Dermatology residents 'knock out' plans for patient harm prevention

Dr. Stephanie Jacks remembers the day when a medication error could have meant illness or even death for a tiny patient with hemangiomas, or reddish growths on the skin known as “strawberry marks.”

“I treat a lot of babies with hemangiomas with a medication called Propranolol, and it is usually used as a heart medication,” she said. “People started using it for hemangiomas, but because it's a heart medication, it can affect blood pressure and heart rate.”

A nurse drew up the medication and was about to give the patient the wrong oral dose. “We caught it in time, but it was an eye-opening moment,” said Jacks, clinical director of pediatric dermatology and assistant professor of pediatrics and dermatology.

“We thought, 'We should be checking this every time.' ”

Making a mental note isn't enough when it comes to preventing patient harm. Instead, Department of Dermatology chair Dr. Robert Brodell and his faculty are partnering with their dermatology residents to be a part of the solution.

For the last three years, residents have formulated and put into action their own quality assessment and quality improvement plans to address problems ranging from hand hygiene to dangerous drug interactions. They hold themselves and the dermatology team accountable for adhering to them.

“We knew we needed to do something. We had issues affecting patient safety,” said Brodell, professor of dermatology. “But we were trying to take care of patients, to teach, and to involve ourselves in research efforts. We just didn't have the bandwidth to attack some of the problems.

“But then it occurred to me that we could put our residents at the center of quality assessment. They have energy and new ideas,” Brodell said.

The department's first two residents, Dr. Kenneth Saul and Dr. Kathleen Casamiquela, used as their model the Clinical Learning Environment Review, a program focused on preventing harm to patients. Known as CLER, it's designed to assess the learning environment in residencies and fellowships reviewed by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

“This is an accreditation requirement nationally,” said Dr. Shirley Schlessinger, professor of medicine and associate dean for graduate medical education. “All of our programs must have ongoing quality improvement projects, and all of our residents, before they finish training, must be involved.

“But the dermatology program has taken this a step further,” she said. “Dermatology has really taken the position, and most of our programs are moving in that direction, that quality improvement programs need to be about making a difference for the patient.”

Brodell, Saul and Casamiquela joined Dr. Jeremy Jackson, assistant professor of dermatology, and Dr. Nancye McCowan, professor of dermatology and director of the dermatology residency program, in authoring a manuscript on the effort that was published in the February issue of Cutis, a peer-reviewed clinical journal for dermatologists, allergists and general practitioners.

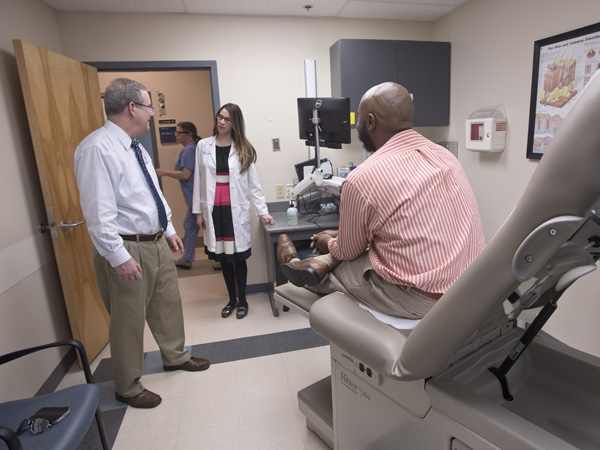

For three years, the dermatology residents - now up to seven - have taken turns sharing their ideas at the department's monthly faculty meeting. “They bounce them off various faculty, determine what the problem is, and try to close the loop with a solution that is practical,” Brodell said.

“Their eyes are new eyes in the clinic,” McCowan said. “We do some things without even thinking, and they'll say, 'Hey, we see it another way.' They look at things and try to make it better.”

Residents tackle patient harm problems without fear of pushback. “All the faculty agreed that we can't have a faculty member saying to a resident or student, 'Quit doing that. Don't you know who I am?' ” Brodell said. “It's critical that everyone moves in the same direction.”

