Allaying pain, affirming life: Palliative care team meets patients in their 'sacred place'

Darrell Roe was in his hospital room with his mother and their pastor when a group of strangers carrying sitting stools entered, surrounded Roe’s bed and sat down.

“They invited Darrell’s mother and me to sit in the circle with them,” said the Rev. Vicki Landrum, the Roes’ minister. “It was like we had a little campfire group around Darrell.”

The visitors, many wearing white coats, began asking Roe questions; and then they did something truly remarkable, Landrum said: “They listened.”

They listened to a patient who, at only age 53, is struggling with the same heart condition that took his father’s life, but won’t give in to despair: “I’ll either wake up each day hearing Wynton Marsalis playing ‘What a Wonderful World’ or Gabriel blowing his horn,” he says. “Either way is a good day for me.”

Roe is not facing this crisis alone, however, thanks to his family, friends, church and the group of people who came to his room at the University of Mississippi Medical Center: the palliative and supportive care team, whose members were there to hear his worries and wishes, to help him see his future through the lens of a serious disease.

Led by Dr. Keith Mansel, professor of medicine and director of the Hospice and Palliative Medicine Fellowship Program, the team here is part of a movement driven by the needs of a population that, because it’s living longer, has longer to decide how to meet death, and what matters in the end.

To help patients make that decision, they are such questions as: What are you hoping for?

“That isn’t a clinical question,” said Mansel, whose core team members are Dr. Dan Woodliff, associate professor of medicine; Carole Ward, RN, palliative nurse navigator; and Linda McComb, hospital chaplain.

“Patients rarely say, ‘I hope my [lab test results] are better.’ They say something like, ‘I hope to see my only grandchild graduate from college.’”

‘A WONDERFUL THING’

Palliative care helps people deal with serious, life-limiting illness.

It is related to, and may include, hospice, which treats patients at the end of their lives, those who are expected to live no more than six months.

It is about deciding what kind of care a person will receive – the kind meant to extend life, or a less aggressive program focused more on quality of life. It’s about making the patient more comfortable physically, emotionally, spiritually; it’s about affirming life.

This is how Roe would like to affirm his life: Rather than lying in a hospital bed or in a nursing home, where he has also spent time lately, the computer technician prefers to be at his home in Pearl relaxing in the recliner with his dog.

The palliative care team has discussed with him ways he can do that, including making physical modifications to his home.

“These are people who work at a hospital, but who are trying to help him stay out of the hospital,” said Bobbie Roe of Pearl, Darrell Roe’s mother. “It’s a wonderful thing they’re doing.”

The team members, as they gathered around him in his hospital room, brought him a welcome measure of warmth and comfort, Darrell Roe said.

“They talked to me about who I am and what I like to do, and what my expectations are. It was very reassuring – just knowing there are people who deal with this, who know how to get things done.”

More and more patients across the country are benefiting from this type of care. Mansel said. “At one time, people were more likely to die suddenly – from a heart attack, in a car wreck. Or they died quickly from cancer or kidney disease within weeks or months.

“That still happens. Happily, through technological innovations and changes in lifestyle, people are living longer. However, the burden of illness, frailty and diminished quality of life, may make medical decisions more challenging than in the past.”

For some, the price of an extended life may not be worth it.

‘ALWAYS, ALWAYS CARE’

Studies show that around eight out of 10 Americas would rather die at home, if possible, reports the Stanford School of Medicine. Yet, 60 percent of them die in acute care hospitals; 20 percent in nursing homes. Only 20 percent die at home.

Reasons for the gap, Mansel said, include lack of health insurance coverage, but also a lack of communication. “We don’t have this conversation between patient and physician often enough.”

That dialogue is vital for avoiding false assumptions.

“When I believe the end of life is near for patients, and they say, ‘I want everything done,’ that word ‘everything’ is often different from what a physician thinks it is,” Mansel said.

“It doesn’t necessarily mean staying in the ICU for four months. It may mean living long enough to say ‘goodbye’ to everyone.

“In palliative care, we try to help people figure out where they’re going, what’s going to happen to them.” With that knowledge, they can better decide how to live out the rest of their lives.

As the decision is being made, a palliative care team serves as a kind of go-between for patients and those physicians supervising their care, to foster a climate of “clarity, transparency and decision-making,” Mansel said.

“Physicians are trained to take care of problems. It can be disheartening to them to realize that here is a problem they can’t fix.

“But we are better at these conversations than we used to be,” said Mansel, who describes ways to broach end-of-life issues in a textbook he co-wrote and which was released this year: “The Making of the Ideal Physician.”

The three authors are former colleagues from the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine & Science, where Mansel had trained in internal medicine and thoracic medicine and, years later, completed a fellowship in palliative medicine. He also worked on the palliative care staff until 2016, the year he returned to his School of Medicine alma mater, UMMC, and to the city where he once had a private practice.

Along with Dr. Edward C. Rosenow III and Dr. Walter R. Wilson, Mansel stresses to physicians and medical students the importance of caring and professionalism. In Chapter 14, a treatise on palliative care, Mansel posts a list of goals, such as offering relief from pain, affirming life, and responding to the patient’s psychological and spiritual needs.

