Bodies of Knowledge: 6 students explore life through death

Published on January 15, 2015

DREAMING

Let’s start with the dreams.

In one of hers, Rachel Sharp sees her brother getting hurt playing football. She can see through him, to the damaged artery inside. She’s seen one like it before, a real one, inside the body of a man whose name she doesn’t know.

There’s another one: She and Colton Lee and Kate Garner are in Walmart when they spot an elderly man; he has symptoms of diabetes mellitus, a disease that attacks the kidneys. They’ve seen something like this, too, in the body of the man whose name they don’t know: traces of renal disease.

Dreams for Kate had been rare – until medical school. Now, she dreams almost every night.

For about 16 weeks, Rachel, Kate and Colton work closely with three other students: Cathy Chen, Brent Necaise and Kim Zachow. These are the first-year medical students at Table 25.

“The table is small and the work is hard,” says Cathy Chen. “If you don’t get along and work together, it’d probably be miserable.” These students don’t have that problem.

They even allow me to shadow them throughout the life-changing experience, to get a peek inside their exclusive club: Gross Anatomy.

So I dream, too. The outsider who only came to observe, who swore he wouldn’t get too close. But, eyes shut, in bed, I see human bones and distorted faces in the dark.

The dreams begin not long after The Talk, which comes on Day One: Gross Anatomy is the day medical school starts, says Dr. Allan Sinning, director of the course and professor of neurobiology and anatomical sciences.

During their essential rite of passage, students learn the arteries. They learn signs of disease. They don’t learn the names of the men and women on the tables, but discover some of their secrets.

They see things most people will never see, or want to – on the tables and in their dreams.

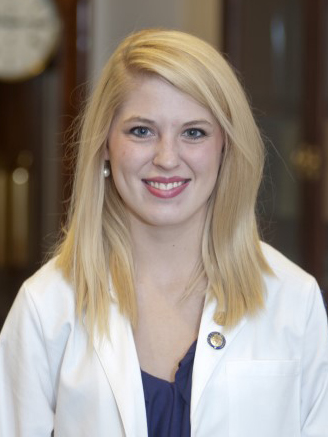

RACHEL

Sharp

It is one of Rachel Sharp’s worst fears: She’ll recognize “the person under the sheet.”

Playing with a Dr. Barbie as a kid growing up in Sturgis did not prepare her for medical school. Taking UMMC’s six-week pre-matriculation program in the summer did.

She was trying to get emotionally adjusted, she says, before the grade counted in the fall.

She saw her first cadavers that summer. “Seeing dirt under their fingernails,” she says, “that’s what gets me.”

This fall, prepping for the practical exam, she enters the lab one weekend to study all the cadavers. She finds a woman with bright, pink fingernails. The journal by the table says she died of senile dementia.

Rachel knows families find it hard to care for relatives with dementia. Many are put in nursing homes. “It’s a very sad disease.”

Rachel thinks about this woman, picturing a daughter or granddaughter who visited her to paint her fingernails on one of the last days of life.

“This lady must have been loved,” Rachel thinks. Remembering this, always, is how she copes.

EXPLORING

Ian Taylor scrutinizes a bone kit.

There is a debate over the use of cadavers for dissection.

After all, there are medical scans and imaging, such as MRIs; simulated dissection via computer programs; specialized mannequins. Couldn’t students learn Gross Anatomy just as well with those tools?

At UMMC, the belief is that a student should explore the geography of the human body through sight and touch, as a doctor would examine his or her patient. This journey cannot be duplicated.

The difference between studying pristine textbook illustrations and holding a human heart in your hand is the difference between watching a baseball game on TV and playing catcher in one.

On the first day of dissection, instructor Dr. Ryan Darling explains it to me. “When they touch this,” he says, pointing to a cadaver’s chest, “we like them to touch this,” he says, tapping his own torso.

“We want them to realize that this tissue is this tissue,” he says, meaning the cadaver’s and the students’.

“Anatomy is all about relationships: functional, relationships, spatial relationships. All you’re doing is relating,” he tells the students.

Later, it occurs to me that, as they take apart the body with their hands, they’re putting it back together in their heads. This is how they learn.

I turn to Jessica Jenkins of Jackson, a student at Table 16 who has taken a Gross Anatomy course before. She agrees that hands-on dissection is the best way to learn.

