Patients benefit from GI testing technology enhancements

Published in News Stories on August 29, 2016

Those who suffer from gastrointestinal disorders - including acid reflux, intestinal bugs, diarrhea, bloating and unexplained bleeding - often find themselves managing those problems without knowing their cause.

But outpatient tests now available at UMMC mean getting to the root of such GI issues can be as simple as breathing into a small plastic bag or swallowing a tiny camera that looks like a pill.

Sones

“They can make a real impact for people with growing gastrointestinal complaints that have been mysterious,” said Dr. James Sones, professor and chief of the Division of Digestive Diseases.

Paxton Phillips, a GI motility specialist, administers the tests that are new to the division's Special Procedures Unit and Adult GI Services.

“Not all of these procedures are totally new, but they've fallen by the wayside because they require a trained technician,” Sones said.

Phillips has more than a decade of experience in performing the procedures and tests. They include:

* Small bowel capsule endoscopy, which examines the middle of a patient's gastrointestinal tract, or small bowel, by tracking the route of food from the time it's swallowed until it reaches the colon. The test, meant for patients whose problems weren't identified despite having an upper and lower endoscopy, involves the patient swallowing a plastic capsule containing a camera.

After being swallowed, the tiny camera is capable of taking thousands of photos of the of the inside of the gastrointestinal tract.

The camera captures up to six images per second as it travels through 20 feet of small intestine - an area that a traditional endoscope can't reach. A camera can take up to 60,000 pictures, and the images are recorded by a small device patients wear on their belts. The test can last between two and eight hours, depending on how long it takes for the capsule to reach the colon, where it's eliminated through the digestive tract.

Those images can help identify the sources of bleeding, chronic weight loss, constipation, diarrhea and conditions such as Crohn's disease, Phillips said.

“Some of the tests come back perfectly normal, so that gives peace of mind that the patient doesn't have a serious problem,” he said.

* High-resolution esophageal manometry with impedance, which measures the length, strength and function of the esophagus and the strength of the muscular valve connecting the esophagus to the stomach, called the lower esophageal sphincter.

That valve prevents food and stomach acid from backing up out of the stomach into the esophagus. If it doesn't work properly, backed-up food and acid can cause gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD.

The procedure is done with a catheter about the size of a flexible, thick spaghetti noodle. After application of a local anesthetic, the catheter is passed gently through one side of the patient's nose. It travels down the throat and into the esophagus.

This catheter is placed into the patient's esophagus through their nose.

The patient drinks several swallows of a sports drink, then swallows of viscous fluids such as gelatin. The swallowing motion is captured as a scan and analyzed to see how well the valve is working. The entire procedure takes about an hour.

“The patient swallows and you measure the strength and pushing force of the esophagus and whether or not the muscles are synchronized to push the food forward,” Sones said. “When you don't have that motility, the food just sits there.

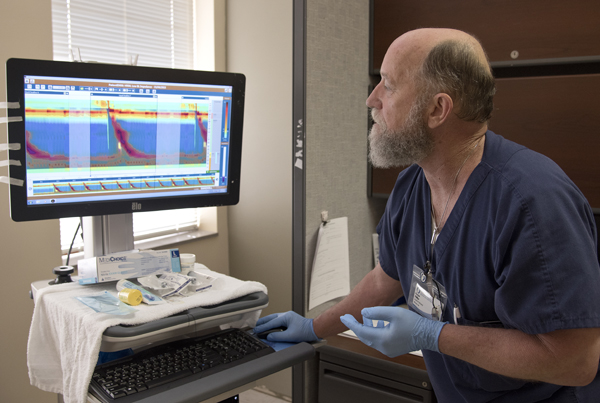

“With the addition of high resolution, we can look at it like you'd look at weather radar,” Phillips said. “Instead of lines like you would see on an EKG, you will see colors that represent pressures.

“With the addition of impedance, which is watching a person swallow, we can see if the swallow clears the esophagus. We can understand the mechanics more in depth.”

Phillips looks at images that show the pressure of a patient's swallowing motions.

* Bravo, a test that measures how much and how often acid from the stomach backs up into the esophagus. The two-day test can be challenging because the patient must stop taking antacid medications for several days so the acid can be measured.

The patient swallows a small microchip equipped with batteries, an antennae and a sensor. The chip attaches itself to the esophagus via tiny suction cups.

“It measures every time acid comes into the esophagus from the stomach and sends a signal to a recorder,” Phillips said. “If the patient feels reflux, they push a button on the recorder so that we can correlate symptoms to the reading at that time.”

Sones said before use of the chip, “when we did a scope, we could see where the esophagus was being burned, but we couldn't tell how much reflux a person was having. That's important, because we need to know if they need surgery or if they need to manage it with medications.”

The tiny chip generally falls off the esophagus in a few days and passes through a patient's digestive tract, Phillips said.

* 24-hour pH test with impedance differs from Bravo in that the patient doesn't have to temporarily halt his antacid medications. The patient wears a small catheter tube placed through his nose that travels down the esophagus. The test measures both acid and non-acid levels of fluids that back up into the esophagus.

* Hydrogen breath test, which identifies bacterial overgrowth in the small bowel caused by bacteria migrating from the colon up into the intestines. When that occurs, a patient can develop problems, such as lactose intolerance, bloating or diarrhea.

The three-hour test is a more patient-friendly alternative to collecting and submitting a stool sample for analysis. The patient breathes into a small blue plastic bag to establish a baseline, then drinks a solution that produces a gas and breathes into the bag again.

Phillips analyzes changes in the patient's breath to determine how high up into the intestines the bacteria has traveled. The test takes about three hours.

Coming soon is a component to the breath test that will show whether H. pylori bacterial infections that live in a person's digestive tract have been eradicated by antibiotics.

Kelly Bullock of Merigold recently traveled two-and-a-half hours from the Mississippi Delta for an 8 a.m. appointment at UMMC in hopes that small bowel capsule endoscopy would explain why she's had a lack of appetite, weight loss, nausea and other unpleasant gastrointestinal symptoms, such as hematophezia, or blood in the stool.

“I couldn't eat, and then things started burning my tongue,” Bullock said. “I can't drink a cherry limeade, and I'm having trouble stomaching food. I can't eat a baked potato.”

Phillips gently placed a cloth belt around her waist that supported a recorder about the size of the palm of his hand. Bullock swallowed with ease the capsule that's also equipped with a sensor to gauge how fast it's traveling through her digestive system.

Phillips places a cloth belt containing a recorder around the waist of Bullock

“The pill and the recorder are going to talk to each other,” Phillips told her.

He instructed Bullock to drink clear liquids two hours after the procedure, then full liquids at four hours, followed by a soft diet, such as macaroni and cheese or pancakes. Bullock was told to return to Phillips' office in early afternoon to see if the capsule had traveled to her colon, signifying the end of the test.

“It's your souvenir,” Phillips joked with Bullock. “We don't want it back.”

What all of the tests have in common, Sones said, is that they go beyond an initial screening.

“They are for patients who have reached the end of their rope for chronic conditions,” he said. “This opens up another whole realm of evaluations.”

Phillips agreed.

“The future of this is unbelievable,” he said. “What you see here has evolved. Even the software for viewing the tests has improved.”