For Dr. Bo Huang, the eyes have always had it

Editor's Note: A version of this story first appeared in the fall 2025 issue of Mississippi Medicine.

For young Bo Huang and others in China during the ’60s and ’70s, food and good times were scarce.

“There was no TV, no radio,” Huang said, “so, all I knew to do was to study in school, and after school I read more books; I was able skip quite a few grades.”

After one year of high school, the prodigy was accepted into medical school, and became, at 14, “the Doogie Howser of my day.”

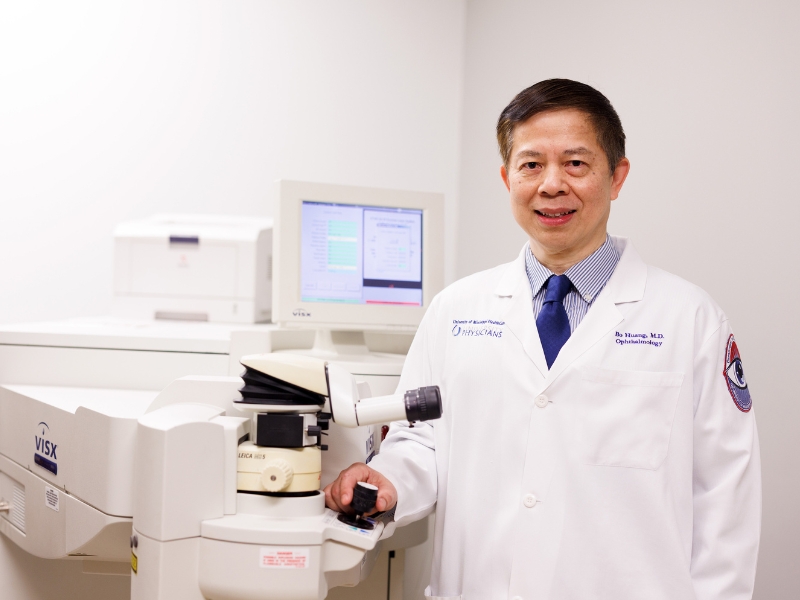

Even then, the future ophthalmologist had already found focus; today, Dr. Bo Huang, professor of ophthalmology, gives new life to the eyes of patients at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Huang loves a profession that brings so much joy. One of the joyful came to Huang early in his career, a patient who examined the eye chart and saw a swirling, rheumy mystery.

“A week later, after his surgery, he was 20/20,” Huang said. “He was so happy. I still remember him now, 20 years later.”

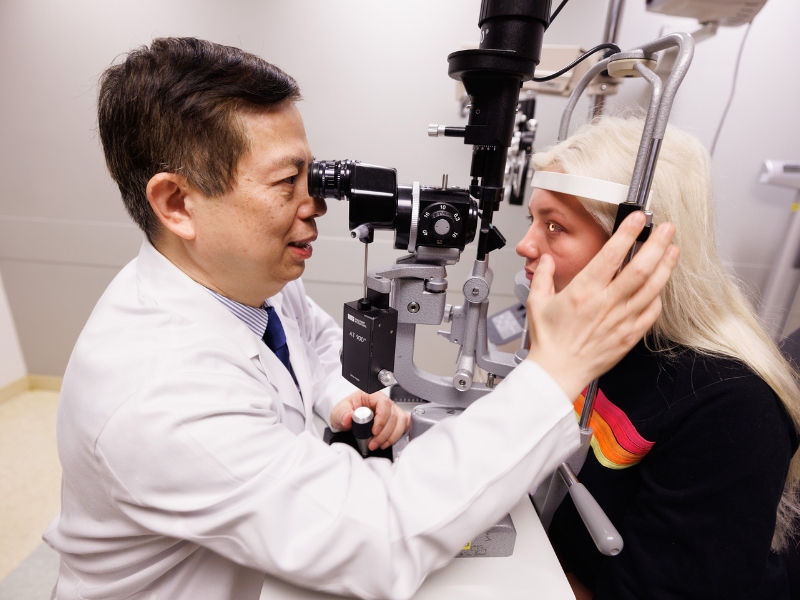

Many of his patients will always remember Huang, including Carly Jo Smith, 18, of Florence.

“Dr. Huang treated my severely dry eyes with tubes,” Smith said. “I was so scared the first time. But Dr. Huang talked me through it. He makes me feel very comfortable. And he’s so funny, actually.”

Those who enjoy that charming bedside manner might be deprived today if the Cultural Revolution hadn’t ended when it did. Communist China’s 10-year period of terror began in 1966, when Huang was about 2.

“People were very poor; they had to stand in long lines to get food,” said Huang, recalling his upbringing in a small town in southern China.

