First father, then son: Heart transplants give family second chances

From when she was 15 and he was 18, Brad and Becky Fitzgerald have had each other's hearts.

They dated four years before they married. It's been 25 years and two daughters since they said their vows, and Becky Fitzgerald no longer has Brad's heart that she cherished as a teen.

The McComb resident instead has her husband's new heart, a priceless and perfect organ that on March 31 began beating in his 46-year-old chest, thanks to his transplant team at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

They don't know the donor's family, and might not get their wish to thank them personally. “But, they can rest assured that heart will be well taken care of,” Becky said. “We won't do anything to disgrace this gift.”

Brad's father, Nick Fitzgerald, held sacred that same blessing. Nearly 20 years ago, a different set of UMMC surgeons performed a transplant on the elder Fitzgerald after his organ, battered by multiple heart attacks, gave out.

“For these two ... That's extremely rare,” said Dr. Matthew deShazo, Brad's Medical Center cardiologist.

“It boggles my mind,” Brad's only sibling, UMMC registered nurse Jo Hubbard, said a week after Brad's transplant. “How can both a father and a son end up needing a transplant, for two entirely different reasons? We'd already had one miracle. How could God give us two miracles?”

Brad's miracle has been in the making since he broke his neck in 1999 and later developed a viral infection that weakened his heart. Brad's cardiomyopathy, possibly genetically related to his father's heart disease, was confirmed while he was hospitalized for the broken neck. He began seeing Dr. Earl Fyke, a veteran cardiologist at Baptist Hospital in Jackson. The Fitzgeralds, Fyke and Fyke's nurse, Kakie Magann, developed a close relationship as Fyke, for 16 years, kept Brad's heart failure in check.

“He wouldn't be here now if not for Dr. Fyke,” deShazo said.

As time passed, “I could hardly get up and walk through the house,” Brad said. He continued working in an administrative role at the family's fifth-generation water well drilling business, but “it was a daily struggle to get enough energy.”

Two years ago, he and Becky handled another family health challenge. Becky was diagnosed with breast cancer and underwent a double mastectomy. “Our faith plays a huge part. We prayed,” Brad said. “Just because I believed God's got this, it hurts you to know someone you love is going to hurt. But God just got it.”

“Otherwise, he would probably have died of cardiac arrest, maybe on his tractor or bulldozer. This is such incredible technology,” Fyke said. “People like Brad wouldn't be here if not for us being able to put in their own personal paramedic. That has kept Brad from being an obituary from McComb, and gave us the time to get him to UMMC.”

In January 2015, Brad said, Fyke encouraged him to begin a relationship with deShazo and the state's only heart transplant team. “He said, 'Brad, it's time,'” Brad remembered.

“I said, 'I've known you for a long time, doc. Would you trust them?' He said, 'Absolutely.'”

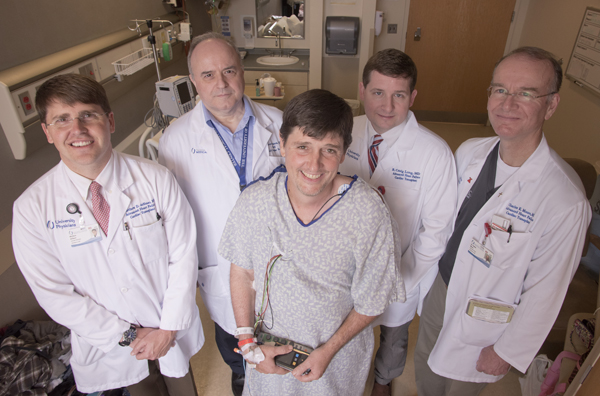

Brad's Medical Center team includes three cardiologists and four surgeons: deShazo and cardiologists Dr. Craig Long and Dr. Charles Moore; and surgeons Dr. Anthony Panos, Dr. Jorge Salazar, Dr. Giorgio Aru and Dr. Larry Creswell.

The team put him on a transplant list in August 2015 and started him on the drug Milrinone for patients with advanced congestive heart failure. They waited for a donor match. “This time, it was less scary. We'd been down this road before,” Jo said.

Brad's transplant coordinator, Brennett Brown, was the first to connect Fitzgerald and his new heart the afternoon of March 30.

