Uniform connections: Military ranks high in these staffers’ lives

The list of UMMC faculty and staff with a military history is as vast as the impact it made on their lives.

Michael Estes, for one, will forever value "the sense of discipline, integrity, and honor that was instilled in me all those years." Estes, chief human resources officer, served in the Navy for six years.

Others who served include:

- Dr. James Keeton, who recently stepped down as vice chancellor for health affairs and dean of the School of Medicine (Navy)

- Kevin Cook, CEO of adult hospitals (Marines)

- David Putt, CEO of UMMC-Grenada (Navy)

- Dr. Rick deShazo, professor of medicine and pediatrics, and Billy S. Guyton Distinguished Professor (Army)

- Dr. Gary Reeves, dean of the School of Dentistry (Army and Army National Guard)

Here are the stories of a few more.

Technical sergeant, X-ray technician and instructor, U.S. Air Force and Air Force Reserves, retired

More than 60 people arrived in body bags; just hours earlier they had been alive, before their plane crashed.

At the hospital, Kelley was among those assigned to X-ray the passengers, to make sure they hadn't died from other causes aboard the military aircraft. It was the military way - the only way she had ever known.

Kelley's mother had been a Women's Air Force officer until the early '60s. Her father, who passed away in February, had been a B-52 bomber pilot in Vietnam and continued to serve in the Air Force, retiring after 27 years.

She had grown up mostly at Wright Air Force Base in Ohio. When she joined the Air Force, 31 years ago, her dad swore her in, she said.

"It was probably because of my military background that I got the job I have today."

She's had it for five years, helping dispatch the right people to a disaster scene, as she and her colleagues did after the tornado strike last year in April when they deployed a mobile hospital to Louisville. The center trains National Guardsmen in bio disaster response. It provides training for paramedics, and much more.

Part of a core group of about 11 people, "I do better when I work for a team," she said. "I know how to follow orders." All these things she absorbed in the military - "where you're always on call for the job." Just as she was that night three decades ago, when the bodies arrived.

It was in San Antonio, Texas, at the medical treatment facility for Lackland Air Force Base.

"We had to X-ray them inside the body bags. We made a factory line.

"How do you stay sane and normal doing something like that? You have to check out for a while. You deal with it later.

"That night was horrific, but it had to be done. I gauge everything else I have to do today against that: 'Well, this certainly isn't as bad as that night.'"

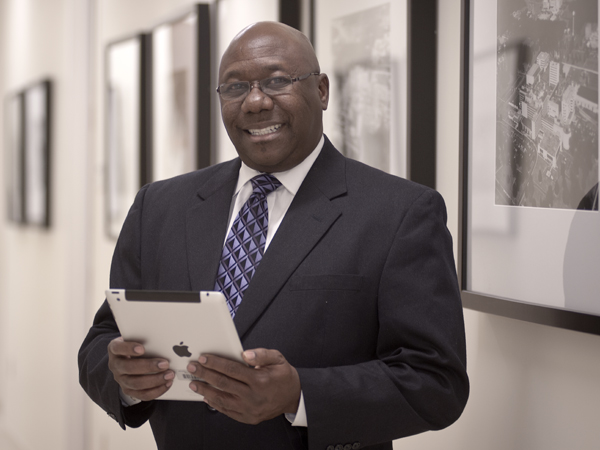

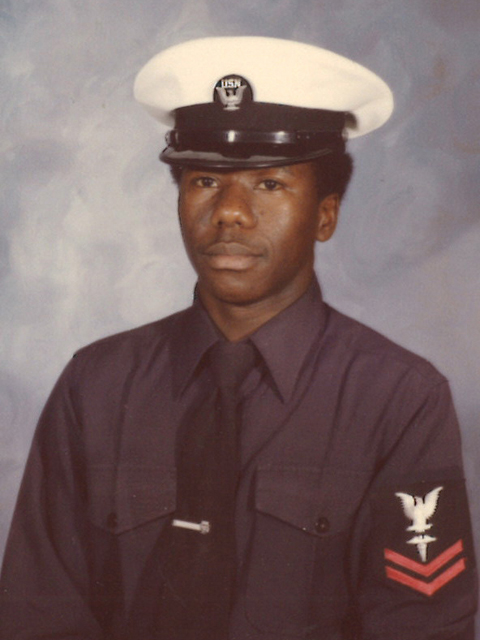

Dr. Claude Brunson

Senior advisor to the vice chancellor for external affairs

Petty officer second class (E-5), hospital corpsman, U.S. Navy, retired

He hated the woods ever since he was a Boy Scout. But now, as a Navy recruit, he was marching and sleeping in the rain-churned muck of Camp Lejeune.

A day or two in, he and his fellow trainees halted at a water-logged ravine. His instructor said, "'The enemy is behind you, what are you going to do?'"

Brunson, around 19 at the time, was a corpsman, meaning he had to march with medical equipment along with regular combat gear. Exhausted, he answered: "I guess I'm going to be captured."

That was right before he felt a booted foot shove him into the water; he wondered if he had made a mistake.

He had joined the Navy while enrolled at Auburn University, where his grades suffered.

"I wanted to be a physician," said Brunson, who had excelled in high school, "but I knew my grades at Auburn wouldn't allow that. I needed a way to re-set."