He writes: “Never take away your patient’s hope by saying, ‘There is nothing more we can do,’ or, ‘We are withdrawing care.’ We always, always care for people. There is always more you can do. You can continue to care. And listen.”

Landrum, pastor of McLaurin Heights United Methodist Church in Pearl, is particularly attuned to the spiritual needs of congregants like Roe. Her late father underwent hospice care.

”I was really impressed with the palliative care team,” she said. “Maybe they had entered the room with their minds made up that hospice needed to happen for Darrell, but, as they listened to their patient, they realized that’s not where Darrell is right now.

“That’s the most loving support you can give: Meeting people where they are and helping them take the next best step. It’s enormous to think about all the decisions that need to be made. I’ve learned a lot from people who are at the end stage of life.

“I know that when you are with people at this place in their lives, it’s a very sacred place.”

‘A TIME OF REMEMBRANCE’

In the spring of 2017, James Malone of Vicksburg had become terminally ill. Other than his wife Betty Malone, no relatives lived nearby.

His sister Anne Malone, who lived outside of Chicago at the time, traveled from Illinois to Mississippi to be with him for several days and to meet with Mansel and Ward some months before her brother’s death.

“Dr. Mansel and Carole made a very difficult time so much easier than it would have been otherwise,” Anne Malone said. “They helped me and my sister-in-law sift through the options for hospice care, and in a very gentle way helped us make what I believe was by far the best decision.”

At that point, her brother could not communicate very well, she said. “But both of them asked a lot of questions about Jim; they took a personal interest in him and our family, which was to us so welcome.”

Because of the answers they got, Mansel and Ward knew the patient as someone more than a 72-year-old stroke case with pancreatic cancer. They knew him as a quiet, private man, a music lover who collected stamps and loved to read.

Similarly, the palliative care team has come to know Darrell Roe as someone more than a case with a heart condition. At his church, he served as chair of the board of trustees and helped the Boy Scout ministry become reinstated.

He has been the church’s “computer guru,” Landrum said, and worked in the food pantry. He enjoys cooking.

Getting to know a patient, even if only through a handful of personal details, takes a toll on the palliative care providers. They have their own emotions to confront.

So, every Friday, members of the team get together, often with other care givers who have worked with them. Mansel calls it “a time of bereavement and remembrance.”

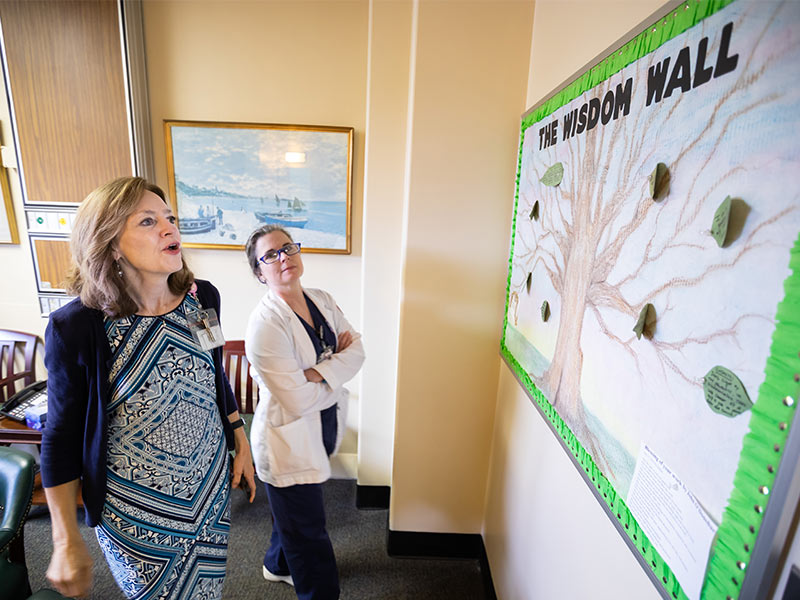

During one of these meetings in August, a husband-and-wife couple, Dr. Zach Pippin, a hospice and palliative medicine fellow, and Dr. Kelly Pippin, chief resident in internal medicine, joined Woodliff, McComb, Mansel and Ward.

Overlooking the meeting room’s conference table is the “Wisdom Wall,” a bulletin board posted with “leaves” of wisdom – words of insight spoken by patients and families – and hanging from a drawing of a tree. Among the foliage are Roe’s words about the Angel Gabriel and his trumpet.

And this, from another patient: “We are all cousins.”

Near the tree, there is talk, not of IV’s and meds and the challenge of comorbidities. Instead, there are stories quietly told of the 36-year-old mother of three who loved to sing and dance before she suffered neurological ruin; the railroad worker who enjoyed cooking before a tragic fall changed his life; and the man who lived in a yellow house.

“I will not forget his smile,” Ward said.

Besides the patients are their families, who also “don’t know what lies ahead for them,” Ward said. “There may have been a horrific accident, and now they’re just trying to make it.

“But I do see wonder and awe in the simple grace with which they get through the day.”