Students, faculty, poetry buffs, old radios in good hands with Didlake

Published on March 16, 2017

NOTE: This article originally appeared in the Winter 2017 issue of Mississippi Medicine, the semi-annual alumni magazine for the School of Medicine. A PDF of that issue can be found here.

Dr. Ralph Didlake is known for his talents as a physician, professor, academician and administrator. But the trained surgeon is less known, perhaps, for his skills at dissecting poetry and stitching back together World War II-era radio receivers. A profile of the New Mexico native with Mississippi roots, math whiz and - according to him - “probably the worst football player in the history of Crystal Springs.”

It's unlikely that Dr. Ralph Didlake Jr. would be the person he is today in a world that never experienced the Civil War, the Nuremburg trials, the harnessing of electromagnetic waves, nuclear tests, the Space Race and the poetry of Sylvia Plath.

But, then, who would be?

Still, each of these monumental spectacles, movements or events has had a direct personal connection to his life or lineage, shaping the character, career, hobbies and habits of this physician, professor, academician, administrator, ethicist, poetry commentator and radio repairman.

“My career looks like a bad case of attention deficit disorder,” said Didlake, trying to identify a defining moment in his life and profession.

To others, it looks like a good case of intellectual versatility.

It's a cliché, but it's true, said Sondra Redmont: “He's a Renaissance man.”

He bridges his love for the humanities with medical education, “providing a context for our students,” said Redmont, director of operations for the Department of Preventive Medicine and Data Science.

It was as a medical student that Dr. LouAnn Woodward first encountered Didlake, when he was the program director for general surgery.

Now, as leader of the Medical Center, she has developed an even deeper regard for his talents.

“He is thoughtful, wise and cares deeply for the education process, the education environment, and for our learners,” said Woodward, vice chancellor for health affairs and dean of the School of Medicine.

“I rely on his counsel and trusted judgment every day.”

Didlake exerts his counsel and judgment as professor of surgery, associate vice chancellor for academic affairs, chief academic officer and director of the Center for Bioethics and Medical Humanities - the program for which he and Redmont created a summer fellowship for undergraduates. To direct the center full-time, Didlake eventually gave up his practice, Redmont noted. “And when he was asked to be vice chancellor for academic affairs, he accepted the challenge - which speaks volumes about his dedication to the institution and who he is.

“It takes a certain kind of person to be a surgeon; they save people's lives. But he's very humble. He's someone who listens. He's someone who brings people together.”

He's someone who was taught to “never refuse a combat assignment,” he said, quoting a line from “The Right Stuff,” Tom Wolfe's account of America's early space program.

That reference resonates with Didlake. The son of Ralph Sr., an Air Force chief master sergeant, and Lorraine “Dot” Didlake, he lived his early life on or near Kirtland Air Force Base in New Mexico, as did his sister Pamela, now a retired teacher whose married name is Brewer.

Their neighbor was a nurse who worked in the Lovelace Clinic, the guinea-pig lab for about 30 of the original astronaut candidates, yielding the ground-breaking Mercury Seven.

Didlake was brought up among the proving grounds for America's vision of greatness, and he reveled in this environment.

“For the early space flights, there was wall-to-wall news coverage,” he said, “and we were all glued to the seven-transistor hand-held radios.”

For the first 12 or so years of his life, starting in 1953, his home was in Albuquerque, a place rich in Old Spanish and Native American cultures and the arts, he said.

“Living there profoundly influenced my choices,” he said. “It provided an education base I value highly. The combination of arts and culture and science was seamless.”

From Albuquerque's public TV station, KNME, he soaked up the weekly adventures of the mustachioed Dr. George Fischbeck, an enthusiastic science popularizer in glasses and a bowtie.

“The area was home to physicists, nuclear engineers, mathematicians,” Didlake said.

Many of those scientists worked at nearby Los Alamos, the site of more than a dozen nuclear tests witnessed by his father after World War II - brilliant flashes of light, and clouds of destruction hanging over the desert like puffy stalks of broccoli or massive human skulls.

“My father felt very strongly that the nuclear program was important to the defense of the country,” Didlake said, “but it was also counter to his persona. He was a very peaceful guy.”

