Hearing never sounded so good for Jackson preteen

Enjoying the newest Euro techno pop mix, a casual conversation or the voice of her mom is all very important to Jocelyn DeZutter, a determined preteen who was born without her ear canals and outer ears.

Her desire to make the most of technology that gives her sound led the sixth-grader to power through the pain caused by a hearing device hooked to a headband she wore non-stop. “Jocelyn liked the volume so much that she was wearing the headband very tightly, and it was causing a major breakdown of the skin on her head,” said Dr. Beth King, an audiologist and assistant professor in the Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Jocelyn needed technology that would reduce her struggle to hear and her risk of injury and infection. She’s among a small handful of Mississippi hearing-impaired children whose world has been changed by a state-of-the-art bone conduction implant positioned just under the scalp. It allows sound to reach Jocelyn’s healthy inner ear through vibrations that travel across bone.

Eleven-year-old Jocelyn was born with bilateral microtia and ear canal atresia. She was living in foster care in China when she was adopted as a 3-year-old by Jackson resident Stacy DeZutter.

“She has a normal inner ear and a normal cochlea. It works fine,” said Dr. Jeff Carron, professor of otolaryngology and a head and neck surgeon. “But because she has no outer ears or ear canals, the sound doesn’t conduct from the outside into the inner ear. The challenge is to get the sound to the inner ear, and to bypass what’s missing.”

On June 5, Jocelyn received a bone conduction implant for her left ear during an hour-long outpatient procedure under general anesthesia. Carron performed the surgery, giving Jocelyn the latest technology for those with her particular hearing loss.

“The surgery was really quick,” DeZutter said of the procedure requiring a two-inch incision. “Jocelyn came home and said, ‘What can I have for lunch?’ The next day, she wanted to be outside.”

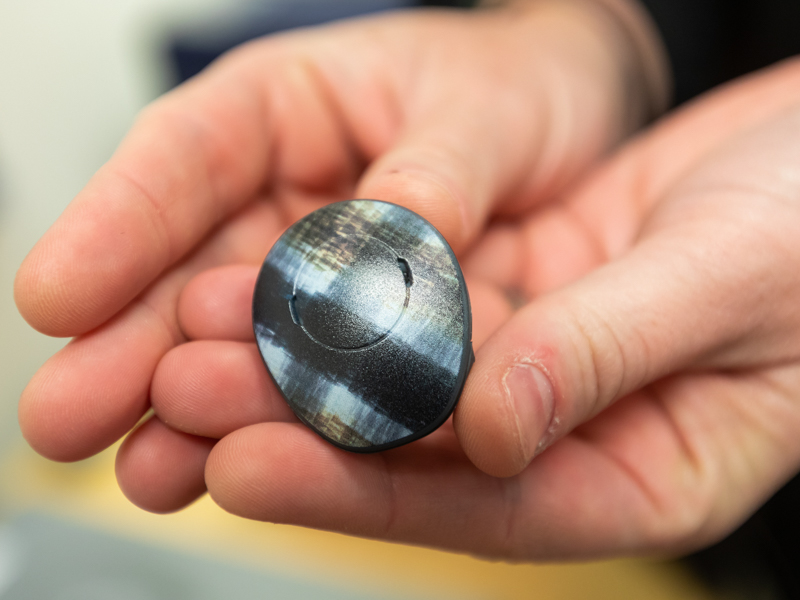

The technology consists of an externally worn audio processor the size of a quarter and an implant. No part of the bone conduction implant protrudes from the skin. The external audio processor lies on top of the implant and connects to it using a magnet.

Microphones on the audio processor pick up sound waves. The processor converts the sounds into electrical signals that are transmitted into the implant. The implant converts those signals into vibrations, and the bone conducts the vibrations to the inner ear.

“The processor takes the sound from the environment and turns it into a digital signal. It overcomes the obstacle of the loss of the ear canal and outer ears,” Carron said.

King activated Jocelyn’s new device on June 24. UMMC, through its pediatric arm, Children’s of Mississippi, is the only hospital in the state offering that technology to children. “There was an immediate difference in her hearing,” King said. “We were able to give her great access to sound.”

“It’s hard for her to articulate it, but I think she gained sensitivity to speech sounds with the new implant,” DeZutter said. “She’d tell you that she likes it because it’s Bluetooth-capable. She can talk on her phone much more easily now.”

When DeZutter began the adoption process, she learned that China allowed single mothers from other countries to adopt, so long as they agree to take a child with medical needs.

DeZutter, an associate professor of education and psychology at Millsaps College, readily agreed. Jocelyn “was living in a village in rural China. She had no correction for her hearing,” DeZutter said. “She was just surviving on grunting and pointing.”

DeZutter immediately began teaching Jocelyn American Sign Language, “but she used her voice so much that it was clear to me that she wanted to be oral.”

She enrolled Jocelyn at Magnolia Speech School in Jackson. “It’s a world-class oral school, and they helped us acquire the technology that we used until June,” DeZutter said. “With that and their intensive language program, she was two years behind her peers in language, but on track with reading.”

“Without devices, a jet engine would be quiet to her,” King said. “Speech would not have developed without amplification.”

DeZutter transitioned Jocelyn to Casey Elementary in the Jackson school district midway through first grade. “Immediately, she is on the honor roll,” DeZutter said. “She worked very hard at her schoolwork, and she is a very outgoing person. That’s good, because she easily gets a lot of her language exposure from other people.”

“I need to hear well, because I need to hear what people are saying,” Jocelyn said.

Jocelyn began a series of surgeries at a Minneapolis children’s hospital to rebuild her outer ears using her own rib cage cartilage. She was initially seen for her hearing loss at UMMC by Dr. Claude Harbarger, assistant professor of otolaryngology.

Over the years, Jocelyn’s headband became more problematic. She’s very active and loves to ride her bike and play tennis. “The technology was old, and it wasn’t serviced anymore,” DeZutter said. “She was getting a lot of infections and sores.”

Jocelyn “was losing a lot of sound, especially high-pitched ones,” Carron said.

The bone conduction implant, Carron said, has been available in the United States for almost two years. “It’s the best tool available for what we call conductive hearing loss, in which a child is born without an ear canal, or someone is born with hearing bones that didn’t form right. A typical hearing aid often isn’t going to work for them.”

So many of Jocelyn’s outside interests are much more enjoyable thanks to her ability to hear: Playing the flute and recorder. Playing video games. Taking part in the Jackson district’s Open Doors gifted education program.

“Jocelyn doesn’t think there is a limit to whatever she can do,” DeZutter said. “She’s never seen herself as disabled. I don’t even use that word around her.”

The day her new device was activated was doubly meaningful for Jocelyn and her mom. “We took advantage of the timing so that we could have an extra-special Gotcha Day,” DeZutter said. “Gotcha Day is what adoptive families call their adoption anniversaries. After she got turned on, we went and had a special mama-daughter meal at our favorite sushi place - carry out, due to COVID!”

Three days after her surgery, Jocelyn got braces. “I miss popcorn,” she said.

Jocelyn, King said, “is remarkable. She is mature beyond her years. We think she would benefit from an implant on the right side, also. But even with just one ear, she is hearing great.”

“I fall in love with her again every single day,” DeZutter said. “She’s an amazing kid.”