Non-invasive procedure averts open heart surgery for mitral valve issue

When you’re constantly tired and out of breath, it’s hard to keep up with a 5-year-old daughter who loves to play Barbies and kick up her heels in the park.

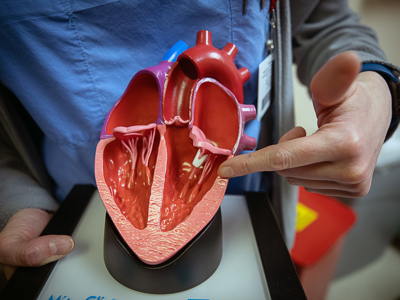

That was the daily existence of Carthage resident Lucious Thomas, a U.S. Department of Agriculture food inspector who coped with a severe heart ailment called mitral valve regurgitation. It occurs when the heart’s mitral valve, located between the upper and lower left heart chamber, doesn’t close as tightly as it should in order to keep blood moving in the right direction.

The valve’s malfunction allows blood to flow backward into the left atrium and travel to the lungs. If left untreated, it can result in heart failure.

“I was very, very run down,” said Thomas, 63. “I could walk through Walmart, but it would leave me exhausted.”

“He was weak and couldn’t even walk to the mailbox, or take the trash out,” said his wife, Tammy Thomas.

That and Lucious’ demanding job left Tammy with much of the caregiving for Ivyanna Thomas, the granddaughter that they’re raising as their daughter. Ivyanna’s mom, Courtney Cooke, died at age 27. Ivyanna was 14 months old.

“Our daughter was murdered on July 2, 2014. Her coworker took her life,” Tammy Thomas said. Christopher Lemon, 37, was sentenced in federal court to 40 years in prison for shooting Cooke five times and leaving her in the back seat of her vehicle on the Natchez Trace near Carthage.

“We are mama and daddy now,” Tammy said.

Ivyanna is the light of their lives, and a big reason why Lucious was determined to get his health back. Even then, he’s on kidney dialysis after suffering a heart attack several years ago and taking medications to deal with that issue. He has but one kidney; Lucious donated the other to his brother 30 years ago.

His caregivers at the University of Mississippi Medical Center recommended he undergo a procedure in which a small metal clip about the size of a large staple is attached to the abnormal part of the mitral valve to make it close more tightly. The clip stays there permanently, allowing the valve to function correctly and to prevent or minimize the regurgitation of blood back into the left atrium and the lungs, said Dr. Kellan Ashley, associate professor of cardiology, who performs the Medical Center’s mitral valve clip procedures.

Patients are given general anesthesia, and a catheter is inserted into a large vein in the groin, Ashley said. X-ray imaging is used to guide the catheter with the clip on its end. The clip is positioned and attached to the portion of the valve where the leak is most severe.

Because of his other health issues, Lucious was a poor candidate for open heart surgery to repair the valve. “To do this procedure through my groin was an easy decision for me,” Lucious said.

On Jan. 31, he became the Medical Center’s first patient to undergo the procedure. It uses a device marketed under the name MitraClip that was first implanted in a Venezuelan patient in 2003. The second procedure at UMMC, that same day, was on Kilmichael resident Julia Ann Flowers, a 75-year-old cancer survivor.

UMMC is one of three facilities in the state and the only one in central Mississippi that offer the mitral valve clip procedure.

For many years, open heart surgery was the only option. For patients like Flowers and Thomas, “it’s too high a risk,” Ashley said. Open heart surgery patients typically spend at least a week in the hospital; those undergoing the mitral clip procedure generally go home the next day.

“This device meets the needs for this patient population,” she said. And although all procedures carry risks, she said, mitral clip patients “don’t have to heal from their sternum being cut open. They don’t have the same risks in terms of having to be on a bypass pump during a surgery.

“They get general anesthesia, but it’s a whole different ballgame, and they’re asleep for a much shorter duration. It’s not nearly as tough on them.”

Patients feel better almost immediately because the amount of blood flowing the wrong way is stopped or greatly decreased, lowering pressure caused in the lungs, Ashley said. “They are back to getting out and about without stopping to rest,” she said of her first five patients receiving the device. A sixth procedure was scheduled for March 13.

Ashley, an interventional cardiologist, received specialized training to perform the procedure, both from the device’s maker and during her fellowship at the Cleveland Clinic. She’s the only cardiologist at the Medical Center doing it, but as patient referrals escalate, more cardiologists could join her ranks.

The procedure was a game-changer for Lucious, who is a candidate for a kidney transplant. “I feel much better than I used to. I don’t get as tired,” he said. “I had the procedure on a Thursday and went back to work on Monday. At times before, I’d have to call in sometimes. I couldn’t go.”

“That first week after his surgery, he went outside and washed both vehicles,” Tammy said. “He hadn’t been able to do that in such a long time.”

Flowers said her leaking valve kept her from playing with her seven grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren. “I was getting real tired, and I was breathing hard,” she said. “I couldn’t stay in the kitchen to cook.”

Today, “I can sweep and clean my house on my own, and I can take my walks again,” Flowers said. “I’m so proud of them down there at UMMC.”