“The on-call nurse walked in and said, 'We have a heart for Brad,'” Brown said. “I'd just gotten off the phone with him to talk about his medications. I said, 'If you will allow me, I would love to take call tonight.'

“I called him back a little after 4 and made small talk, and then I said, 'What about a heart? You still want one? We have a heart offer for you, and it's a good one.'”

Some patients, especially those recently placed on a waiting list, are skittish when they get the “offer,” Brown explained. It was an offer Brad would not refuse.

“I told her yes, and then my phone died,” he said. “She called me back and asked how soon I could be at the hospital, and then her phone cut off. She called me back again. She was determined.”

Becky was in Perkinston in Stone County, watching their youngest daughter Jordan, a student at Southwest Mississippi Community College, play softball. Becky's phone rang. She yelled to Jordan on the field.

“Her team started cheering. Jordan went to pieces,” Becky said. “Her coach could hardly coach, she was crying so hard.”

They jumped in the car. Oldest daughter Sarah, a senior at Mississippi State University, raced from Starkville. Brad was about 20 minutes ahead of them. “I have a friend in law enforcement. I called him and said I have to be in Jackson. I've got to be there now. We were at the hospital before 6.”

They were swift. Brad's new heart wasn't. Severe storms that night in Mississippi delayed the arrival of Panos, who was in Oklahoma at a conference when UMMC physicians reached him. Panos had been tasked with traveling to the donor, inspecting and removing the heart, and transporting it back to Jackson packed in an ice solution that made it viable for just four hours.

“We do this on purpose so that we can actually see the organ. We want to make sure we get a good heart,” said Panos, the lead surgeon for Brad's transplant.

As Panos traveled to Jackson, Brad was wheeled to the OR and prepped for surgery at about 1:30 p.m. March 31 - knowing that if something went awry with the donated heart, he'd go right back to his room. “I trusted them to make the right decision,” he said.

“I was laying on the table, and the nurses asked me what kind of music I liked,” Brad said. “I like really old country, and I started singing along with some Waylon Jennings.” To his amazement, deShazo sang with him. “He could name all the artists as they came on. I was blown away,” Brad said.

When he woke up, “it took me a minute to realize where I was, and that I had a pipe down my throat. But I knew I'd had the surgery. It gets real really quick.”

“When Brad got so sick, I knew a transplant was coming. It was just a matter of when,” said Jo, a veteran cardiac surgery nurse who now works in pre-anesthesia testing. “But I knew he was in good hands, having already been through it with my father.”

Those hands included Brown, who worked closely with Jo during their earlier employment in cardiac care at Baptist. “She will always be special to me for that, and especially for her care of my daddy and now Brad,” Jo said.

Jo was wrapping up her day at Batson Children's Hospital at about 4 p.m. the day before the surgery. When her mother called with the news, Jo's thoughts rushed back to when she took the call about her dad's donor heart. Her mom, Shirley, was at Walmart.

“They were in a camper at the Reservoir, waiting for a heart. The hospital wouldn't let him go back to McComb,” Jo said. “I was staying with him for a couple of hours while my mother was shopping, and although most people didn't have a cell phone then, I did. I had to write a note to my mother and leave it behind when we left for the hospital.”

Nick Fitzgerald is 75 and knows his son has a new heart, but he has trouble communicating because of health problems unrelated to his transplant. It was Brad who, at age 26, drove his dad to the hospital in McComb after Nick suffered his third heart attack, a year before his own transplant.

“I'd drive, then stop and do CPR, then drive some more,” Brad remembered. After they reached the hospital, “the nurses said they had to shock him 17 different times,” Becky said.

Brad's team isn't surprised he's done so well. “He was the ideal candidate,” deShazo said. “He had no medical problems, with the exception of his heart failure. That's why he's bounced back so quickly.”

The Fitzgeralds' gratitude goes out to an extended family: Their relatives. The congregation of Friendship Baptist Church. The doctors and dozens more who played a role in the transplant. The donor's loved ones who, in their sorrow, were generous beyond measure.

“The girls have been able to experience their granddaddy because of UMMC,” Brad said. “The length of time I'm feeling amazing is getting longer and longer.

“I'm going to keep myself healthy. The wells can wait. I'm just so blessed to have this gift.”