Said Jackson: “We've invited them to do that, and we want them to do that.”

Casamiquela led the charge to fix the perennial problem of lackluster hand hygiene. “The residents acted as secret shoppers to note how well the attendings were using hand hygiene,” Brodell said. “They embarrassed us by telling us that we only used hand hygiene 42 percent of the time when we came into exam rooms.”

Their solution: the “knock.”

“If you see someone not using hand hygiene, within 20 seconds, you make one knock on the counter or wall. That alerts them that they didn't use hand hygiene,” Brodell said. “We went from 42 percent compliance to 80 percent after six months, and 90 percent after a year.”

“Now I do it 99 percent of the time,” Casamiquela said. “Patients have told me, 'I really appreciate you doing that.' It starts off our clinic visit on a good foot.

“I found it really cool to present a unique perspective on reducing the chance of infection simply by moving the location of hand hygiene gels and making it more ergonomically correct,” Casamiquela said.

Jackson hasn't gotten the knock. 'It's always been a habit for me,” he said of hand hygiene. “As I knock on the exam room door, I say hello to the patient and I wash my hands with foam.”

“I'm one of those people who washes off the keyboard with alcohol,” McCowan said. “But I was delighted to see them emphasize hand hygiene. That one was fun from the very beginning.”

The ramped-up hand hygiene “has changed the culture in the clinic,” Jacks said. “We're all on the lookout and trying to catch each other. This makes it so that it's not personal, or a confrontation.”

Saul addressed frequent false warnings of drug interactions that pop up in the Medical Center's Epic computer system. The warnings might be correct - but often, they are due to old information or the physician's methods of administering a drug.

“The residents found that 92 percent of the time when a warning came up on a drug interaction, it was a false alarm,” Brodell said. “They presented data that showed that if there are more than 50 percent false alarms, doctors blow through alarms and risk missing important warnings. We went into Epic and found warnings that someone had gotten a double dose of medicine, when in fact patients are often treated with both.”

Saul asked faculty and residents to identify the individual false warnings they were getting, then worked with DIS to remove each of them from the system. Just one example: Every time ketoconazole cream was prescribed along with ketoconazole shampoo, a common dermatology practice, Epic falsely warned that it was a duplication.

The 92 percent false warning rate is down to 55 percent.“It's a safety mechanism. We want to make sure no patient harm is being done,” Saul said. “And trying to find ways to suppress the unnecessary warnings can actually improve workflow.”

The residents' initiatives “help us keep our eye out for small areas of improvement,” Jacks said. “Not everything is a huge dramatic project.”

Saul offers a specific and memorable example.

“A patient had gum in his mouth when we were doing a toenail procedure, and he passed out and almost choked on the gum,” Saul said. “You don't ever think of asking someone if they have gum in their mouth. So, we needed a 'time out' in place to ask the patient if they have gum or candy in their mouth.”

That question can be raised, Brodell said, when a provider is asking patients if they're allergic to Novocaine, or when a provider is labeling specimen bottles.

While many would fear disclosing weaknesses to an accrediting body, “CLER didn't want to make this part of the normal accrediting. They didn't want people to be afraid to say that they were only at 42 percent compliance on hand hygiene,” Brodell said.

“The spirit of the accreditation requirement is that residents would actually develop leadership skills. That's what dermatology is doing with its residents,” Schlessinger said. “They will be able to head quality improvement efforts in the workplace.”

Saul said he's learned that physicians shouldn't be “set in their ways about things done in the past that aren't efficient. It's easy to go into a situation and say, 'This is how we've always done it.' ”

Brodell gives a special nod to Casamiquela and Saul, who enter private practice this spring after their three-year residencies conclude.

“If those first two residents had said 'we're not going to do that,' and 'it doesn't make sense to me,' there would have been a lot of ways that they could have sabotaged this,” Brodell said. “They embraced this.”