Best Case Scenario: Retiring professor found sense of place at UMMC

Published on January 15, 2015

Before Dr. Steve Case joined the admissions committee in the School of Medicine, his predecessors were already trying to turn the clock ahead.

But Case and his committee made it spin.

The lasting impact Case has made on the School of Medicine began when he and his colleagues began asking themselves certain questions, such as: “Is a student’s head for medicine more important than the student’s heart?”

The answer is found in the balance and blend of backgrounds that mark the medical school classes since Case began serving in admissions 14 years ago.

Now, as his career comes to an end, a great part of his legacy will be this: He helped students find something he had once longed for: a sense of place.

On Long Island, N.Y., where he grew up and played baseball and where the high school football team held its games on Saturdays, he took up the trombone.

He liked music and his arms were long.

But, on game days, instead of playing with the band on the football field, he worked with his father in the cemetery.

The man was actually Case’s stepfather, and he’d been a cop before he got a job setting place cards for the dead.

“I spent a lot of Saturdays and holidays putting in gravestones with him,” Case said.

“What I admired about my father was his worth ethic. What I didn’t admire about him was that he never came to one of my baseball games. We never took a family vacation.”

The rest of the family included one sister and a mom who worked, in effect, as a nurses’ assistant. She had re-married after her divorce.

Much of the adult attention Case received came from his uncles, who pitched in when he was 8 and sent him to 4-H camp, a place he retreated to every summer until he was in his 20s.

“I was looking for a way to stay out of my house.”

By the time he was 12 or 13, he was a counselor at camp, where he would learn how to frame cabins and do plumbing and electrical work and to drive a dump truck.

Camp nurtured him and gave him a sense of responsibility, accomplishment and camaraderie. At least for the summer, it was home.

Dr. Nina Washington

Dr. Nina Washington was with Steve Case the day he ran out of gas.

An undergraduate at the time, she had been accepted to several medical schools, but she’s from Jackson – one reason she chose UMMC.

Another was Case – the man who drove to New Orleans to recruit her and a fellow Xavier University undergrad, Rozell Chapman.

“The three of us were on the way back to Jackson, and Dr. Case and I were just yakking,” Washington said, “and on I-55 the van suddenly stops and we’re stranded outside Terry, so we had to call Rozell’s dad.

“That shows how open and causal and charming Dr. Case is – that we could be talking away, not realizing we didn’t have enough gas in the tank.”

But what he really did to draw her to UMMC was this, she said: “He believed that, to be a physician, you didn’t have to have a 4.0 or a high score on the MCAT. He believed you didn’t have to look a certain way.

“He looked for the well-rounded person. He saw beyond the numbers.”

Dr. Rozell Chapman is now a pediatrician in Lexington. Washington is an assistant professor of pediatrics at UMMC.

Case was one of many at the Medical Center who wanted them to succeed, she said. “From the beginning, this was home.”

They came from Pennsylvania to California in a bug – a yellow, ’71 Volkswagen – pulling a U-Haul trailer that held about all they owned: wedding gifts.

Case and his new wife Gay slept in an Army pup tent by night and saw America by day, traveling across the country so she could work in California as a nurse and he could earn his Ph.D. at USC on a tuition-free fellowship in cellular and molecular biology.

They arrived in Los Angeles with $100, cash. “We were on an adventure,” Case said.

Searching through a medical school yearbook, Dr. Steve Case, left, dredges up some memories with Dr. Lyssa Weatherly, an internal medicine resident, and Eric McDonald, a fourth-year medical student.

Their adventure began where they had met, at Pennsylvania Military College – now Widener University – in Chester, Pa., where Case was a student. Gay, enrolled in the Hahnemann Hospital School of Nursing, lived nearby in Ridley Park.

In 1965, using student loans and some money from his parents, Case became the first in his family to go to college; he played trombone in the PMC band.

“I got to go to football games,” he said.

But music didn’t interest him the way science and numbers did. Apparently, his aptitude made an impression on “the professor I hated the most.”

“My senior year in college, for some reason, he looked out for me,” Case said.

