Asylum Hill Project: 'What a great story this is'

ASYLUM HILL RESEARCH CONSORTIUM

The University of Mississippi Medical Center

The University of Mississippi

Mississippi State University

Jackson State University

Millsaps College

The University of Southern Mississippi

Texas State University

University of Idaho

Jannie White of Southfield, Michigan, knows this about Speedy Ann Williams: She wore her long, black hair down to her hips and was born near Copiah, and someone brought her to Jackson.

White also knows that her great-grandmother had two sons and died at age 78 on Oct. 19, 1922 of “arteriosclerosis/insanity,” as recorded by the institution where, after a stay of two months and 16 days, she took her last breath: the Mississippi State Insane Hospital.

White knows little else about the life and death of her Mississippi ancestor, but, of the many unanswered questions she entertains about her, this is one of the most important: Where is she?

“To know that she was buried in a particular location would bring some closure to me and my family,” said White, who lives some 950 miles from Speedy Williams’ conceivable resting place: the campus of the University of Mississippi Medical Center, in one of thousands of unmarked graves.

It may not be possible, at least for now, to find the exact burial sites of Speedy Williams and the other residents who died and were interred at the institution that shut down and moved more than 80 years ago; but with pending action in the state legislature, an effort to remember their lives may be gaining ground.

That effort is one of the tasks of the Asylum Hill Research Consortium, a band of experts and scholars created by Dr. Ralph Didlake.

Another aim is to relocate, collect and organize the remains found in the anonymous graves, which must be done respectfully and ethically, said Didlake, UMMC professor of surgery, vice chancellor for academic affairs and director of the Center for Bioethics and the Medical Humanities.

“There are more than 10,000 documented deaths at the asylum,” he said, “but we don’t know how many of those patients were buried on site.”

More than 4,300 hospital death certificates are available online through the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Some of the information Jannie White has learned about her great-grandmother is in that database, which covers the period of November 1912 through March 9, 1935.

Some of White’s family members, now deceased, described to her Speedy Williams’s long, black hair; others told her that her great-grandmother had mixed Native American and African American ancestry.

“We can only assume she was part Choctaw,” White said. “Any solid information we can find out about my people would be greatly appreciated by me and the rest of my family.

“My roots are there in Mississippi, and my husband’s roots start there, too.”

NOTHING ELSE LIKE IT

“This project is fascinating,” said Lida Gibson, a Mississippi film documentarian who has been hired to help coordinate the undertaking, write grants for it and document it with interviews and video.

“What a great story this is,” said Gibson, who is also working on a website for descendant families to consult and contribute to; the site may be up by this summer.

“There will be a portal on the website for people to share information, including stories passed down by the families of patients, and by anyone who has memories of the asylum. We are reaching out to them now. I have a feeling that some of the best resources may be people’s personal letters.

“There’s really nothing else like the Asylum Hill Project. It’s so important to honor these lives.”

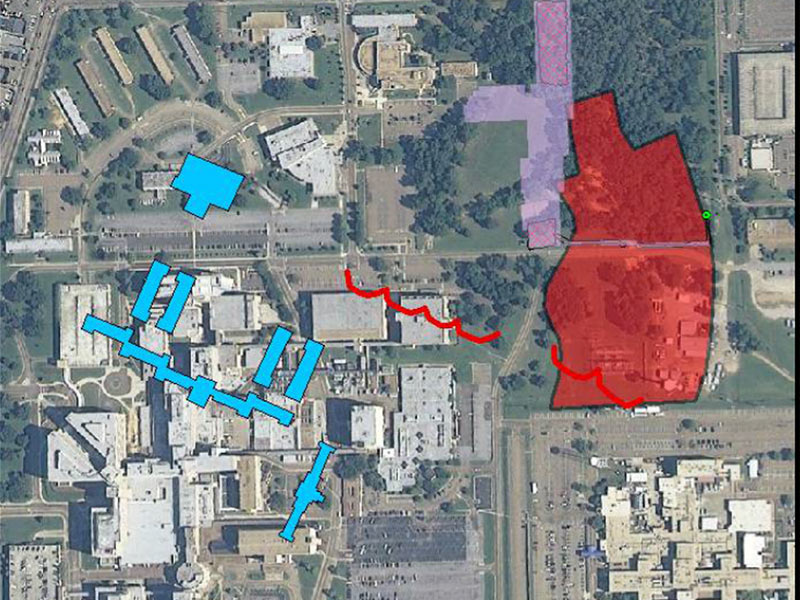

So far, 67 of those lives continue to be examined in death; that’s the number of asylum residents whose coffins were exposed accidentally – all but one by a road construction crew in 2013 on the northeast part of the campus. Later, a geophysical survey showed that many more coffins lie underground and unmarked across some 20 acres of UMMC, which opened in 1955, 20 years after the asylum closed.