“As it gets tougher,” she says, “you learn more about yourself.”

I learn this about myself: I will never get used to the smell.

Katie Howell, left, heeds an explanation from Gabrielle Rattliffe.

Decades after medical school, doctors still talk about it: formalin and flesh. It irritates the nose and can burn the back of the throat. A chemical reek mixed with the odor of wet dog, it can’t be washed from your memory.

If the Dementors from Harry Potter have a smell, it should be this.

An ex-newspaper reporter, I’ve seen one or two bodies of people who died violently. Still, for me to endure the sight and smell of a cadaver for the first time requires serious negotiations with my own organs.

I tell my brain that being dissected in the lab is more useful than decaying in the grave. I tell my stomach and nose: “Man up.”

Across the lab, students are pushing handles on the metallic bins. Lids open and the cadavers rise. I look around at the students, many of whom are seeing extra-funeral death for the first time. Some, as they remove the white sheets from the bodies, look as if they’re about to open Christmas presents.

Others seem to be praying with their eyes open. On her first time in Gross Anatomy, Kim Zachow was hoping she wouldn’t faint.

KIM

Zachow

Even at funerals, she avoids looking at the bodies – mostly because she wants to remember the people when they were alive.

Kim Zachow took her first course in Gross Anatomy at Mississippi College, where she had pursued her Master’s in Biological Medical Sciences a year earlier. That was her first close look at a dead body.

She endured, but the student next to her almost passed out. And the lab group at MC chose Kim to make the first cut.

In the lab at UMMC, as she was at MC, she is mindful that the body has a family, and that all the people lying on the tables had made the decision to give their bodies to science. She remembers this as she makes the cut.

“It means a lot,” she says. “It’s not something I’m sure I could do.”

There are six to each table. It’s tricky, trying to introduce yourself to six people who are dissecting a body. They’re pretty much focused on that.

Asking them to tolerate me throughout the long course didn’t seem fair. I don’t enter the lab with a good strategy for winning acceptance – unless you call loitering by the nearest exit a strategy.

Anyway, it works. Mercifully, the students nearest the door adopt me, and over time I come to feel less like a stray cat and more like an honorary member of their team: Table 25.

Still, the sights in the lab, which is newly-renovated and brightly lit, can overwhelm me if I let down my guard.

At times, I suspect, it’s the same for them. They cope by quoting lines from Mean Girls or from a video they’ve shared.

They’re particularly fond of catchword from a Wife Swap YouTube clip.

“This is so dark-sided,” someone will say. They laugh, and go back to work.

They’re tough alright. But not invulnerable.

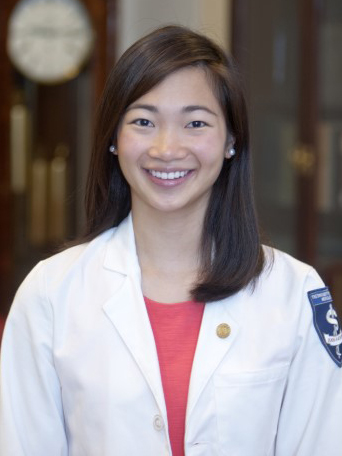

CATHY

Chen

It was difficult for Cathy Chen to look at him at first – a pale-yellow figure that seems as rigid as marble, except for his white hair.

One of the students at Table 25, she is 23. The man on her table was 91. Cathy went to Princeton. He carried mail for a living.

This body, separated from the spirit, makes her “uncomfortable.”

“I guess it’s just because I feel so connected with, and alive in, my body right now,” she says later. “I’m sure he, too, felt very connected to his body when he was alive.”

First, they dissect his back. Place the cadaver in prone position, make the skin incision, reflect the skin off the back, Dr. Adel Maklad had instructed them.

“The whole idea is to divide the skin into … convenient flaps,” Maklad told the class.

Everything will be disconnected now.

Like Cathy, most of the 150 or so students are in their 20s, their eyes alert behind their safety eyeglasses and above a smattering of surgical masks. Most of the 30 or so men and women they work on died much older.

That the students might identify with their “first patients” seems unlikely to me, and, in fact, unwise. But sometimes, they can’t help it: Weeks into the course there will be a moment when Cathy backs away from the body and gasps.