Peaceful enough to oppose his son's brief interest in a military career during the Vietnam War. At any rate, by the time the family left New Mexico, Didlake's trajectory pointed toward medicine, and to his roots in Mississippi.

Family, football and fate

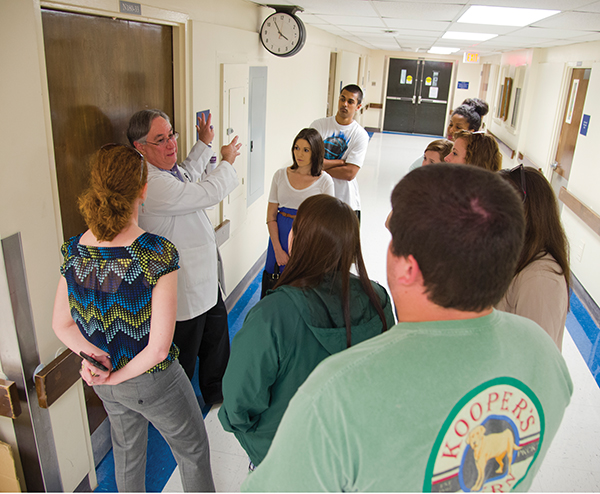

Leading a Millsaps College history class on a historical tour of UMMC in April 2014, Didlake shows students the original ER area where civil rights leader Medgar Evers was brought after he was shot in June 1963.

In Copiah County, between County Line Road and Old Highway 27 Road 1, past a smattering of houses and barns and stands of trees, is a thread of pavement called Didlake Road.

Nearby is the centerpiece of Cherry Grove Plantation: a house with a four-columned portico, gabled roof, fan-lighted entrance and pine floors - all built in the mid-1800s by the hands of the forbear William H. Didlake.

Even before the Civil War, the Crystal Springs area had been a hive of Didlakes, nurturing Ralph Sr., and even Dot in her youth. But, sometime after Reconstruction, the family gave up their ownership of, if not their affection for, Cherry Grove.

“We used to make an annual pilgrimage there,” Didlake said.

“Initially, there was a sense of deep heritage and connection to the state and its history.” But the foundation of his identity was shaken with the force of a rocket launch “when I realized I was a descendant of slaveholders.”

He awakened to that fact during college, he said, “but I started to reflect on it deeply when I began this journey to study bioethics and humanities.”

That journey became inevitable when Ralph Sr. retired and moved his family to Copiah County, where his son played right guard for the high school team and became “probably the worst football player in the history of Crystal Springs.”

Thanks to a quirk in class scheduling involving last period, he had to play football, he said, or he wouldn't have been able to take advanced math, a course that would help prepare him for college.

In contrast to the Albuquerqueans he had known, some of his neighbors here defined the pinnacle of success as “playing varsity football and getting a job at the local transformer factory,” Didlake said.

Mississippi had its advantages, though. “There's the Southern culture, the storytelling tradition,” he said. “I value that part of my upbringing, too.”

Still, nuclear physicists were scarce down Cherry Grove way. There were no Dr. Fischbecks, either; but there were, to Didlake's relief, Dr. Mark Puryear and Dr. Tom McDonnell, two M.D.s in nearby Hazlehurst.

“They were among a group of physicians who were such an integral part of the community,” Didlake said. “They fit my notions of what a physician should be.”

Those notions began to take shape in his boyhood, when he was drawn to stories about explorers such as Jacques Cousteau and Thor Heyerdahl, whose work mixed adventure with science. No wonder he became a surgeon.

And here he was able to identify a defining moment: “The first time I observed a surgeon at work,” he said. “It was like watching a clock. It all worked together.

“It's a blend - of science, of using your hands, of creativity. And, if there was a problem, it got fixed.”

His mentor, Puryear, did some surgery as well, and this certainly influenced Didlake, who eventually landed a job as an operating room tech to pay his way through the university and then as a medical student at UMMC.

“Working in the OR seemed far more exciting than seeing patients in a clinic,” he said.

And then the excitement ended, amid a brilliant flash of insight.