Archaeologists are “confident,” Didlake said, that there are 3,000 bodies, but as many as 7,000, on campus. Bills being considered by state lawmakers will expand UMMC’s authority to move them elsewhere on Medical Center property.

Didlake hopes a final bill will be passed this legislative session; it would then require the signature of Gov. Phil Bryant.

The so-called Phase I of the Asylum Hill Consortium’s plan is to place the remains in UMMC’s Farmer’s Market facility, which houses a Rowland Medical Library print collection; it offers temperature and humidity control, a fire suppression system, back-up electrical power, 24-hour key card security and 9,000 square feet of archival space.

This will be, in effect, the new resting place of several thousand people, until a permanent memorial is built.

“We don’t know if we’ll exhume everyone,” Didlake said. “The extent of the cemetery is still unknown.” Construction may have obscured some of the gravesites. “But we will exhume as many as possible.”

The cost of archiving and storing the remains, creating space for scholars to work in, and reclaiming the current burial sites for future land development is around $2.2 million, Didlake said.

“We’re not asking legislators for any money this year,” he said. “We just wanted them to adjust the law.”

Another $3 million or so will be sought for the second part of the consortium’s plan, but the goal is to pay for it, not with state money, but with “external funding,” Didlake said. It calls for creating a memorial to the asylum residents, as well as a field school with a long-term scientific and educational program.

All of these plans may not be realized for another six years or more, Didlake said.

The discovery of the graves is a boon for anthropologists, archaeologists, historians and other experts. It offers them the opportunity to learn more about past disease treatment practices, social history, conditions in the Jim Crow South and much more. Already, graduate students at Mississippi State University have written at least three master’s theses based on information gleaned from the graves.

“Studying them tells us a lot, not only about the asylum, but also about conditions across the state of Mississippi until 1936, when they moved the institution to Whitfield and ultimately established a cemetery there,” said Dr. Nicholas Herrmann, a former associate professor of anthropology at Mississippi State University.

Now an associate professor of anthropology at Texas State University, Herrmann directed the 2013 excavations at the Medical Center when he was at MSU; today, preparing the technical report on the 60-plus burials.

“Just about every county is represented, according to the death certificate information,” Hermann said, referring to the records available on the MDAH website.

Because many families have moved from Mississippi since 1935, interest in these burials extends far beyond the state’s borders.

LIFE, DEATH AND HISTORY

The pine coffins holding the patients were probably built in an asylum workshop. The pine probably grew in the DeSoto National Forest region or the Mississippi Delta, as revealed by Dr. Grant Hartley, a former University of Southern Mississippi assistant professor and a geographer whose research focuses on dendrochronology, the science of dating tree rings.

Likely, the wood was shipped to the asylum by train; a rail spur is depicted on ta 1925 insurance map of the institution, Herrmann said.

Demographic information (race, gender, age, etc.) along with isotope studies – that is, the analysis of chemical elements of a few burials – has enabled Herrmann to narrow the identity of the person in the first, single grave discovered (“Burial 1”) to 20 individuals.

He may be able to narrow that number even more, he said. “Will we ever be able to say certain remains are this specific individual’s? I’m not sure.”

One thing that is certain about the vast majority of the people who died and were ultimately buried at the asylum: their race. Between 1912 and 1935, most who died there were “black,” according to records from the asylum, which began admitting African Americans after the Civil War.

Whatever their race, their lengths of stay varied widely. In Hinds County, for instance, one of the patients was there for more than 47 years. Others “died at birth” and their mother’s name was listed.

No infant-sized coffins were unearthed, Herrmann said.

Many of the patients had pellagra, caused by a deficiency of niacin, part of the Vitamin B complex found in such foods as fish, poultry, red meat, and fortified breads and cereals; it was more common in the early 20th century, especially in the South, where meals were rich in fatback, molasses and cornmeal.

Pellagra could result in, among other conditions, dementia. Available asylum records show that a disused psychiatric diagnosis, dementia praecox, or premature dementia, was often recorded as a cause of death. Other diagnoses listed include “pellagra/insanity,” “melancholia,” “general paralysis of insane,” and “maniacal exhaustion.”

“The records we have can give a good indication of what life was like in a sanatorium,” said Dr. Shamsi Berry, assistant professor of health informatics/information management in UMMC’s School of Health Related Professions.

