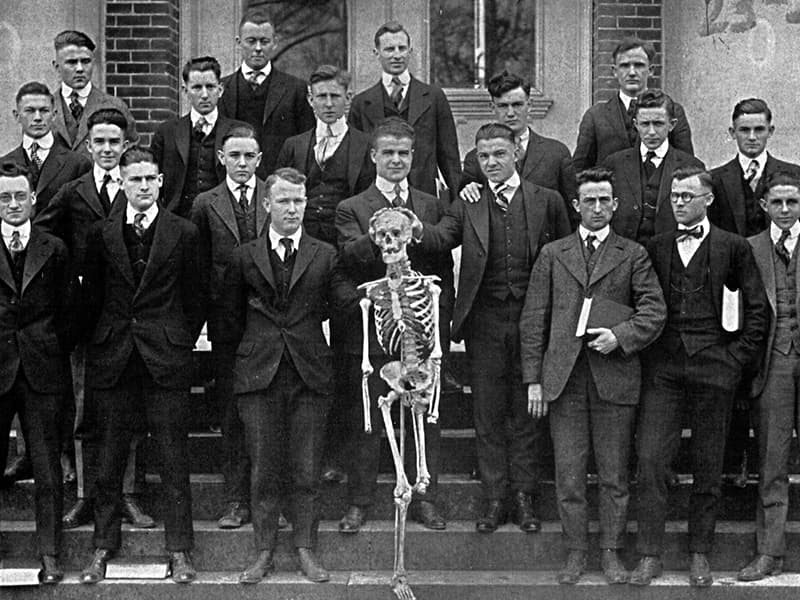

That school was launched at Ole Miss 114 years ago with a budget of $27,000. (Real wages in 1903: $1.88 per day.)

It admitted 16 students, who had to be at least 16 years old, present written testimony to their moral rectitude and prove they had been able to get through a college or a normal school or, at least, a high school.

Students took courses in anatomy, physical chemistry (biochemistry) bacteriology (microbiology), pharmacology and physiology. They earned Medical Certificates that qualified them for entrance into four-year programs. Many found careers in academic medicine: 124 between 1911 and 1955.

The Lyceum was the school’s home its first three years, followed by the new Science Building until 1923, and, successively, the Chemistry and Pharmacy Building and Guyton Hall.

In 1954, the year the future Dr. Ed Smith was admitted, “medical students were housed in the athletic dorm, before they were moved,” he said.

“The school was scattered all over the campus. There was no single medical school.”

Change was afoot.

Kill bill

In 1943, the Mississippi State Medical Association got in on the act, declaiming for the creation of a four-year medical college “free of political domination to ensure practical operations.”

Seven years later, the legislature joined the cast of thousands delivering the same line.

Which is an incredible shrinking, Cliffs Notes version of events. For more drama, stay tuned:

“We had been trying for years to get a four-year medical school,” said William Winter, exasperation flitting across his features even now, a lifetime later. “My first year in the legislature, we were not successful.”

That was 1947. “The conservative Old Guard said we’d have to raise taxes,” Winter recalled. They said it would lead to racial integration.

“We were still fighting the Civil War,” said Winter, who would lead a battle for education reform in the 1980s as governor.

The four-year faction believed the facts, and needs, were on its side: Mississippi needed more physicians in rural areas. It needed to create post-graduate training for pediatricians. It needed more community health services. It needed more localized care for premature infants.

These were the findings of a 1946-47 joint survey by the state and national chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, the State Department of Health and federal agencies.

“Infant mortality was high in Mississippi,” Evans said. “We also needed more surgeons, more interns, a lot of things we weren’t providing.”

All of that may have a bearing on the decision to find the money for a new, four-year school Evans said.

All that, and a man who took the high road, and a woman laid low on a stretcher.

Four on the floor

Among the various champions of a new school were students attending the old one.

In the spring of 1950, around the time Jay Leno and Stevie Wonder were born, those students arrived in Jackson to petition lawmakers.

“They asked me if it was all right,” said the late Dr. David Pankratz in a talk he gave in 1975. “I told them if their parents were taxpayers, they had a right to tell the legislature what they thought," recalled Pankratz, the school’s first dean.

“It was quite a sight, the floor of the legislature dotted with future doctors in white coats talking up the four-year school,” he told a UMMC audience, as reported in The Clarion-Ledger.

At the Hotel Heidelberg in Jackson, doctors, legislators and other citizens had also talked it up or down. The open forum was organized by a group of politically active women. It was women whom Pankratz credited with keeping the four-year fervor alive.

One of those women would eventually be driven from Jackson back to her home in Greenville in a Wells Funeral Home ambulance. She was still alive, and would live many years longer.

Her name was Zelma Wells Price, a native of Calhoun County. An attorney, she had been elected to the legislature in 1943.

She became known as the author of the Mississippi Youth Court Act, the first female judge in Mississippi, a jurist who put women on county court juries when the state officially barred them, and a foe of discriminatory laws.

Sometime in late 1949 or early 1950, she was in a car accident that injured her back. That’s why on a spring day 67 years ago, she entered the House chamber horizontally.

And she left, you might assume, ecstatically: Newspaper accounts from the day credit her with bringing the medical school appropriation bill out of committee after what Winter described as a “bitterly fought battle.”

“I swung three votes over after I get there,” Price said in an April 1950 article in the Delta Democrat-Times. Although her entrance “might have been a little dramatic,” she added.

Her nurse, identified as “Mrs. E.R. Williams, R.N.” told the DDT, “It was the most unusual and thrilling experience I've had since being ‘capped’ as a nurse. Everyone gives her credit for getting the bill out of the committee.”