With his professor’s connections, Case was able to pursue his master’s at Wilkes College (now a university) in northeast Pennsylvania, paying his tuition with a teaching assistantship in chemistry, “which I also hated,” he said.

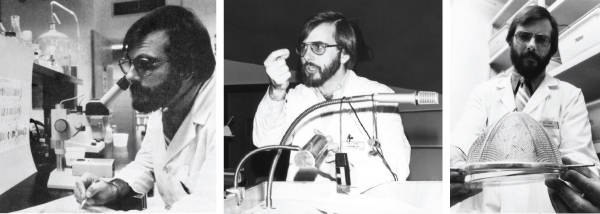

(Left): Dr. Steve Case in his biochemistry lab, in the 1980s. (Middle): Case lectures first-year medical students in biochemistry class, during the early 1980s. (Right): In a photo taken in the early 1980s, Case examines a strainer containing adult midges, which were raised in his biochemistry lab to study genes that encode proteins used by aquatic midge larvae to form underwater silk fibers.

Later, he switched to biology, to try and satisfy his curiosity about fruit flies and genetics, which fascinated him. As did “that nursing student down in Philly.”

He and Gay began dating again.

“She gave me direction and focus,” Case said. “Once we became a pair, I had a purpose. Until then, I hadn’t any.”

Soon, together, they would also have a home.

Dr. LouAnn Woodward, Class of ’91, was an M1 when she noticed the “tall, scary man.”

That was her original impression of Case – a notion that soon vanished under the power of his charm.

“He remembers students’ names,” she said. “He remembers details of conversations with them. He makes them feel comfortable.”

This was Case during his career as a researcher and molecular biology instructor in the late 1980s.

Until his retirement, he reported to his former student: Woodward, UMMC’s associate vice chancellor for health affairs and vice dean of the School of Medicine.

He did so as associate dean for medical school admissions, a position he held since 2000. He did so, apparently, without worrying that he’d be second-guessed.

“He’s so good, you just stay out of his way and don’t mess it up,” Woodward said.

Each year, the admissions committee accepts 145 hopefuls, interviews more than 200, and is lobbied by more than 300.

“You call him up about a certain applicant and he knows just who you’re talking about,” said Dr. James Keeton, vice chancellor for health affairs and dean of the medical school.

“It’s phenomenal. There could not have been a more perfect person for that job.”

In the world of medical school admissions, Case built a national model.

His committee is known for overseeing a series of mini-interviews, calling it “speed dating.”

It’s known for building relationships with other colleges and universities, particularly those that are historically African-American.

In the pre-Case era, 44 percent of African-American students accepted to the School of Medicine chose to enroll here. Today, it’s 83 percent. Before Case, 55 percent who applied were accepted; it’s 94 percent today.

The committee is known for its “holistic review” – weighing not only the prospects’ academics, but also their character and compassion, to ensure that Mississippi’s doctors look like its patients.

How is that working? Medical school students come here with GPAs and entrance exam scores below the national average; by graduation, their test scores have shot above the norm.

Because of the admission committee’s work, more women and minorities are practicing medicine in Mississippi, Keeton said. “The impact is dramatic.”

But, as Case will tell you, diversity is not about just gender and race. It’s also about people like Eric McDonald, a husband and soon-to-be father of six who worked 10 years as a firefighter before taking a stab at medical school.

“If Dr. Case didn’t have the ability to look outside the box, to look at someone like me, I wouldn’t be here,” said McDonald, a fourth-year medical student.

Recently, McDonald dropped by Case’s office, where the two exchanged a bear hug. As if one of them had left and come back home.

UMMC was not on his A-list.

“I had a long, hard discussion with Gay,” Case said. “Los Angeles, Fort Knox, Stockholm, Yale. And now Mississippi?”

The road to his Ph.D. and beyond – actually, the road, ocean and airway – led from California to Kentucky, where he learned to “shoot, drive and take apart tanks” in the Army Reserve, and then to Sweden, where the National Institutes of Health (NIH) paid for his post-doctorate fellowship in histology.