Drug deal gone good

Beyond the cadre of Copiah County physicians, people who have left a significant imprint on Didlake's career and/or spirit include his father.

“He had a big sense of duty,” Didlake said. “But he made it look easy: You just do the right thing.”

If that lesson needed reinforcing, his older cousin, Mary Frances Kitchens, chimed in, he said. “Also, she would encourage you to step outside your interests. Because that's where the greatest rewards are.”

Most recently, he accepted the counsel of a former emergency room nurse he had had gotten to know in the early '80s, when he was a Medical Center surgery resident. He and Millie Faith McDonald did not meet “cute.”

“We met over a young man who had been shot six times in a drug deal,” Didlake said. Following their marriage in 1983, their three children, a son and two daughters, were all born over the next five years.

In the meantime, Didlake finished his residency, in 1985, took his family to Houston, Texas for his two-year organ transplant fellowship and came back to the Medical Center as “the last Hardy-trained surgeon hired on as faculty,” he said, referring to the late transplantation pioneer, Dr. James Hardy.

Around the turn of this century, Didlake departed UMMC again, taking on a private practice in the Jackson area, until surgery seemed “very much like an assembly line,” he said.

He was wistful for the academic world - “that was 90 percent of it.”

In 2008, the orbital energy of the Medical Center pulled him in again, and he returned this time with a charted course “that was going to carry me into the sunset,” he said.

“Enter LouAnn Woodward.”

‘A terrible idea’

A versatile polymath, Didlake jokes his career "looks like a bad case of attention deficit disorder."

Millie Faith Didlake's advice to her husband was this: Go back to school.

So he did, to Chicago's Loyola University, where, six years ago, he earned his MA in bioethics and health policy.

For years, he said, “I was as happy as I could be operating all day long. But, then, I started to mature as a physician. In medical school, I had been aware of bioethics, but had no interest.”

The study of bioethics is fallout from the Nuremburg Trials, the post-World War II scrutiny of Nazi doctors' experiments on humans. Those practices, along with such post-war advances as heart bypass surgery and ICUs, compelled the world medical community to set boundaries for humane research.

To that end, physicians and others often heed the voices of philosophers, theologians, artists, writers, musicians. Didlake taps into their wisdom for the benefit of his bioethics fellows.

As a physician, he was stirred by the ethical quirks of medical care midway through his surgical career, when many of his patients were on dialysis.

“They all received the same, exact treatments,” he said, “but one would do well, while the other would not. Their circumstances - social, economic - could change the outcome.”

This revelation struck him at a time when he was also “restless and bored.” That's when his wife “insisted” he study bioethics.

But he did more than that. At UMMC, he created his new, dream job by securing funding for the Bioethics Center and coming aboard as director. But Dr. LouAnn Woodward, who was associate vice chancellor for health affairs at the time, wasn't about to let this polymath off so easily.

She asked him to sweeten his resume, as the new associate vice chancellor for academic affairs.

“I thought it was a terrible idea,” Didlake said. “But I have a deep respect for Dr. Woodward, so I decided to step in; and let me tell you, it was a steep learning curve.

“The thing I didn't realize at first was that, compared to being in the operating room and taking care of one patient at a time, in this role you can take care of thousands.

“I've been here 41 years, and I've never been more excited here than I am now.”

Still, once you've been a surgeon, your hands can get itchy.

Party like it’s 1952

Didlake made his full-time return at the Medical Center in 2010; that was the last year he performed surgery.

“I do miss the environment of the operating room very much,” he said, “and the immediacy of the result. As an administrator, I can craft what I believe is a perfect policy, but won't know for two years if it is perfect.”

Today, he operates on machines instead of people. Besides woodworking, in the shop behind his house in Madison, he restores antique radios. Among his vacuum-intubated patients is a prized radio receiver that was standard in medium and heavy World War II-era bombers - the kind whose explosive cargo draped the skies over New Mexico.

“I'm perfectly equipped for life in 1952,” he said. “I could run a radio repair shop in 1952.”

To the extent that he can, he fills the surgeon's void this way. “It's the only skill I could fall back on,” he said.

“It's working with your hands, and the blend of science.”

And, if there's a problem, it gets fixed.