The death of the country’s leader, Chairman Mao, in 1976, meant the birth of Huang’s livelihood, more or less. “Before his death, your acceptance to medical school was not based on merit; it was reserved for children of the elite,” Huang said.

“Afterward, the Chinese government opened college to the general population.”

Huang passed an entrance exam and entered medical school in 1978. He graduated from Jiangxi Medical College in 1983; he was 19.

He would not end his post-graduate studies for another two decades, ever keen to raise his sights.

And, yet, it was the eye of a frog, or perhaps a newt, that first caught his – eye, that is.

Windows to his soul

One of three children, Huang was brought up by a Chinese literature teacher, his dad; and a nurse, his mom.

“My mom always wanted me to be a doctor,” Huang said. “And I saw how hard she and other nurses and doctors tried to save lives.” Including Huang’s.

“When I was young, I had health issues mostly related to malaria,” Huang said. “I was hospitalized a lot. That also had a pretty big impact on my decision to become a doctor.”

Research also riveted him. After earning his medical degree and then a master’s degree in immunology – thank you, malaria – he moved to the U.S. and began a PhD in neuroscience at the University of Georgia.

“I studied the photo receptors of small amphibians,” he said. “Dissecting their eyes led to my interest in microsurgery.”

That experience led him to another revelation that electrified his career. “It fascinated me that you could have the ability to save people’s sight,” he said.

Saving people’s sight often means removing cataracts – the clouding of the eye’s lens.

“Dr. Huang does most of the complex cataract cases in our department – and in the state,” said Dr. William Watkins (’08), UMMC associate professor of ophthalmology.

Cataract surgery is relatively simple today, Huang said. “But when I started years ago, you had to make a very big incision on the eyeball to remove the lens, then multiple surgeries followed.

“You expressed the whole lens, which could cause damage to the surrounding tissue. The eye was prone to infections. People stayed in the hospital for days, and it took weeks for the vision to recover.”

Today, surgeons make a small incision – no sutures needed. An ultrasound device sucks out the lens; it’s replaced with an implant. “The next day, the patient’s vision is 20/20,” Huang said.

It’s one of the many pleasures of his job. “I enjoy having an academic practice. I get to do research with other colleagues in the field,” said Huang, whose studies have been published widely.

“I get to teach residents and see them become practitioners on their own.”

One future medical resident is very close to him. Huang’s son, David, is second-year student who has conducted research.

Bo Huang’s many loves have apparently infected his son; beyond science and medicine, those include traveling to faraway places. When it comes to that, Bo Huang and his wife, Lin “Jenny” Huang, are very much in step.

Windshield of the eye

Huang and the late, legendary Dr. C.J. Chen had much in common, including the waltz and Latin dance.

“I met my wife at a ballroom dance party,” Huang said. “She introduced me to the wonderful world of ballroom dance.”

Bo and Jenny Huang have traveled as far away as Shanghai to compete – a passion that was shared by Chen and his late wife, ophthalmologist Dr. Lin Chen.

Long before C.J. Chen passed away, in 2023, he became the UMMC ophthalmology chair and recruited Huang.

“Dr. Chen gave me the opportunity to get ahead and also do research,” Huang said. They met in 2002, the year of Huang’s fellowship in cornea and refractive surgery at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

By 2003, he was headed to UMMC, bringing with him a neurobiology post-doctorate; surgical internship; and ophthalmology residency. Joining the UMMC faculty the same day was Dr. Kimberly Crowder (’99).

“From the day Dr. Huang arrived here, he was absolutely the faculty member who would say, ‘yes’ to everything – to teaching and research opportunities and always to patient care,” said Crowder, UMMC professor and Drs. C.J. and Lin Chen Endowed Chair for Excellence in Ophthalmology.

“He has gotten a lot of calls on Friday afternoons from doctors outside the Medical Center who know he’ll help them with patients who have corneal ulcers.”

He is known, in so many ways, for being quick on his feet.

Huang has been particularly quick, and good, at preserving the sight of his colleagues’ moms – Watkins’ mother, for one, with a cornea transplant, and Dr. Albert Lin’s, with cataract surgery.

Huang is one of the best cornea specialists, “if not the best,” in the state, said Lin (’11), associate professor of ophthalmology.

“When it came to learning how to suture the eyes, a lot of what he taught rubbed off on me.”

Huang also brought to UMMC his expertise in endothelial keratoplasty – a less invasive procedure for transplanting part of, instead of the entire, cornea, Crowder said.

“He was the first in the state to do those transplants.”

The cornea, described as “the windshield of the eye,” lets precious light in and keeps malicious stuff out – a metaphor for the life and career of this distinguished healer of the human eye.