Minister, SHRP faculty member unequivocal civil rights champion

The Rev. Ralph Edwin “Ed” King is the grandson of a Mississippi sheriff, but if certain white cops had found him alone at night in a car, he said they might have killed him.

The Warren County native’s crime at the time, the ’50s and ‘60s, was to be a civil rights worker, a white minister advocating for black voting rights, an undertaking that, in those days, made him respected among some of his peers but a suspect among some within his race.

Perhaps he was better known in those days, but his name still resonates with civil rights veterans, historians, scholars and journalists, as well as some students and faculty colleagues at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, where he joined the School of Health Related Professions in 1974.

“He is a classic example of a civil rights activist,” said Dr. Stephanie Rolph, associate professor of history at Millsaps College, one of the institutions that cultivated King’s sense of justice.

“They were behind the scenes, often unrecognizable, doing the real work that goes into organizing. Most were not Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X or Rosa Parks or Fannie Lou Hamer,” said Rolph, whose specialty is civil rights history in the South. “They were people on the ground, producing flyers, going door-to-door, laying the groundwork.

“Ed King is very quick to point out those he thought were more dynamic than him and who haven’t gotten enough attention. He deflects the attention away from himself.”

Certainly, he tried to do so in a recent interview on the UMMC campus, where the retired minister of the Mississippi Conference, United Methodist Church, occasionally lectures, retaining what amounts to a courtesy appointment as associate professor of clinical health sciences in SHRP.

“I was in jail less than a dozen times,” said King, 81, who grew up in Vicksburg. “Some of my black friends were in jail at least 40 times.

“Violence was just part of it,” he said, at one point adjusting a necktie and collar covering his scarred throat.

The brutality King and others encountered was a reaction, in part, to the 1963 Freedom Vote, part of the effort to restore suffrage to disenfranchised black citizens. A century after the Civil War, many white Southerners were still challenging the federal rule of law.

Some of those activists were martyrs, people King knew, such as the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Medgar Evers, the state’s field secretary for the NAACP.

“Medgar became the older brother and teacher,” King said. “And Martin must have felt somehow that this white Southerner was worth redeeming.”

Evers was one of the fellow Mississippians who urged King to come back home after his studies in Boston.

“I had assumed I couldn’t return because of my views,” said King, who helped organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, a proposed antidote to the regular, segregationist Democrats.

“By the time I was 10 or 12 in Vicksburg, I had realized that America had not figured out yet how to deal with our history of slavery and continuing racism.”

His convictions were reinforced while he was a sociology major at Millsaps College in the 1950s. He attended academic programs at nearby Tougaloo College, where he met an influential sociology professor, Ernst Borinski, and Evers.

For King, the Sunday school and mission teachings also held sway and opened him up to the words of Martin Luther King Jr., whose messages on the power of love and nonviolence echoed those of Jesus Christ and Mahatma Gandhi.

He joined the movement, organized sit-in demonstrations, watched as his segregationist parents were run out of the state for having a “Communist” son, served jail sentences in Mississippi and Alabama, labored in black-and-white stripes on a prison work gang, and finally re-settled in Mississippi, becoming chaplain of Tougaloo College, where he saw Evers alive for the last time on a June night in Jackson in 1963.

“We were in the foyer of a small church,” King said. “He had been tormented by a decision he had to make: whether to ask Martin Luther King to come to Jackson. He believed he would lose his job with the NAACP if he did.

“But that night, he had decided to invite him, and he was at peace with it.”

Hours later, Evers would be shot down in his driveway at his Jackson home.

“When Ed King and other civil rights workers tell you their impressions of violence, fears of violence, fears of death, you may wonder, ‘Is this exaggerated?’ The short answer is, ‘No,’” said Dr. Trent Brown (formerly Trent Watts), who grew up in McComb and Brookhaven and is coauthor of Ed King’s Mississippi: Behind the Scenes of Freedom Summer.

