Students self-prescribe healing language in Spanish, French

Published in News Stories on March 09, 2017

Patients sometimes have no idea what health care professionals are talking about (“Edema”? Is that a Disney princess or a disease?)

But when those professionals literally don't speak the patients' language, the communication gap can become a chasm.

In that vein, dozens of dental and medical students here have their ojos wide open. Or their yeux.

They meet in student interest groups to absorb medical terms and phrases in Spanish or French - languages that could prove helpful in their clinics and/or during humanitarian mission trips abroad.

“Even if you're familiar with each other's language, the medical environment is a whole new ball game,” said Dr. Jerry Clark, chief student affairs officer, associate dean for student affairs in the School of Medicine, and faculty advisor to Medical Spanish (Club de Espanol).

Besides Medical Spanish, there are at least two other similar student-led organizations at the Medical Center: the Hispanic Student Dental Association (HSDA) and FrancoMed, the Medical French Student Group.

During their gatherings, the students enjoy digesting the fine points of other cultures - not least of all their food. But there is a more practical reason for future dentists and physicians to familiarize themselves with other tongues, medically speaking.

By the year 2021, around 50 percent of newly-insured patients in this country will be minorities and less likely to speak English - a projection reported in 2015 by the Division of Health Care Improvement in The Joint Commission, the national health care accrediting body.

In Mississippi, more than three percent of the population is Hispanic, which amounts to more than 90,000 residents, based on the most recent population estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau. Of the most common languages spoken in the state, Spanish is second only to English.

“A knowledge of Spanish is pretty handy right here in Mississippi and certainly on this campus,” Clark said.

Bearing that out is Leslye Bastos Ortega, manager of the Office of Patient Affairs' Language Services & Patient Advocacy: In 2016 alone, the number of Spanish-speaking inpatients and outpatients documented at the Medical Center exceeded 16,000, she said.

Beyond offering Language Line - a phone line interpreting service for more than 200 languages - Patient Affairs makes available live, credentialed interpreters for Spanish-speaking patients. At least a couple of the student interest group members have passed the language proficiency exam, including Eric Johnson, a third-year dental student and current president of the HSDA.

Eric Johnson oversees a round of Spanish Bingo during a meeting of the Hispanic Student Dental Association.

For two years, after high school, Johnson lived in Ecuador as a missionary for his church, picking up Spanish, along with some converts.

As a dental student, he has met, and been thanked by, Hispanic patients. “They tell me how nice it is to have a provider who speaks their language,” he said.

In late February, Johnson presided over a meeting of nearly two dozen HSDA members, who competed for gift cards and such in a game of Spanish Bingo, where images, not numbers, are matched on the playing cards. Definitely something the students could sink their dientes into.

As a dentist, it also doesn't hurt to know the Spanish word for “pain,” said Mary Catherine Reynolds, a second-year student who began learning the language as a ninth-grader in Hattiesburg. Useful as well, she said, are the words or phrases for “toothache,” “bathroom,” and “how are you feeling?”

Reynolds has already been on church-sponsored humanitarian missions to Spanish-speaking countries and looks forward to more.

She has maintained, by various means, including through the HSDA, her Spanish skills, she said, but, for the benefit of students as well as their future patients, “I would like to see online Spanish courses integrated into the association, possibly even for dental school credit.”

Actually, there was a time, in the School of Medicine, when a medical Spanish course was available in the Department of Family Medicine, said Dr. Thais Tonore, professor of family medicine and the department's associate director of student programs.

“But we lost our grant,” she said. “We had no resources to continue, but the students went ahead on their own. They're pretty much self-motivated.

“Many just want to reach to those who can't get health care; that's demonstrated through their work at the Jackson Free Clinic,” she said, “and we have a lot of Spanish-speaking patients there.”

