Historic Seven-Way Kidney Swap: A New Year, A New Start

A series of kidney transplants at the University of Mississippi Medical Center could be described as the work of a higher power, a twist of fate or a lucky chance from the perspectives of all involved but no matter the point of view, it’s undeniable that 14 lives were changed over the course of four days.

This incredible story of hope began with one person.

Jennifer McCaffrey’s desire to help a friend in need became an act of altruism that catalyzed the historic 7-way swap. When she found out that her friend needed a kidney transplant, McCaffrey of Raymond volunteered to be her donor. While she was a match for the recipient, she had to undergo additional screening to ensure her kidney was viable for operation. During that time, her friend was matched to another donor—but McCaffrey remained dedicated to donating.

“When they determined me to be an eligible donor, I felt like that was God’s plan all along,” McCaffrey said. “I was led down this path and if I could give my kidney to someone who needs it, that’s what I was going to do.”

It was because of McCaffrey’s selfless decision that this miraculous series of transplants was made possible.

“Living donors—they're my heroes,” said Dr. Christopher Anderson, James D. Hardy professor and chair of the Department of Surgery. “It’s a very selfless act. It’s a gift that I can’t imagine comparing to any other gift. What I have realized over my career is that a motivated live donor is a force to be reckoned with. They will modify their lifestyle, travel long distances if they need to.”

Charting new territory

This expansive internal donor swap stands as one of the largest coordinated by a single center, demanding meticulous planning and coordination. While UMMC executed a two-way internal swap previously, this endeavor involved a more intricate web of logistics.

“It’s resource intensive, but it proves we can do it,” said Anderson. “I’ve been very impressed with not only our transplant team, but all of the teams that help us with transplant—our anesthesia team; our patient placement team, who governs the bed board and flow in and out of the hospital; our nursing teams. We ran an extra OR to get it done. Everyone involved came together to make sure this happened.”

Donor swaps are most commonly done through agencies such as the National Kidney Registry, where participating centers will submit donor and recipient pairs, Anderson said. Occasionally, there will be instances where there are enough mismatched pairs within UMMC that some of them can swap with each other internally.

As the medical director of kidney transplant, Dr. Pradeep Vaitla laid out the plan for the swap, drafting the pairs of compatible donors and recipients, planning all pre-donation testing and work up, assuring that each patient was ready for transplant.

“We have been very intentional and proactive in increasing living donor awareness,” Vaitla said. “We conduct a monthly virtual event to provide living donor education. Our program prompted significant donor interest. However, in this case, not all donors were compatible with their intended recipients. Over the last year, we approved several living donors, but we could not find a matching pair.”

Vaitla said that after continuously searching for approved donor and recipient pairs, the 7-way swap was made possible by a couple of altruistic donors who did not have a family member or friend receiving a kidney in exchange for their donation.