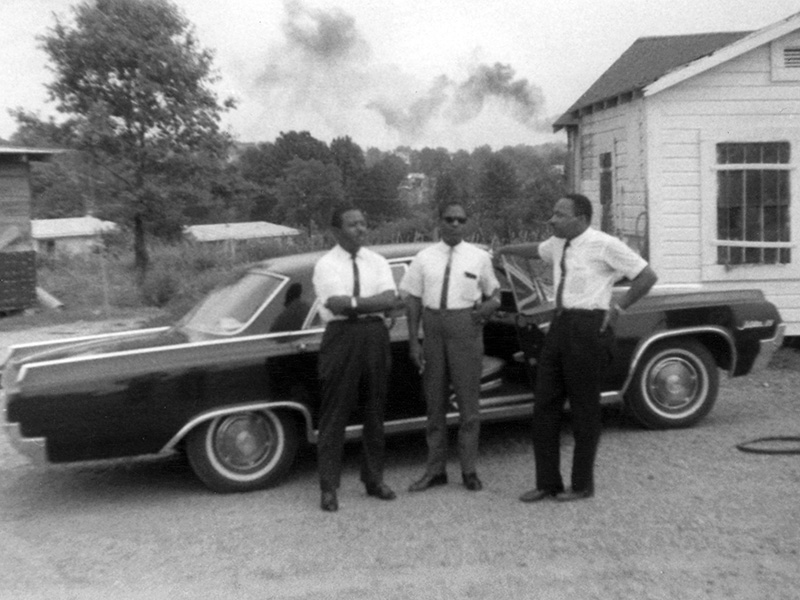

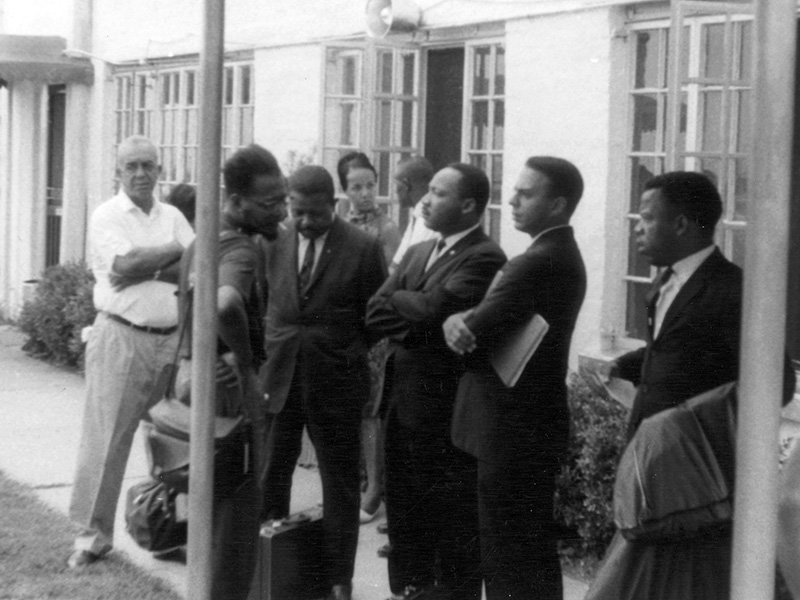

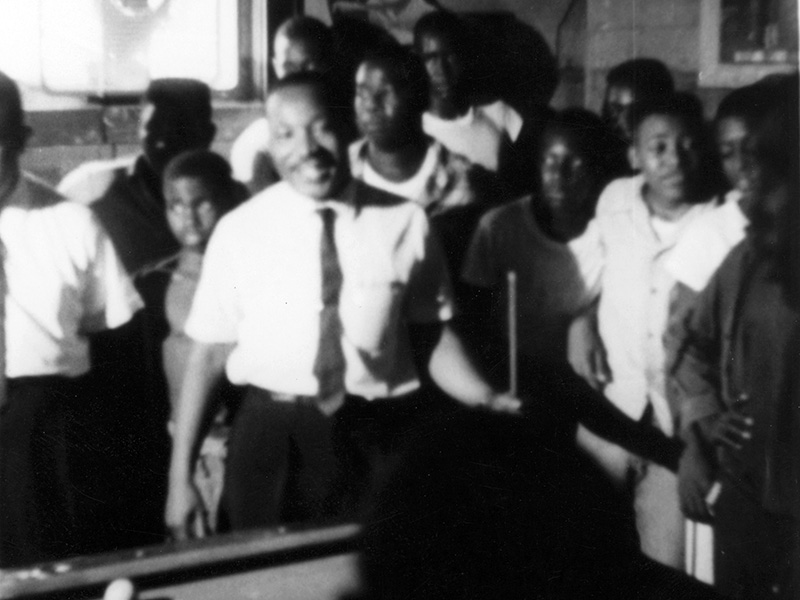

Published by University Press of Mississippi in 2014, Ed King’s Mississippi is a collection of about 40 photographs King took during the crucial summer of 1964. It includes his written impressions of the work done by Martin Luther King Jr., Freedom Summer volunteers and the local people.

Brown, professor of American studies at the Missouri University of Science and Technology, knew of King’s contributions to the movement and proposed the book’s concept.

“It’s hard to exaggerate the dangers that people like Ed King and the other civil rights workers faced,” Brown said.

The stories behind those dangers are on display at the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum in Jackson. Among the activists featured is King who, on a recent museum tour, presented an impromptu speech on the Amistad slave revolt to a group of visiting students from Brown University. In 10 minutes’ time he had linked that rebellion to the history of Tougaloo College.

The National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis also honors his contributions, naming King an “Icon of the Movement.”

“What’s remarkable to me about Ed King’s past is that he could have taken a church, he could have taken an easy path through the decades,” Brown said. “He could have at least chosen a less confrontational path. Most people did.

“He saw something that spoke to his conscience, his faith, and said, ‘I know what I have to do,’ and he did it, and suffered for it.”

Those who attacked him were “the usual suspects,” King said without elaborating. His car was run off of a road. He was chased. He was a passenger in a car that was crushed from the side by a speeding vehicle. He was hospitalized several times. Part of his face has been reconstructed.

“We were grassroots, and that’s a threat to the people who run the world,” King said. “Only if they can predict your moves will they tolerate you.”

By June 12, 1963, Medgar Evers had become intolerable to some, King said, and died for it. “There are many legends about what happened that night.”

