CDDR-sponsored study hints at future treatment for autism spectrum disorders

Published on March 02, 2015

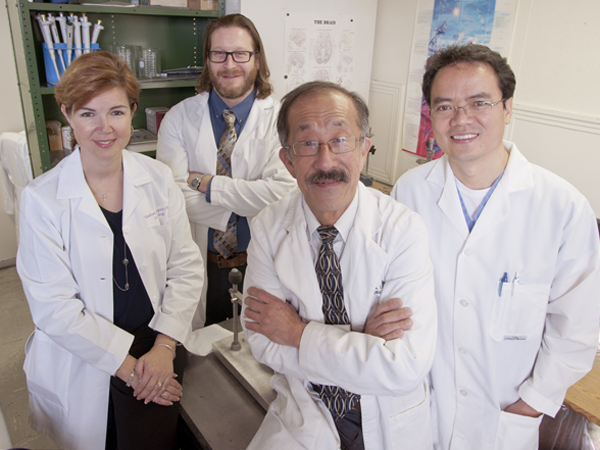

A team of Mississippi and California researchers have managed to prove something scientists have hoped to be true about the brain.

It can be rewired.The research team's findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), could one day translate into an effective treatment for patients with autism spectrum disorders, said the report's co-author, Dr. Rick Lin, professor of neurobiology and anatomical sciences at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

News of the discovery, which builds on work Lin and a group of colleagues have been involved with for some time, coincides with the formation of the Center for Developmental Disorders Research at UMMC. The acronym CDDR is pronounced like the tree.

"One of the biggest goals of CDDR is to build an army of physician-scientists and basic scientists focused on developmental research," said Dr. Ian Paul, professor of psychiatry and human behavior and CDDR co-founder. "Because we're not going to bring them in from elsewhere, Mississippi has a tough time recruiting people at all levels. It always has."

Paul

Paul said CDDR also was established to address the state's track record, which is among the worst for neonatal and infant care in the country.

Studies such as Lin's serve as proof of the need for CDDR, said Paul.

The findings from Lin's study, for now, are limited to the test subjects - rats. But the results have proven that these animals' brains can be rewired via intense auditory behavioral training, said Lin.

The intricacies of a brain's wiring remain one of the largest puzzles before scientific researchers who have taken years to solve pieces of the complex mechanism. Yet for every question answered, more seem to appear.

So when the UMMC team, working with scientists at the University of California in San Francisco, discovered the potential reset button, the discovery immediately drew questions of what the findings could mean for the future of autism treatments and, it is hoped, better outcomes.

The particular test subjects were injected with a drug that stimulated serotonin receptors, which in turn induced autistic-like behaviors in the young rats, said Lin.

"The rats were just not going to play with one another," Lin said of the test subjects. "Just how a child with autism prefers to play by himself, so were these animals.

"They were also super nervous, and when we would try to excite them with noise, they would just freeze. That's not typical of a rat."

Together with UCSF researcher Dr. Michael Merzenich, the teams subjected the rats with the autistic-like behaviors to a specific set of tones and clicks that had proven in other experiments to drive plasticity, the process by which the brain changes over time, Paul said.

"In your brain, there are cells connected to the nerves running to the ear that respond very precisely to one particular frequency of sound," he said, adding that the test rats were hearing the sounds at distorted frequencies and therefore not having typical responses. "It's almost as if you hear the world completely muffled.

"It turns out autistic kids can have some of the same problems."

The study focused on the plasticity of the brain, asking if these neurological distortions could be reversed - or overcome - via simple forms of brain training, said Merzenich.

"Animals whose brains had been altered in all the above ways by administration (shortly after birth) of an antidepressant drug were trained in a relatively simple but strongly behaviorally engaging listening task," said Merzenich. "Through this training, animals progressively sharpened their abilities to distinguish fine differences between the sounds that they heard."

In a nutshell, said Merzenich: This training had a dramatic impact on all of the autism-like neurological distortions in their brains.

Lin said the behavior training took about two months, and the results were only prevalent in the male test subjects.

"We know in the general population, there's about four times more boys being diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders than girls," he said. "We don't understand why there are sex differences."

The implications for treatment of autism spectrum disorders in humans are present, though researchers caution that could be some time away.

Lin said the intense nature of the training, which occurred every day for many hours during two months, would be the equivalent of two years or so in a human child's life.

All the involved parties agree the findings are a sign of hope for the future.

"The most amazing part, the reason why this paper is so important and can bring hope to families with autistic children, is this is the first study to ever show on the animal side that the brain can be rewired after intensive auditory training," said Lin. "What might be our future strategy on the human side is that we need to find a very supportive system to enforce these lessons with the kids. But these have to be intense interventions.

"We have to push much harder."