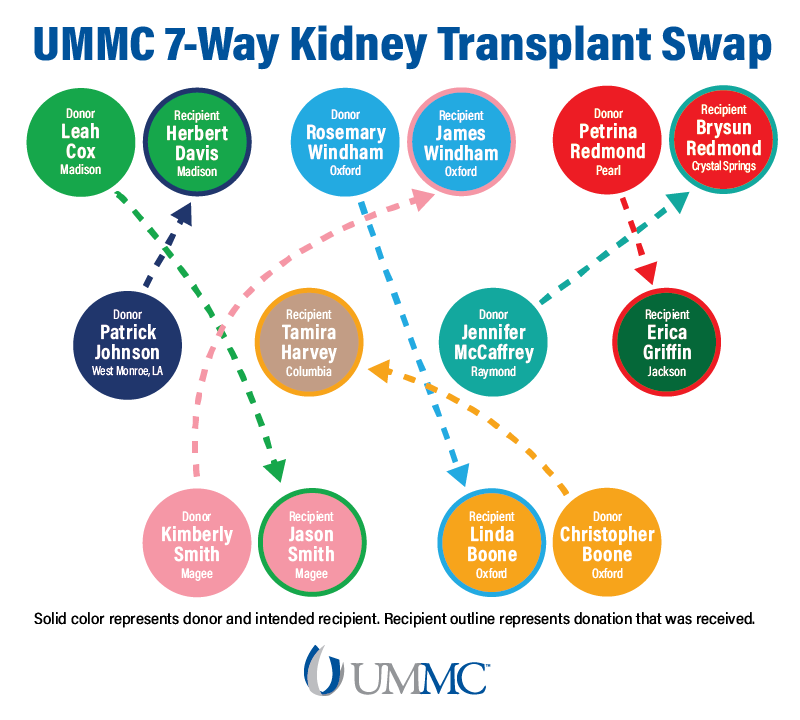

“So the way that it works, for example, is if I need a kidney transplant and I have a willing living donor, but they are incompatible with me for whatever reason that may be, there may be another donor and recipient pair that are also incompatible—but my donor may be compatible with another recipient and their donor may be compatible with me,” explained Anderson.

The largest kidney donor swap in Mississippi was made possible when seven individuals donated their kidneys to seven strangers.

Tackling renal disease

Herbert Davis, head football coach at Madison-Ridgeland Academy, has waited four years to receive a kidney transplant. Suffering from chronic kidney disease for nearly a decade, his health reached a critical point in August 2023 when he was hospitalized for 12 days for an infection that caused fluid to collect around his heart.

Known for his competitive drive and love of football, the Patriots coach hasn’t let his health stand in the way of his dedication to his team. During his stay at UMMC, Davis missed the first and only two football games he’s ever missed in his 30 years as a coach. But even while undergoing treatment in the hospital, he couldn’t keep his head out of the game.

“I was calling some of the coaches on the sideline during the first game while they were stopped at half time,” Davis recalled. “They did a great job and that really helped me. And it helped them grow, too. I’m blessed to have good coaches, but it was tough not being there.”

As his health deteriorated, Davis balanced coaching with nightly four-hour home hemodialysis treatments, after returning home late from practice and waking up early the next morning. Thursdays, Davis said, were particularly difficult when the team had practice at 6:30 a.m.

Davis credits his family, especially his supportive wife, his coaching staff, and his faith for sustaining him through some very difficult times.

“My family, my wife... she’s stayed up with me a lot of late nights,” Davis said. “I’ve been blessed by the Lord to be able to have energy to continue coaching and do what I enjoy doing. My coaching staff has also really helped me pull through. I work for some really good friends who are good, Christian people and they’ve understood what I needed in order to be successful.”

Davis said it was during those two weeks in the hospital that his story really began circulating on social media. “I think everyone realized, then, how serious it really was,” said Davis. “I really thought I was going to die.”

In his absence, the community championed to raise awareness about living donation—even inviting representatives from UMMC Transplant to set up an information booth at football games. The news about the beloved football coach travelled fast, leading to several individuals putting their names forward to donate a kidney.

“I think a lot of people put their name in to be a donor,” said Davis. “But it turned out that my match was right here in my own school.”

It was Leah Cox, the mother of one of Davis’ players, who turned out to be the missing piece in this extraordinary puzzle.

Close-knit strangers

“We only joined the MRA family in August 2021, but it feels like everything has aligned like this for a reason,” Leah Cox said.

She and her husband, Jason, have three sons at the school—Jonas, Fletcher and Asher. Cox said it was her middle son, Fletcher, who first pushed to attend MRA. Fletcher, who is now in tenth grade, has played football since his eighth grade year on the junior high team, but this was his first year playing for Coach Davis. His mom admits that even though she had seen the coach around, she had never had more than one conversation with him prior to this fall.

Cox said that she was unaware of the severity of Davis’ health problems when they got to MRA. “Someone told me when we were attending our first varsity football game after becoming Patriots that he was in need of a kidney and I just have had this feeling in my gut ever since.,” she said. “It has always been in the back of my mind. He was doing well but you don’t realize how much work he had to do to be at the level of health that he was during that time.”

When Davis was hospitalized in August, the administrative staff at MRA informed the MRA families of the severity of the situation and asked for prayer for Coach Davis. The Cox family had recently read an article from Mississippi Scoreboard about one of their staff members' lives being saved by organ donation over 10 years ago. Cox said that after reading of the status of Coach Davis’ health, and reading the Mississippi Scoreboard article, she and her husband thought “why not us?”

