FIXing genes: a first at UMMC

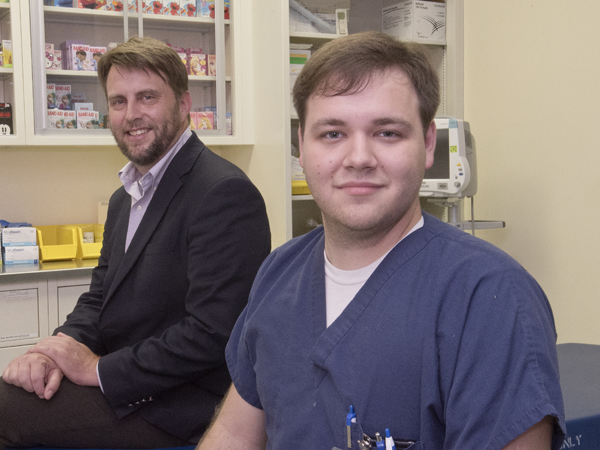

This spring, Ryan Hallock helped bulldoze 10 acres of land. He felt sore afterwards, the usual aches and pains that come from hard labor, but otherwise fine.

“Last year if I did that, I would be down for a whole week with joint pain,” said Hallock, 23. He has hemophilia B, a genetic disorder that impairs blood clotting. In Hallock's case, it also caused recurrent bleeding in his knees and ankles.

In December, the Jayess resident came to UMMC and was the first person - in the world - to participate in a new gene therapy clinical trial to treat hemophilia B. The results are promising.

“The patients have experienced no bleeds, no immune response to the treatment and an improved quality of life,” said Dr. Spencer Sullivan, an assistant professor of pediatrics and hematologist who treated Hallock. “This therapy looks like the leading candidate for hemophilia B.”

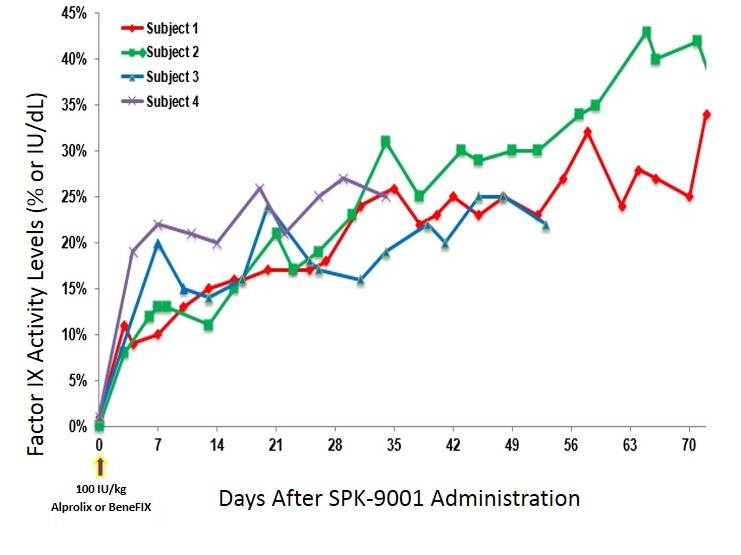

Sullivan presented early data from four subjects, Hallock included, at the European Hematology Association's 21st Congress in Copenhagen, Denmark on June 11.

All four patients have severe or moderately severe hemophilia B. Their bodies produce less than two percent of the average amount of factor IX (FIX), a protein that helps blood clot. After a one-time treatment, the group maintained an average 30 percent of normal FIX several weeks later. That's enough to control bleeds from most injuries. Forty percent FIX is considered sufficient for normal clotting.

“What others at the conference were amazed by was the reproducible dose response,” Sullivan said. The subject's FIX levels ranged from 27 to 35 percent. “No other study has consistent shown data thus far.”

Hemophilia B, caused by a mutation on the X chromosome, affects about 5,000 men in the United States. Men are much more likely to have the disease because they only have one X; women must have mutations on both of their X chromosomes.

There is no cure for hemophilia, but people manage and prevent serious bleeds with regular FIX infusions. However, it comes at a steep cost: enough FIX to manage severe hemophilia, like Hallock's, can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars per year.

For the past few years, Hallock has self-infused prophylactic FIX twice a week to prevent bleeds. He has not used any since December.

“My insurance company actually called me to ask why I hadn't filled the prescription in months,” Hallock said.

“The idea of inserting a gene directly into a patient that would internally 'cure' them is intriguing,” said Dr. Richard Summers, associate vice chancellor for research. “It may be the future of medical management for diseases such as hemophilia and sickle cell disease.”

Gene therapy, or gene transfer, has been tested for numerous conditions since the late 1980s. There are two treatments for extremely rare conditions approved for use in Europe; none have received FDA approval in the United States.

This hemophilia B gene therapy uses a viral vector. It is not a virus, Sullivan stresses. Instead, it's more of a benevolent Trojan horse. It starts with a virus, but bioengineers remove the DNA inside, leaving the shell. The shell is filled with a FIX gene and a component that directs the vector to the liver. A patient receives trillions of these vectors through an IV. Once inside the liver, the Trojans come out of the horse: the genes use the cells to produce FIX protein to win the battle against hemophilia B.

Spark Therapeutics, a biotech company in Philadelphia, Pa. that specializes in gene therapy, developed the vector. They used a FIX gene with a unique property.

“This variant has five to ten times more activity than the wild-type [normal] FIX,” Sullivan said. “This means patients can receive a smaller dose of vector, which decreases the likelihood of an immune response.”

To date, no trial participants have had an immune response. If that happened, it could limit the treatment's effectiveness, says Dr. Lindsey George, attending physician in hematology at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and lead investigator for the study.

“This trial has the highest level of sustained FIX expression achieved and the lowest dose to succeed in a human trial,” said George. “It has exceeded expectations and I'm optimistic that this could change the way we treat hemophilia.”

This is the first gene therapy trial to be conducted at the Medical Center, Summers says. He compares the trial's success so far to other UMMC firsts, such as heart and lung transplants and HIV treatment for the Mississippi Baby.

“Since the early days of UMMC, our research efforts have been noted for innovative firsts,” Summers said. “This ranks among those achievements by our research teams.”

Sullivan says an FDA-approved gene therapy for hemophilia is still several years away. The study sites will try different doses and monitor long-term safety and efficacy to ensure that it works. However, the prospects are great.

“This study is a proof of concept that gene therapy is now at the point where we may be able to cure genetic and childhood diseases,” Sullivan said.

“This treatment has had a positive influence on the lives of each of the patients,” said George, who infused the other trial participants at CHOP. “It's heartwarming as a physician to see them engage in activities, become more active and not have to miss work because of their condition.”

Hallock started a new job on June 20. He's now a nurse at the Children's of Mississippi Specialty Clinic, where he will work with children with various acute and chronic conditions, including genetic disorders.

“I can understand and relate to patients with long-term conditions,” Hallock said. “And, I like helping people.”

He also volunteers at an annual retreat for teenagers with hemophilia. He talks with them about career choices, relationships and the importance of a healthy exercise routine. Hallock advocates for swimming. It has limited impact on your joints, he says.

“I tell them that hemophilia doesn't affect all of the decisions they make, but it can affect the consequences,” Hallock said.

He doesn't recommend bulldozing 10 acres.

Spark and Pfizer Inc. are sponsors of the clinical trial. The next public trial update will be during July's World Federation of Hemophilia congress in Orlando, Fla.