Fluids had dripped from the area around the cadaver’s ACL, where signs of osteoporosis lurk.

In college, Cathy injured her knee in a pickup basketball game. Now, when she examines the knee of the man on the table, it’s almost as if she’s looking at her own.

COMPARING

Vy Mai, left, has a question for Dr. Allan Sinning.

“Always think of an onion – the different layers,” Darling says, standing beside some students working on the upper back.

Later, when the arteries, veins and muscles of the arm are laid open, I will think, not of an onion, but of exposed wiring.

“Follow the striations of the muscle,” Darling continues. “You see how thick that white line is – that’s what you want to look for when you start looking for the nerves.”

He shows them how to stabilize their scissors, pressing his forefinger against the bottom of the blades, where they intersect.

One student’s face colors slightly. She says she once had trouble dissecting a pig. Darling tells her to take a break.

She says, “Yeah, I don’t want to be that student. All that paperwork.”

No one can know for sure how they’ll react the first time.

“They ask you if you’ll be OK with this,” Colton Lee says. “You CAN’T say no.”

COLTON

Lee

It’s like driving a car for the first time, he says. In Gross Anatomy, the keys are forceps, scissors and scalpels.

Colton Lee’s original Day One arrived during a pre-med course at William Carey University, where he dissected his first cadaver. “An intense moment of self-doubt.”

As with the other students at Table 25, the inherent grossness of Gross Anatomy is not the problem for him. In fact, one day he shows me his “favorite” muscle, which controls the wrist.

“Because it’s square,” he explains his preference to Dr. Marianne Conway. “I’m weird.”

Brought up in Poplarville, he worked for two years in Central Sterile/Surgery in a Hattiesburg hospital. He had held surgical instruments before. This is different.

“This was someone’s dad, brother, son or friend,” he says. “He lived and laughed exactly like I do, and now he doesn’t do any of those things and I’m cutting him open.”

Each table is equipped with a journal. On the first page is a brief bio with no name. That’s how the students at Table 25 know they’re dissecting a former employee of the U.S. Postal Service.

When Colton is dissecting, he can imagine himself as a kid, waiting for the man who brings the mail.

DISCOVERING

Jessica Arnold scans a textbook to nail down the day's dissection assignment.

The cadaver journals serve another purpose.

At each table, the students are divided into two sub-groups of three. They make alternate appearances in the lab on dissection days. For the most part, the sub-groups are together in lab only for the dissection “hand-off” and for quizzes.

The discoveries and observations one sub-group records in the journals keep the other up to speed: scars, signs of a mastectomy, pacemaker, injection ports, tattoos. They must also record what they accidentally destroy.

At one point, the students at Table 25 note this: sutures in their cadaver’s right shoulder – evidence of surgery.

But, like some other students, they record extra-curricular observations as well: “Dr. Darling’s ponytail is better than mine.” The handwriting is Kate’s.

KATE

Garner

Before the first cut at Table 25, Kate Garner’s nerves tear into her.

She had enjoyed her work as an X-ray technician, but she wanted to do more. That’s why she’s standing here, hovering over her first cadaver. Right here, medical school becomes real.

The man’s fingernails and hair are also real; they remind her that this is a person. For the most part, the face will stay covered under a blue cloth until it’s dissected – out of respect, and to keep it from drying out.

But, on the first day, it’s Kate who lifts the blue cloth to take a peek. More reality.

Over the coming weeks, there will be days when she’d rather do anything than dissect. But she’s always grateful to be here. Her friends are glad she’s here too.

BRENT

Necaise

Keep a professional attitude toward the cadavers and each other. Work as a team. Take no photos in the lab.

“You would not take a picture of your patient without their permission and put it on Facebook,” Sinning tells the students.

These are the rules.

Students are graded on written tests, practical exams in the lab and according to the quality of their dissections. Dissecting is a strong point for the students at Table 25.

Under questioning from their instructors on quiz days, they encourage each other. They exchange high-fives.

Brent Necaise has probably seen more of life than the others at Table 25. He’s the oldest member of the team by nine years. But he can’t imagine medical school without them.

At 34, he has been, among other things, a bank manager and a near-priest.

About a year ago, Necaise started working on a biology degree; after shadowing a doctor, he decided he wanted to be one.

In preparing for the ministry, he had encountered the faces of death and grief, but, as medical school approached, he grew anxious.