As a boy, he had wanted to be a doctor at least since the day he fell off his bike, tumbling down a graveled hill that shredded his back. His grandmother, the only "doctor" in their segregated neighborhood, healed his wounds with bandages and salve.

"I was fascinated by the cocktails she made for sick people," Brunson said. "I wanted to be like her."

So, when a Navy recruiter visited Auburn, Brunson signed up as a corpsman, picturing a woods-free life at sea. Instead, the Alabama native was assigned to the U.S. Marines' Fleet Marine Force; that meant a mini-boot camp in the North Carolina countryside.

It meant picking himself up out of a hole in the ground and soaking up a ton of water, along with a lesson he would never forget: Always take care of your buddies. Never turn back.

"Before I went in, I had an entry-level job I loved. Signing up for the military was a dramatic way for me to get away from that and re-focus," he said. "To decide if medicine is what I really wanted to do."

Of course, it was. And, after his Navy stint, the time-honored stresses and anxieties of medical school weren't as hard to bear, he said.

"I learned a lot in the military: sutures, how to make splints out of anything on the battlefield - even a Marine's rifle.

"Even when they're not in combat, military people have accidents. There weren't many things I hadn't seen before."

Dr. Frazier Williams

Oral-maxillofacial surgery resident

Lieutenant (O-3), U.S. Navy, inactive reserves

He had always honored the uniform, remembering to thank those who wore it, just as his mom had taught him to do.

One day, he decided to try one on.

Many in his family had also served, but none had done what he would do.

He joined the Navy after his first year of dental school. "It just felt right," he said. "It was a way to do my part."

His part was a role with the 2nd Marine Expeditionary Force in North Carolina, where he was stationed. He deployed with the Marines to Afghanistan.

"Seeing the sacrifices those young guys were willing to make that far from home," Williams said, "makes you want to do your absolute best for them."

In the Navy, he worked with an oral-maxillofacial surgeon. He helped repair the damage war had done - to faces and teeth. That was the turning point.

Three years ago, he started his six-year residency at UMMC, where he had completed dental school. In three more years, he'll finish training: Dr. James Frazier Williams, oral-maxillofacial surgeon.

"After being in the military, you look at things a lot differently," he said. "It changes everything about you. Even the small things." And the big ones.

Associate professor of pediatrics

Captain, assistant professor of pediatrics, U.S. Army, Army Reserves, inactive

At William Beaumont Army Medical Center in El Paso, the patients she treated didn't wear a uniform. But their parents did.

"I remember a boy who was diagnosed with leukemia," Galarza said. "His father, a soldier, needed time off to deal with this." He got it.

If anyone in a soldier's family needed specialized medical care, the Army wouldn't reassign them to a place that didn't have it.

"This is not how medicine operates in the civilian world," she said.

She entered the military world about 25 years ago after moving to Texas with Dr. Ray Rodriguez. Now a pediatric allergist at the Medical Center, Rodriguez was an Army major at the time. He was, and still is, her husband.

But she didn't join the Army because he had. She joined so she could begin practicing medicine in Texas right away. In the military, you practice wherever you're sent; you don't have to wait for a state license, she said.

At Beaumont, on certain cases, such as child abuse, people worked together as a team - internists, psychiatrists, social workers. "Whatever was needed."

Today, in her practice, Galarza uses that model, putting together teams when needed. "Or if a family has a child who needs a speech therapist, for instance, I try to find the best way to provide one.

"I also see very young mothers who love their babies like they're toys. They don't see that their child is going to grow. Babies are covered by health insurance, but often their parents aren't. Some may have diabetes but can't afford the medication.

"So you advise them - 'who will take care of your baby if something happens to you?'

"Not that they always listen to you. But you plant a seed that may grow later."

Just as the Army had planted a seed in her mind, one that grew and thrives.

"As primary physicians, we can't take care of just the disease the patients have, because whatever they have affects everyone around them." This is the lesson she learned in the military.

"You don't take care of just the patients; you take care of families."

Jonathan Princiotta

R.N., pediatric critical care transport

Captain, flight nurse, Mississippi Air National Guard, active

Most of the soldiers he cares for haven't seen their families in a while. Most haven't tasted a home-cooked in ages. All are ill from injury or disease.

"Our main mission is to provide these patients with the same level of care they would receive if they were in a hospital," Princiotta said, "but we do it at 38,000 feet."

The crew does this on a "flying hospital," an outfitted C-17 that moves the injured soldiers out of Afghanistan to Germany. It takes them to an American-run hospital to complete their treatment or recovery. Or it flies them from Germany for recovery in the United States.

Most of these soldiers are accustomed to the MRE, Meals Ready to Eat; this is the opposite of home-cooking.

"We serve them hot meals on every flight," Princiotta said. "Any kind of warm food, they love it. Hot dogs - they'd eat three or four of them. They were all over it."

During the holidays, they're served turkey from ovens on the plane.

Princiotta has worked as a nurse at UMMC for eight years, transporting children and babies. When he joined the Guard three years ago, he was looking for something new; he found it, he said.

"It is an honor to be able to help those who have sacrificed so much."

He enjoys giving them a taste of home.