Because her husband works full time in his dentist practice, Cox said she had better availability of the two to go through the screening process. After getting in touch with Davis’ family, she was put in touch with Nikki Little, the living transplant coordinator at UMMC—who guided her through the process. Cox revealed that she had only come into the hospital a couple of times before she received a call saying that she was a match to the coach.

In the months leading up to that moment, Cox said that she was never afraid. “I just felt complete peace,” she said. “I have a motto in life: follow the peace. So I was excited to get that phone call. I just went forward with it and trusted the process,” Cox said. “My husband and I are Spirit people, and we choose to follow His leading.”

Although she was a match for Davis, there was a larger plan coming together for the UMMC Transplant team. During a follow-up appointment, Cox found out that she had an additional recipient match.

“Dr. Vaitla told me there was a very large puzzle, but it was missing a piece,” Cox said. “He said I was the missing puzzle piece of a large donor swap. If I chose to donate my kidney to the other match, all these people will also be able to receive a kidney. I was at a college tour with my oldest son, Jonas, earlier that day and I just kept praying that if this wasn’t my plan, to let me know—but I just kept getting signs that this was the plan all along.”

As a mom of three and designated holiday host for the family, Cox wanted to make a few phone calls before committing to moving forward. Her family, she said, was nothing but supportive.

“There was no question about it. It was the most peaceful decision I’ve ever had to make in my life,” she said. “It shifted from ‘OMG we’re going forward with this’ to just being honored to have even been one part of it.”

“I think she really got a calling to try to help me get a kidney—even if it wasn’t going to be hers,” Davis said. “She’s kind of like an angel on Earth. She’s an unbelievable person.”

Cox states that the bow on top of the entire journey was when she found out who her surgeon was. Her car tag references Psalm 104:33 “I will sing praise to my God all the days of my life. I will sing praise to the Lord as long as I have breath.” Leah’s surgeon was Dr. Praise Matemavi, assistant professor of transplant surgery.

Instead of Davis, Cox’s kidney went to Jason Smith of Magee, who had waited two and a half years to receive a new kidney—since his first kidney transplant 25 years ago.

“I found out about my donor through I guess what you’d call ‘the grapevine’,” Smith said.

The identity of organ donors is kept confidential—although, the donors have the choice to reveal themselves to recipients. As fate would have it, Smith’s niece, who works at MRA, is friends with Cox. After hearing that Cox would be donating her kidney on the same day her uncle was receiving one, the two worked out that her kidney was likely going to him.

An added confirmation for Cox as she moved toward surgery day was to find out that her recipient was married to a dental school classmate of her husband.

From friends to family

Smith’s wife, Kimberly Smith, donated a kidney on behalf of her husband to James Windham, of Oxford, who, due to a genetic condition, was only born with one kidney.

The kidney has served Windham well, his wife Rosemary said. But he began experiencing some renal issues after developing diabetes. She said his health declined rather quickly and somewhat unexpectedly shortly after that.

“I think a lot of people don’t realize this is happening to them,” she said. “And then it’s at the door.”

On behalf of her husband, Rosemary Windham donated a kidney to Linda Boone of New Augusta.

"It didn’t bother me that it wasn’t going to be him that got my kidney,” Windham said. “God has a plan and I think things fall within God’s plan.”

The kidney transplant was Boone’s second at UMMC, after receiving a liver transplant in 2015.

Boone was able to meet her donor soon after receiving the new kidney. Grateful beyond words and eager to keep in touch, Boone’s husband, Christopher, asked Rosemary Windham to add him as a friend on Facebook. But when she typed in his name, she discovered that they were already friends.

“She works in real estate and he’s a land surveyor,” Boone explained. “Those kind of work hand-in-hand so they crossed paths at some point.”

Life after donation

Procedures on this scale wouldn’t be possible without the benevolence of living donors.

“More than 60% of people with kidney failure needing dialysis do not make it to five years while a living donor transplant increases the survival to greater than 90% at five years,” said Vaitla.

It was because of each of the seven donors, that recipients and their families can begin a new journey.

“I think what a lot of people don’t realize is that kidney transplant lengthens the lives of people with end stage renal disease compared to being on dialysis,” Anderson said. “Every year you're off dialysis with a transplant, you gain a survival benefit.”