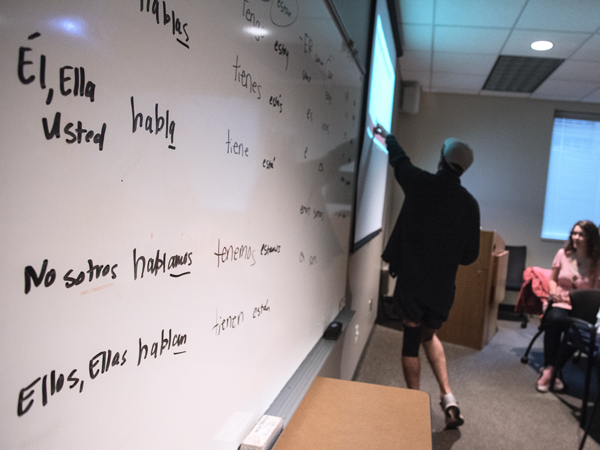

During a meeting of Medical Spanish (Club de Espanol) co-president R.J. Case, portraying a patient, describes his "symptoms," as Mary Ball Markow lists them on the white board.

One of the medical students who serves as a Spanish interpreter is Ronnie “R.J.” Case, a former emergency medical technician in Oxford and the only Emergency Department employee he knew of who could speak fluent Spanish in that hospital.

“Even being able to greet the family of a patient or know something of their culture helps make a connection,” he said. “You don't have to be fluent to be helpful.”

On Feb. 14 - El dia de San Valentin - during a meeting of the Medical Spanish club, Case posed as a patient, describing his “symptoms,” including “dolor agudo” in “el pecho” to other student members.

In the end, first-year student Caleb White deduced “pulmonary embolism.” Exacto.

Two weeks later, on Mardi Gras, members of FrancoMed gathered over King Cake and a Power Point session about the holiday produced by fourth-year medical student Haley Shepherd.

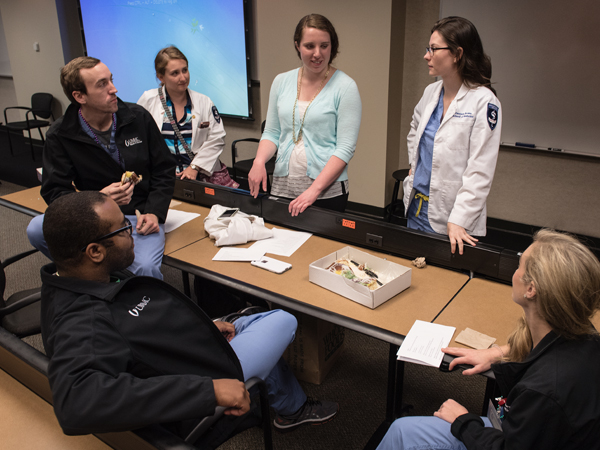

Members of FrancoMed recently met to celebrate Mardi Gras. Clockwise, from bottom left are Jerrell Sims (seated), Colton Lee, Sorsha Morris, Haley Shepherd, Danielle Brown and Laurel Lackey

It's true that, at the Medical Center, you're more likely to encounter a patient from south of the border rather than from the south of France. There were 17 patient-related requests for assistance with French on the Language Line in 2016, and two more for Creole, which is French-based and spoken in Haiti. There were more than 8,200 requests for Spanish.

If those numbers don't compare well, the enthusiasm for the respective languages does. Fourth-year student Jerrell Sims, for one, has “liked the sound of French,” since he was a boy growing up in Natchez.

“Later, I learned that the French culture has a history of being accepting to Africans and African Americans,” said Sims, FrancoMed's outgoing president. “Many, including entertainer Josephine Baker, emigrated there during America's more segregated past.

“And I like languages in general; knowing different languages connects human beings around the world.”

Many of FrancoMed's members, including Shepherd and Colton Lee, who are drawn to the issues of global health, note that French is spoken in many countries [two dozen in Africa alone.]

Lee hopes to someday work with Doctors Without Borders, the international organization known for its humanitarian aid in war-torn areas.

FrancoMed member Laurel Lackey, left, describes how she used her knowledge of French during a medical emergency in Paris, as Colton Lee listens in.

And, like many of the students, including the Spanish speakers, Laurel Lackey has already found her second language useful for helping a patient - including one in Paris who happened to be her best friend.

“She got sick when we were over there together,” said Lackey, a fourth-year student, “so I took her to the nearest hospital.” In a strange setting, far from home, she was able to interpret for her friend.

For her part, Tonore has depended on her Spanish-speaking students or residents to interpret for her on church mission trips to Honduras.

“I just pantomime,” she said. “I can say 'open your mouth' and 'take deep breaths.' I can ask how old they are, if they have a fever. But I haven't been able to have a conversation.

“Still, they all smile the same. You can tell when someone's happy and appreciative, and that we can share without words.”