One says that after Evers was shot, it took a long time for police officers to arrive and, then, the Medical Center at first refused to treat him. King believes those notions were part of a civil rights narrative in which others elsewhere were actually treated that way, assumptions were made or the details migrated to the story of Evers’ death.

In this case, the details were untrue, he said.

“The police thought it would take too long to wait for an ambulance, so they used a mattress brought from one of the children’s bedrooms to carry Medgar to a neighbor’s station wagon,” King said. “They took him to the Medical Center. He was not turned away.

“The University of Mississippi Medical Center did everything possible to save the life of my friend.”

Today, at that same institution, King, who completed a fellowship at Harvard Divinity School and has master’s degrees in theology and in social ethics from Boston University, speaks to students on such matters as medical ethics and the social factors of health care. He fields requests from Dr. Ralph Didlake, UMMC associate vice chancellor for academic affairs and chief medical officer, to archive King’s papers at the Medical Center or in collaboration with other institutions.

“Right here on campus we have a direct participant in events that shaped our nation,” Didlake said. “He has made such contributions to the Medical Center community and to the community at large. We are obligated to preserve this important history.”

King persists in recording that history. Among his projects is research for a book about poverty, national politics and race. “These issues that are still with us,” he said. His material has been published in the Mississippi Writers Series from University Press of Mississippi, as well as in other books and journals.

“In that regard, he is different from some who enlisted in the movement and bear the scars,” Rolph said. “Like war veterans, that time in their life was traumatic. Ed King has filled the vacuum left by others who won’t talk about it, or who didn’t survive. He’s unique in that way. And he has maintained a fabulous amount of humility about the work he did.

“There is just nobody else like him.”