It escaped with its life by one vote.

And then, it was hoped, the Lord, and Blaine Eaton, would provide.

Winter of content

“It was one of the finest speeches I’ve ever heard,” Winter said.

“Here was a freshman legislator taking on the most powerful politician in the state, Walter Sillers.”

House Speaker Sillers became a Medical Center supporter, but on that day, Winter said, he threw his weight in front of the bill. And Blaine Eaton got between them.

“He wasn’t a doctor, but he had a feeling for people,” Winter said. “He wanted to make sure every boy and girl in Mississippi who wanted to be a doctor could become a doctor.

“Blaine Eaton stood up on the floor of the House and said, ‘They say – THEY SAY – we can’t afford a four-year school,’” said Winter, recreating Eaton’s oratory. “‘I’m telling you we can’t afford NOT to have a four-year medical school. We’re sending young men out of state and they’re not coming back.’

“It was the climactic, decisive speech,” Winter said. “We had this brain drain of bright young students who wanted to stay here, but couldn’t, if they wanted to graduate from a medical school.

“That’s what broke the ice. That’s when Mississippi decided to join the Union. And young people who had not had the opportunity before could stay here. We said, ‘We’re going to provide a medical education for all our citizens.’”

The original design for the Medical Center was for an integrated facility, according to “Pressure from All Sides,” a history of UMMC’s early years. The barriers arose later and stood for years, until segregationists’ fears came true – the result of James Meredith’s integration of Ole Miss, the administration’s concerns about academic accreditation and employment laws, and other factors.

But that vote in 1950, Winter said, “was the beginning of the end of segregation in our education system. It led the way to further integration at our institutions of higher learning.

“Of all the things I was involved in during my years in the legislature, it was probably the most dramatic measure we passed. Even segregationists recognized that it was the right thing to do – economically and as a matter of human rights. It also opened the door for poor whites.”

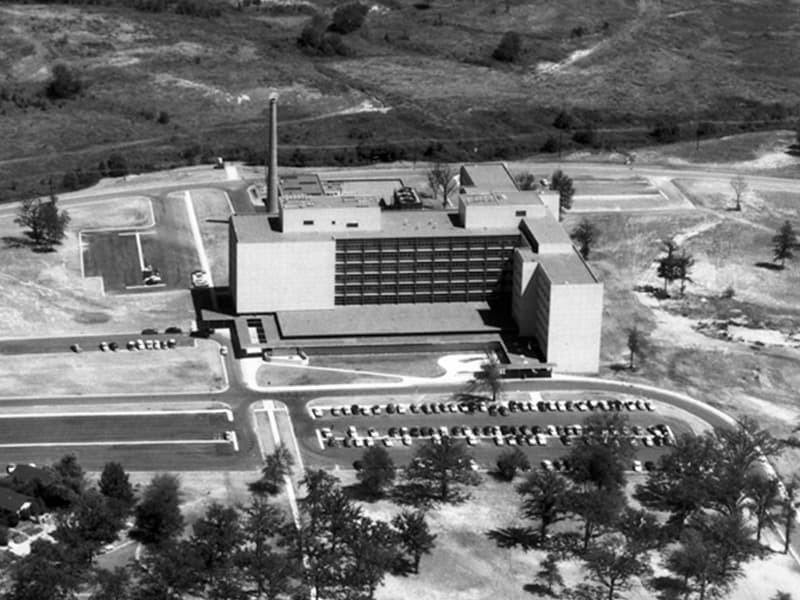

Legislators liberated $4.5 million for construction, which totaled $9 million. On a freezing December morning in 1952, the ground at the former site of an “Insane Asylum” was hard and cold; dignitaries armed with shovels, in an age-old ceremony, broke it anyway.

The “revolutionary” landmark opened, on July 1, 1955.

“I’m so proud of it,” Winter said. Only about a three-minute drive from his home in north Jackson, it is close to him in other ways.

In January, while walking his dog on an icy driveway, Winter slipped and fell, suffering a concussion. An ambulance took him to the place his vote helped build; it wasn’t the first time he was a patient there, he said.

“I’ll always be a supporter of the Medical Center – and its medical school. It saved my life, twice.”

The fame of Price

In February 1998, a man who had been described, variously, as graduate of Ole Miss and the George Washington Law School, a farmer, a cotton buyer, and a “country boy,” was the subject of a bill in Congress designating the Blaine H. Eaton Post Office Building on Highway 28 E. in Smith County.

Although the transcript from the Congressional Record does not mention the vote that made him William Winter’s hero, it does say, “The bills he passed in Mississippi … are still benefiting the people of that State today.”

Eaton had died in 1995, a farmer and country boy who did some of his best work in the city.

Two decades earlier, on Feb. 24, 1974, Zelma Price died at the age of 75. Her obituary in the Delta Democrat-Times recapped her 1950 heroics, and an editorial commended her “many trail-blazing achievements.

“All of us were fortunate that her life among was so long and full,” the tribute read.

Decades earlier, an article about Price noted that her friends called her “Little Zelma” – but the impact she made on medical education and Mississippi history was anything but small.

SOURCES: “Promises Kept” by Janis Quinn, “A History of Mississippi Pediatrics” by Dr. Owen “Bev” Evans, “Pressure from All Sides” by Dr. Robert Currier and Maurine Twiss, “Medical Education in Mississippi: A History of the School of Medicine” by Lucie Bridgforth, The Delta Democrat-Times, The Clarion-Ledger, National Bureau of Economic Research