It led back to the States, to Yale University, where he earned a second fellowship, in the Department of Biology. Now, he was ready for a real job.

He wanted to do research, preferably in a medical school. He interviewed at UMMC – to “rehearse.”

But UMMC “kept rising to the top of my list,” he said. The new chair of biochemistry was building the department, equipment was state-of-the-art; he’d enjoy “maximum lab time.”

In Mississippi, the cost of living was as friendly and pleasant as the people.

“It was a combination no other school could touch,” Case said. “Gay said, ‘Let’s give it a try.’ ”

The tryout lasted 35 years, beginning under the vice chancellorship of the late Dr. Wallace Conerly, Case said.

“I once told him, ‘You gave me the chance to have two different careers and keep the same parking space.’ ”

Case came here, with an NIH grant, as a researcher in recombinant DNA and chair of what is now called the institutional biosafety committee. But, when it came time for a grant renewal, there was no talk of leaving the Medical Center or Mississippi in the Case household.

“We had found everything we came looking for,” Case said.

Dr. Steve Case, back row, center, is surrounded by his family during a reception at UMMC honoring his years of service. With him are, back row, from left, his son Chad Erik Case, wife Gay Lynn Case, daughter-in-law Mary Margaret Case and granddaughter Catherine Bryan “Kitty” Case; front row, from left: granddaughters Audrey Davis “Dee” Case and Mary McLauren “Macky” Case.

They brought up two children, Chad and Jill. Because of their parents’ work schedules, they spent much of their early lives at the Medical Center with a dad who picked them up from daycare and took them with him to the lab, where they fell asleep on his desk. Then he’d take them home and put them to bed.

He worked a lot of weekends in the lab, but he took time out for his kids. He even attended the away games of his son’s high school baseball team and daughter’s high school basketball team, although he doesn’t remember her getting off the bench the first season, he said.

“Later, she told us the parents of some of the starters never showed up.”

Case believed that was no way to make a home.

Lyssa Taylor had a sister who “broke a boy’s heart.”

Normally, this would not be big news – unless she, that is, Lyssa, was trying to get into medical school, which she was, and unless the boy was Dr. Steve Case’s son, which he was.

“I was terrified that Dr. Case was not going to like me because of my sister,” she said. “I was so nervous during the interview that I finally brought it up. He acted as if he hadn’t even made the connection.

“I say that to show that he has tons of integrity, to show how impartial he is, which is hard in his position – people begging to get in medical school.”

Lyssa Taylor did not get in the first time. But it wasn’t her sister’s fault. It was, she believes, because of her MCAT score, combined with her admissions essay, a “cookie-cutter” work she wrote with her head.

On her second try, she wrote from her heart. Today, whenever she visits Case, it’s as Dr. Lyssa Weatherly, third-year resident in internal medicine, and one of those success stories he might have never helped write if he had left UMMC. Which he almost did.

After 20 years as a “lab jock,” he said, “the thrill was gone.” He might have been, too, if the departing chair of admissions, Dr. Virginia Read, hadn’t encouraged him to give her job a try.

“It was an opportunity to give back to the institution. Dr. Conerly gave me two years to try it out. I found out I had a passion for it,” Case said.

He had a passion for finding the “right students” to fulfill the Medical Center’s mission. It put the thrill back in his work. He enjoyed thrilling the students as well.

“There was an emergency room tech working here who had applied to medical school,” he said. “So I got on a gurney and hid under a sheet in the hospital hallway. A nurse, who was in on the plot, reamed him out for leaving a corpse on the floor.”

The ER tech was mortified – especially when the corpse heaved a big sigh and sat up.

“I had his acceptance letter on my chest,” Case said.

Even if Case hadn’t found a new career at UMMC, he said, he and his family would not have left the state that will always be home.

He has a dream in which he’s playing golf.

His own dad had played, he said. “He had a beautiful swing.”

The difference is Case plays the game with his son and youngest granddaughter. It’s a dream he expects will come true many times after Dec. 31, 2014 his official retirement date, in his and Gay’s new place in Oxford.

That’s 60 miles closer to West Point, where his son and his family have made their home.