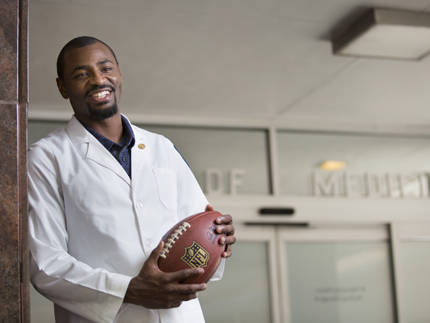

Former NFL receiver runs indirect route to medical school

Among the many colors Nathaniel I. “Nate” Hughes II has worn to work are the teal and gold of the Jacksonville Jaguars and the Honolulu blue of the Detroit Lions.

But the shade that matters to him most today is the white of his coat, the uniform he donned a year ago as a member of the medical school class of 2019.

“As an NFL player, he didn't let the limelight get him off track, and I find that extraordinary,” said Dr. Claude Brunson, professor of anesthesiology, senior advisor to the vice chancellor for external affairs and a member of the admissions committee that considered Hughes' medical school application.

“The committee knew he would have a lot of experience and maturity to offer,” said Brunson, who has helped vet applicants for about six years. “There was not much doubt that he would be a good addition to the class and a very fine physician.

“For my term, he's the first NFL player in medical school here that I'm aware of. We always look for a student who will add something different to the mix, and certainly he will do that.”

Named as one of the Top 50 Greatest Football Players at his alma mater, Alcorn State University, in 2014, Nate didn't grasp the scope of his potential until he was a senior in college.

“I was headed to the offensive coordinator's office one day,” he said, “when two NFL scouts walked out. I asked the coach who those guys were there for. He said, 'They were here for you.'”

Various sources, including the NFL, report that only 1.6 percent of college football players make it to the pros. In in the end, Nate was not drafted. But after impressing some teams during tryouts at a rookie mini-camp, he was tempted with a free-agent contract from the Cleveland Browns.

He succumbed. “But I told my daddy it didn't matter how much money I made, I still wanted to go to medical school,” Nate said.

His father is Nathaniel N. Hughes, a certified registered nurse anesthetist at UMMC who also played football at Alcorn; whose other son, Charles, plays football and runs track for Alcorn; whose daughter, Morgandy, graduated last year with a nursing degree from Alcorn; and whose loyalty to the purple and gold is rivaled by his and his wife, Gwendolyn's, devotion to their children's education.

“We put pressure on all of our kids that, if they do sports, they have to maintain their academics,” said Nate's father, who became friends with Brunson in the operating room long before Nate was old enough for college.

“I had the opportunity to watch Nate grow up,” Brunson said. “I was very impressed with how his parents kept him focused on his education, even when he was in the NFL.

“Nate's dad would give me updates in the operating room: 'He's doing fine; he's not blowing his money.'

“I believe he helped Nate understand that playing in the NFL doesn't last. It's for young people. Then you have to have a job.”

Nate is 31. He didn't really begin dreaming about life in the NFL until he was in his 20s, but he had been dreaming about life as a physician since he was a child.

A native of Macon, he attended nearby Starkville High School, where he starred in football and as a hurdler in track-and-field - which he describes as “my true love.”

His grades and athleticism earned him scholarship offers, including one from Stanford University, but his father and grandfather persuaded him to take his talents to Lorman.

“I told him I know Stanford is a good school and has some things Alcorn doesn't have, but Alcorn has some things Stanford doesn't have,” Nate's father said. “Finally, I said, 'the way I look at it, Nate, you've got two choices and either one is all right with me: You can go to Alcorn, or you can go to Alcorn.'”

At Alcorn, Nate thrived under the tutelage of then-head football coach Dr. Johnny Thomas, a former ASU linebacker who shredded running backs and earned the nickname “Ripsaw.”

“I called Nate 'Medicine Man,'” said Thomas, chair of ASU's Department of Health, Physical, Education and Recreation. “That was because of his intellectual diversification, his optimum performance in both academics and athletics.

“To be in the medical field as a football player and do extraordinarily well, that's very special. I have a tremendous respect for the young man.”

During Alcorn's football season, Nate drove 30 miles to practice every day to Lorman from the university's Natchez campus, where he was studying for his nursing degree. A few years later, he would earn a master's degree in nursing as well.

“I wanted to get a nursing degree first to get clinical experience,” he said, “but it was always my plan to go to medical school. I was sidetracked by football.”

A standout receiver and punt returner at ASU from 2003-07, Nate was not sidetracked in college, though. He graduated from nursing school in 2008, as planned. That same year, he played in his first regular-season game in the NFL, with the Jacksonville Jaguars.

In spite of the Jaguars' loss to the Baltimore Ravens that day, Nate's debut was sweet. He had been cut by a couple of teams, including Cleveland, before he found a temporary home in Jacksonville. He played most of the following season.

Ironically, it was at one point during his career as a wide receiver that he also snagged a large chunk of clinical experience - during the 2011 NFL lockout, a work stoppage that shortened summer training camp, but gave him a chance to work full-time for about three months as a nurse in his hometown of Macon.

Eventually, Nate was knocked out of the NFL, thanks to a combination of injuries and prudence. The Lions cut him in September 2012. The following January, he was taking courses to prepare for the Medical College Admission Test, then worked as a travel nurse until shortly before entering medical school in 2015.

“I got in five years in the NFL - one was an injury year - the magic number where the benefits are better,” he said. “I also wanted to get as many years as I could without it being a detriment to my health.

“I didn't think it would be a good idea to go to medical school with a lot of head injuries,” he said with a smile.

Still, there were plusses to earning a spot in one of the world's elite pro sports organizations, not the least of which was this: “The people I met, the friendships I made, that was great,” he said.

And the climate of intense rigor could only help prepare him for med school.

“In the NFL and as a medical student, you definitely want to do the best you can,” he said. “In both, you know if you're not doing well in one thing, you need to concentrate on that, which means something else might suffer.

“It's a balancing act. It's competitive.”