Physiology still matters, says Mayo Clinic’s Joyner

Published in News Stories on November 09, 2015

Will advances in genomics and targeted therapies be the silver bullet to treating and curing human disease? Dr. Michael Joyner thinks we need a second opinion.

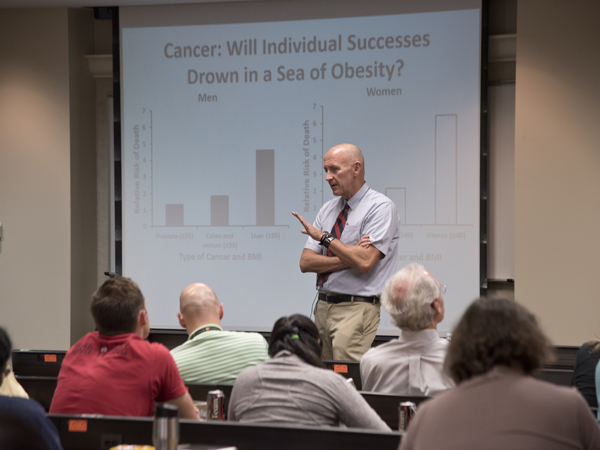

Joyner, a professor of anesthesiology at the Mayo Medical School in Rochester, Minnesota, gave the Physiologists in Training (PIT) Distinguished Research Lecture Nov. 5 in Classroom Wing 308. His talk, “Our Physiological Future,” addressed some of the shortcomings of the genetic revolution and why traditional clinical physiology is still needed to solve research problems.

The PIT distinguished lecture has been happening for several years, said Dr. Carolina Dalmasso, a postdoctoral fellow in physiology at UMMC and a leader of PIT. Trainees select a speaker and organize the event, giving themselves the opportunity to learn from renowned researchers outside of UMMC.

“Dr. Joyner has an excellent history of mentorship, with over 100 mentees during his career, from undergraduates to residents,” said John Henry Dasinger, a fourth-year PhD student in physiology and a student leader in PIT. Joyner also is an accomplished researcher, known for his work in exercise physiology, cardiovascular function and blood transfusion practices. His wide-ranging experience is another reason PIT invited him to give the 2015 lecture.

Joyner, center, receives an honorary plaque from PIT leaders John Henry Dasinger and Dr. Carolina Dalmasso.

According to Joyner, efforts like the Human Genome Project gave some scientists high expectations for the usefulness of genes in predicting disease risk. The premise is that someone's genotype, or DNA, influences his or her phenotype - the appearance and health characteristics. With technological advances, the applications for medicine seem endless. Gene replacement and targeted drug therapies are two common examples.

But in many cases, Joyner said, genes have limited explanatory power. For example, researchers look for cardiovascular disease risk factors in a person's DNA. The screening techniques used take hours to work and lots of money. But the genes linked to these common diseases only explain one or two percent of the population's variability.

What's a better predictor for cardiovascular disease risk? Waist circumference. All it takes is one person, one minute and a one-dollar tape measure, said Joyner

Joyner also noted the lack of major therapies and drugs developed from advanced genomics alone. “Dr. Hall,” he joked with UMMC physiology department chair Dr. John Hall, “you've been [at UMMC] a long time. Where are the cures locked up?”

All joking aside, Joyner acknowledged the value of the genetic revolution, including the development of Gleevec, a drug for chronic myeloid leukemia. He also noted that some treatments originally tested for some diseases turned out to be more effective for other uses, like Viagra. Because of this, he said good old-fashioned physiology remains a critical tool in medical research.

“It is better living through plumbing, electricity and traditional drugs,” said Joyner.

Joyner used an example from his own research. Part of his work involves measuring the heart's ejection fraction - how efficiently the heart pumps blood. Too high or too low can signal heart failure. His lab showed that frequent exercise or use of beta-blocker drugs are better preventive strategies than newer, advanced, genetically-based treatments.

Joyner was well prepared for the question and answer period after his talk. He had extra slides in the presentation which anticipated many audience questions.

“I promise these aren't planted questions,” he said. It was another indicator of Dr. Joyner's wide-ranging preparation, expertise and influence on the field of physiology.

If interested, Joyner keeps an active blog where you can read his thoughts on the limits of human performance at http://www.drmichaeljoyner.com/.