He remembered what it was like to work in the bank, dealing with all that cash, treating it respectfully and responsibly. But there were times, as he struggled to pay his bills, when he made himself forget the money was real.

This technique of disassociation, he believes, will serve him well as he dissects a human being. He tells himself: The body is not the person.

WONDERING

Colton, Kim and Brent inspect the heart

There is a heart in my hand. This is a first for me.

I’m holding it at the invitation of Kim Zachow; I do it to be polite, and to prove to myself that I can.

It’s a month into the course. The students have worked through the vertebral canal, spinal cord, various nerves and vessels, the pectoral region, flexor forearm, palm of the hand, joints of the upper limb and more.

At one point, Dr. Yue Lu gives me an inventory: 140 nerves, 120 blood vessels, 210 muscles – 80 in the head and neck alone.

Today, it’s the lungs and heart. Kim, Cathy and Brent use an electric saw with a curved blade about two inches wide. Slicing through the ribs and sternum, it sounds like a dental drill.

Bone dust collects in the air. A drop of sweat clings to end of Brent’s nose.

Kim is holding the saw when it drops through the chest. “I’ve got it,” she says. “I’ve got it.” Pulled from the body, the ribs resemble large butterfly wings.

Exposed, the lungs are light beige, spotted and slightly veined. Pressing them with her gloved hand, Cathy says, “Whoa. They feel like dough.”

When they remove the heart, Kim points out the valves to me. “Isn’t that neat?” she says.

That’s when she asks me if I want to hold it. I put on a glove, cradle it in my hand. If this had happened a few weeks earlier, maybe I would have thought of the man it once belonged to. How it beat a little faster the first time he met his future wife.

Instead, I see a machine. A beautiful pump.

What’s happening to me? I wonder.

SETTLING

Dr. Adel Maklad (second from left) quizzes the students at Table 25: counterclockwise, from left, Brent Necaise, Kate Garner, Kim Zachow, Colton Lee and Rachel Sharp.

Sometimes, in class, Colton thinks, “Holy crap, I’m going to be a doctor.”

“Then someone in class says something and you think, ‘Holy crap, he’s going to be a doctor.’”

Maybe the pressures of medical school can bring out the worst in some people. But, with these six students, it seems to bring out the best.

They give each other compliments, when they aren’t giving each other hell – a friendly, teasing give-and-take, moments of normal, sane human contact that, at the least, help settle my nerves in this unsettling place.

Kate: “You can’t get a tattoo. You’re going to be a doctor, Colton.”

Colton: “I’m not going to be a naked doctor.”

ENDURING

Ann Marie Mercier, left, and Kristen Wilson borrow a human skeleton model to study the anatomy of the shoulder.

October 15: It looks like a MASH unit has exploded.

From behind her mask, Kim says to me, “It’s a very peculiar day.”

Pelvis and perineum dissection day.

Dr. Andrew Notebaert is Table 25’s instructor today. He seems impervious to the sights. He could be picking flowers in the park.

But, to me the lab reminds me of a painting I’ve seen in a book, “Garden of Earthly Delights.” It is a painting of hell.

In the lab, students stand outside a room with a large sink, holding the leg quarters they’ve removed with saws.

Overheard: “Never in a million years did I think I’d be standing in line waiting to wash a cadaver leg.”

Across the lab, the jokes rarely stop. This is how the students manage.

At Table 25, where Brent, Cathy and Kim are working, I say, “You must want to be doctors really bad.”

Brent says, “That’s what we keep telling ourselves.”

REVEALING

At this stage of dissection, the students at Table 25 keep their cadaver's face covered with a blue cloth.

It’s November now. Three months of dissecting have dehumanized the bodies. Or so it seems.

But when the blue cloth comes off at Table 25, Kim makes the first cut and winces.

“I feel the scruff of his beard,” she says.

Try to cut into that and not think about the person who grew it.

No doubt, the students will handle it, as they have everything else; but how?

Next door, at Table 14, Ian Taylor and Nicholas Boullard are discussing Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.

They’re trying to remember the name of a fantasy segment they used to watch as kids. Brent overhears them.

“The Land of Make Believe,” he calls out.

Ian and Nicholas smile. “That’s it.”

