New guidelines call for more non-opioid pain relievers

Too often, the nation's top federal health agency says, doctors put an opioid prescription into the hands of patients who complain of chronic or one-time pain or those who in truth don't hurt.

New guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on dispensing the most powerful and addictive painkillers are tough for some doctors and patients to accept, even if alternative treatment is available, says a University of Mississippi Medical Center psychiatrist.

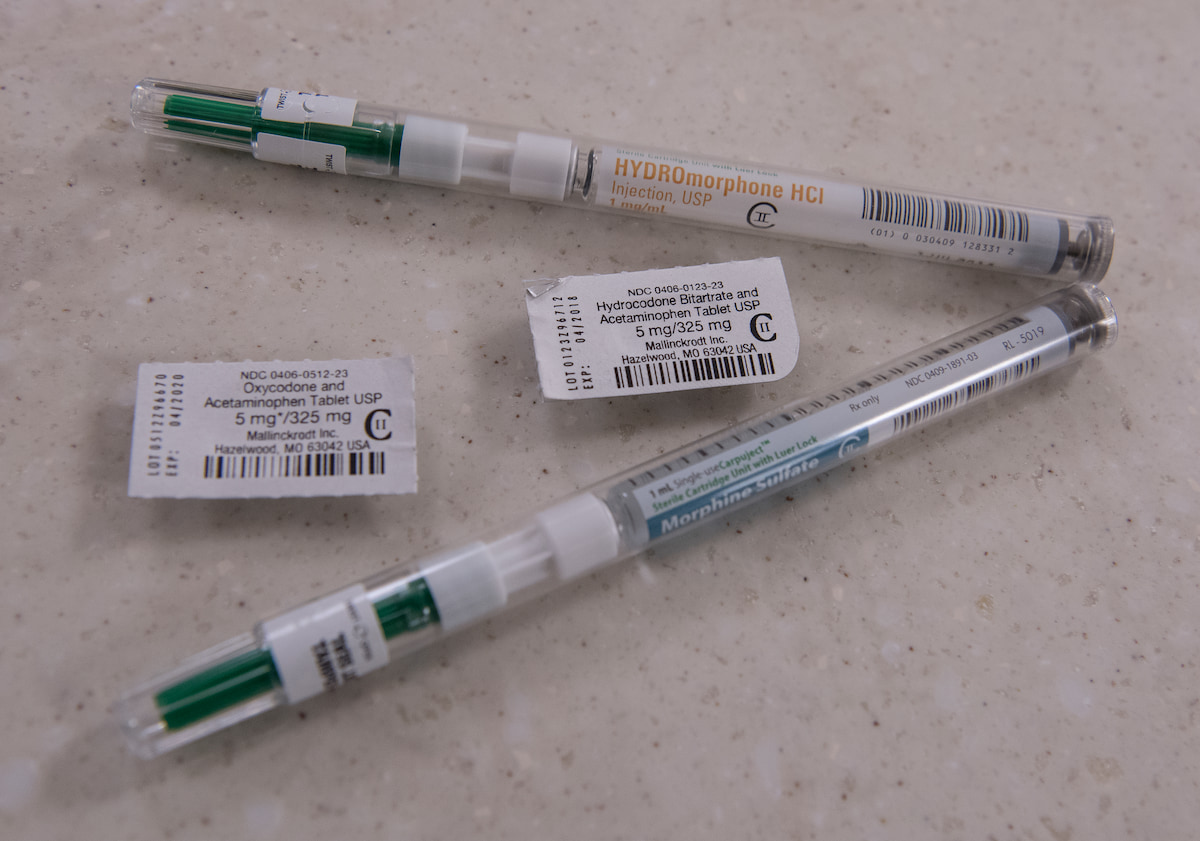

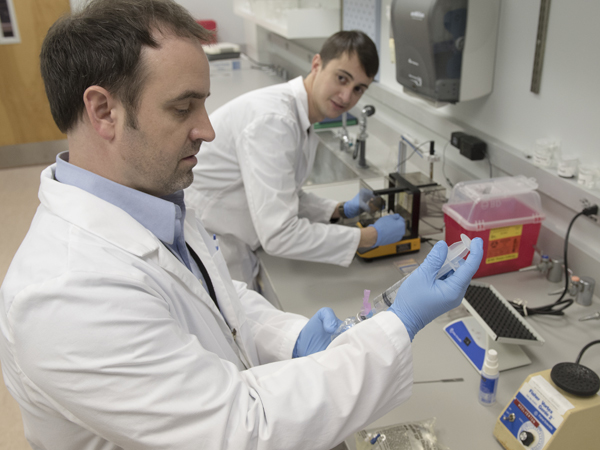

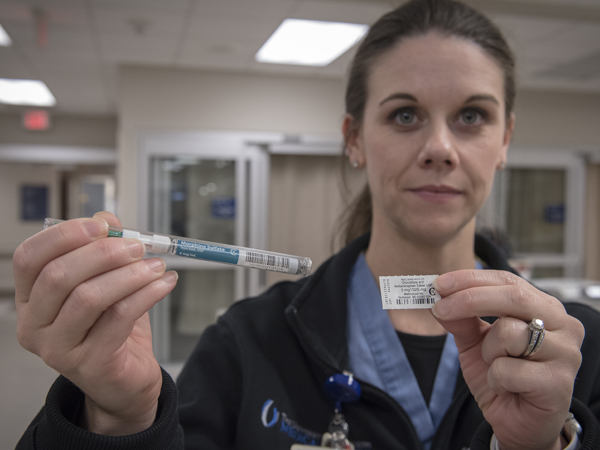

UMMC addiction experts are addressing the crisis head-on, performing National Institutes of Health-funded research to alter the formulations of prescription opioids so that they have less misuse or abuse potential.