“They can give us an idea of what conditions are like in similar institutions that exist today in some less developed countries,” said Berry, whose role in the project is, among other things, developing curriculum for the field school.

“The same diseases are being passed down today because of the same level of nutrition and lack of care. From bones we can sometimes determine the presence of certain diseases. It’s important to understand the way we treated disease in the past, which affects the way we treat disease today.

“But, first of all, this is a piece of our history in Mississippi.”

BUTTONS AND SHROUDS

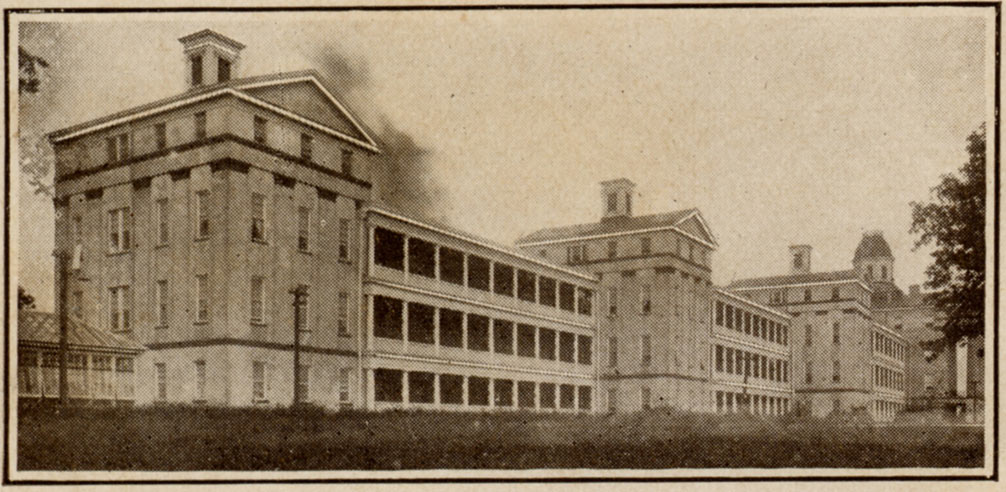

Originally known as the Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum, the institution moved to its present location, the Mississippi State Hospital in Whitfield, after operating from January 1855 to March 1935.

Around 35,000 people were institutionalized during that time, and an estimated 10,000 to 11,000 died on the premises, said Dr. Molly Zuckerman, associate professor in the Department of Anthropology and Middle Eastern Cultures at Mississippi State University.

Zuckerman is now studying the bones and skeletal fragments uncovered during road construction. The people they represent were all buried in the 1920s and 1930s, a finding based on dendrochronology.

The pine coffins that held them contracted and expanded over time with the movement of the shifting clay soil.

Depending on where a burial was recovered, the condition of the bones varies, from relatively well-preserved to highly-fragmented.

“Sometimes, the fragments are so small you can’t identify which bones they came from,” Zuckerman said.

The coffins contained few, if any, personal items that might have helped identify those who lay in them. “People were buried in shirt dresses and shrouds, so shroud pins were found,” Zuckerman said, “as well as a variety of buttons, probably from the shirt dresses.”

Each of those buried had his or her own coffin and each faced the rising sun.

Some grave markers were found, but were no longer in their original positions, Herrmann said. These were placed in the UMMC Cemetery located in the northeastern part of the campus.

“Regarding the patients who were buried, what we see is absolutely consistent with similar institutions in other parts of the United States and Europe,” Zuckerman said.

But, without DNA analysis and descendants providing DNA samples, it’s impossible to match certain remains to a death record, said Berry. “And the cost would be too great.”

In other ways, though, what can be learned from this project is priceless.

IT’S PERSONAL

“The written history of disability in this country is disproportionately about white people,” said Dr. Janice Brockley, associate professor of history and a disability historian at Jackson State University.

“That’s one thing that’s really important about the work of the consortium. The knowledge we can gain can help us understand who was in the asylum, what conditions and therapy they experienced. It can help us learn more about people in Mississippi in general, but especially about the history of African Americans with disabilities.”

Many of the residents were directly descended from slaves or might have been bound at one time in slavery, an institution that wasn’t meticulous about recording the details of its victims’ family histories.

For that reason, getting a handle on personal genealogies can be difficult for people like White. But she’s determined to recover all of her family’s story.

“First of all, I’m a person of color. For someone to tell me that I’m straight from a cotton field without a history, I don’t accept that,” White said.

“Before I leave this world, I want to tell my children, ‘This is who you are and this is where you came from.’”