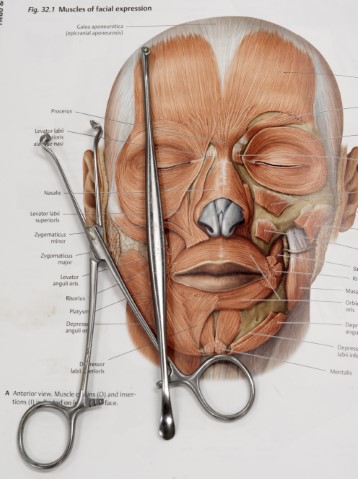

LEAVING

Fig. 32.1 Muscles of facial expression

It’s heavier than it looks, about eight pounds. Kim has let me hold it in my gloved hand.

The students used a saw, scalpel, mallet and chisel to get to it. “It’s amazing,” Kim says.

At the back of the room, Jeremy Stocks is examining the one pulled from the skull at Table 7. Soundlessly, he mouths one word: “Beautiful.”

In March, the students will dissect their specimens, but, until then, each one is bagged up, preserved and stored.

Before theirs is put away, Cathy, Brent and Kim place their hands on the brain from the man at Table 25.

“Let’s say goodbye,” Kim says.

WAKING

First-year medical students, from left, Kate Garner, Colton Lee, Cathy Chen, Kim Zachow and Brent Necaise join their fellow classmates in the coat-burning ritual, an annual rite of passage for M1s celebrating the end of Gross Anatomy by chucking their lab coats into a roaring fire. The ceremony was part of a semester-ending party held Dec. 12 at McClain Lodge in Rankin County. These five students, along with Rachel Sharp, worked together at the lab’s Table 25.

Outside the lab, life went on for the students. And death. Brent buried his grandmother before Thanksgiving.

One student was the victim of what appeared to be attempted burglary. Over the course of four months, a lot more must have happened to them that I’ll never know about.

But, inside the lab, I got to know them. To paraphrase a sports cliché, Gross Anatomy, and medical school in general, doesn’t build character, but can reveal it.

A lot of character was on display at Table 25. Many of the things I saw and heard, I’ll always remember. Certainly, I’ll never forget what Rachel said to me one day as they put away the body – a routine that requires spraying it with a solution to keep it from drying out.

“I kept thinking,” Rachel says, “‘don’t get it in his eyes.’”

Long before this day, Colton had admitted that he feels possessive of the man on the table.

I’ve come to feel the same way. Maybe it happens the day Rachel asks me if I’d like to help.

While she scrapes away fascia in the chest cavity, I use forceps to hold the trachea out of her way. It strikes me that I’ve taken this man, in a literal and profound way, by the throat.

This man, whose good heart I had held, must have been filled with trust. And self-respect.

He must have imagined what would be done to his body after death. But he wanted to remain useful.

This was his last job on earth, and I’ve had the privilege of watching him work.

“We’re glad you’re here, Mr. Gary,” Colton says to me one day. “You’re as much a part of our group as our cadaver.”

I take this as the highest compliment.

LAB REPORT:

Located on the seventh floor of the North Wing, the Gross Anatomy lab underwent its first-ever renovation, and the medical school class of 2018, along with a couple of graduate students, was the first to experience the benefits of the transformation.

The work involved putting in a new air-handling system that replaces the air every four minutes, improving the lighting, installing new dry wall and flooring, replacing two storage rooms (for chemicals and bones) with one, giving the ceiling a facelift that included covering exposed pipes, and placing a drain tank in the washroom. Part of the transformation was in progress at press time: placing monitors at tables to provide access to an online dissection Website and mounting a portable camera system for demonstrations at cadaver tables.

Faculty and administration:

Dr. Michael Lehman, professor and chair, Department of

Neurobiology and Anatomical Sciences

Dr. James “J.C.” Lynch, professor and vice chair

Dr. Allan Sinning, professor and Gross Anatomy course director

Dr. Ranjan Batra, associate professor

Dr. Marianne Conway, assistant professor

Dr. Ryan Darling, post-doctoral fellow

Dr. Yuegen “Jordan” Lu, assistant professor

Dr. Adel Maklad, associate professor

Dr. Andrew Notebaert, assistant professor

Dr. Lyssa Weatherly, tutor, resident

Kenneth Sullivan, anatomical material specialist