“The CDC is making these recommendations because the number of doctors prescribing opioids for addicts is pandemic,” said Dr. John Norton, professor of psychiatry and one of only two practicing physicians in the state who have subspecialty board certification in headache medicine.

Among them are the following:

- Doctors should try safer and more effective treatments before resorting to opioids - for example, exercise, anti-depressants or pain drugs that aren't opioids.

- If a doctor believes an opioid is necessary, it should be prescribed in the lowest dose possible for the shortest time possible. It should be an immediate-release dose because it's much easier to get addicted to extended-release medications.

- Doctors should weigh the risks, among them overdose or addiction, before prescribing opioids and should talk to their patients about their goals for treatment and plans to taper off for good.

- And, for acute pain that's caused by an injury or recent surgery, doctors should limit a prescription to three days. Prescribing for seven or more days is rarely necessary, the CDC says.

Although the CDC's retooled guidelines for physicians in primary care practices were released in March 2016, they're now beginning to gather steam. They don't target patients receiving cancer or end-of-life care, but instead patients who have chronic pain or pain from a short-term medical problem, or who seek opioids because they're addicted or want to sell them on the street.

“Opioid addictions have to start somewhere, and usually that somewhere, for the vast majority of addicts, is a relatively minor painful medical problem or injury,” said Dr. Alan Jones, chairman of the Department of Emergency Medicine, which oversees the Medical Center's Emergency Department that sees about 70,000 adult patients a year.

In his practice, Norton sees dozens of patients who want opiates for pain that isn't acute and isn't caused by cancer. He prescribes drugs that can be addictive only as a last resort in cases where he believes a patient truly needs them.

Alternatives include physical activity and drugs that address depression, or non-opioid pain medications such as Neurontin or Lyrica. “Forty to 60 percent of chronic pain patients are depressed,” he said.

Medicines with no addictive dangers can also be used in combination, with physical therapy or an exercise regimen, Norton said. He said doctors must do a better job of separating the patients who don't have legitimate pain from those whose pain needs some form of treatment.

“Patients sometimes try to pressure doctors. You give them medications that take a while to work, and they'll say it didn't work. I understand that if you're a family doctor, you might give in. You only see a patient an average of seven minutes, and patients abusing opioids tend to come at the end of the day,” Norton said. “But, you pay a price.”

That's also true of pain management clinics where opioids are routinely prescribed, increasing the risk of addiction. “It's hard if that's your livelihood to be objective,” he said of doctors specializing in pain management. “A lot are well-intentioned, but they don't have to follow up with the problem.”

Norton said he's heard it all: A patient lost his meds or accidentally dropped them in the toilet. They're about to travel and need some for the road. “They use them all up before the next prescription, and then they're calling you,” Norton said.

“I tell them that if your house is burning down, you'd better go in and get your opioids because I'm not refilling that prescription,” he said.

“A huge problem with prescription opioid abuse is that people who become dependent exhaust their doctor-shopping options, and then they start buying them on the streets where an oxycodone pill could cost $30,” he said. “If they're unable to afford it, they transition to heroin because it's a much cheaper alternative, and the illicit market has capitalized on this increased demand with greater availability of heroin. If we can't get abuse of these medications under control, we will continue to grow the heroin-using population and all of the problems that come with it.

“And as if that weren't bad enough, many are now buying heroin that is unknowingly mixed with synthetic opioids that are cheaply manufactured by rogue chemists, similar to what we've seen recently with 'spice' and 'bath salts',” Freeman said.

His research strives to make legitimate users of opioids find them less desirable if they abuse them. That's achieved by adding substances that produce nausea or other bad side effects to the prescription opioid if it's taken in higher amounts than prescribed, but not affect its value as a pain reliever for legitimate uses.

Instead of getting the feeling of euphoria and craving more of the drug in order to maintain or increase the high, the opioid user would feel the opposite. The incentive to use it would go away - and hopefully cut off a pipeline to that illicit market.

“The long-term goal of the research is to provide physicians with a new opioid pain medication that can be used to treat pain without having the risk of abuse liability in their patients,” Freeman said. The work is funded by a five-year, $2 million NIH grant.

Fewer deaths from opiates also is a top goal, CDC director Thomas Frieden said in announcing the new guidelines. About 40 people die each day in the United States from painkiller overdoses, the CDC estimates.

“Dealing with the addiction crisis will take physicians clamping down on prescribing habits as well as patients recognizing narcotics are not needed or indicated for minor pain problems or long term use,” Jones said. As a medical community, he said, physicians need to direct patients to more over-the-counter pain medications such as ibuprofen and acetaminophen.

“I feel bad for this population. I feel like we as physicians contribute to the problem,” Norton said. “That's why the CDC came out with these guidelines.”

FAST FACTS

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show:

- From 1999- 2015, more than 180,000 people died of overdoses related to prescription opioids.

- An estimated one out of five patients with non-cancer pain or pain-related diagnoses are prescribed opioids.

- Since 1999, sales of prescription opioids in the United States has quadrupled.

- Nearly 2 million Americans abused or were dependent on prescribed opioids in 2014.